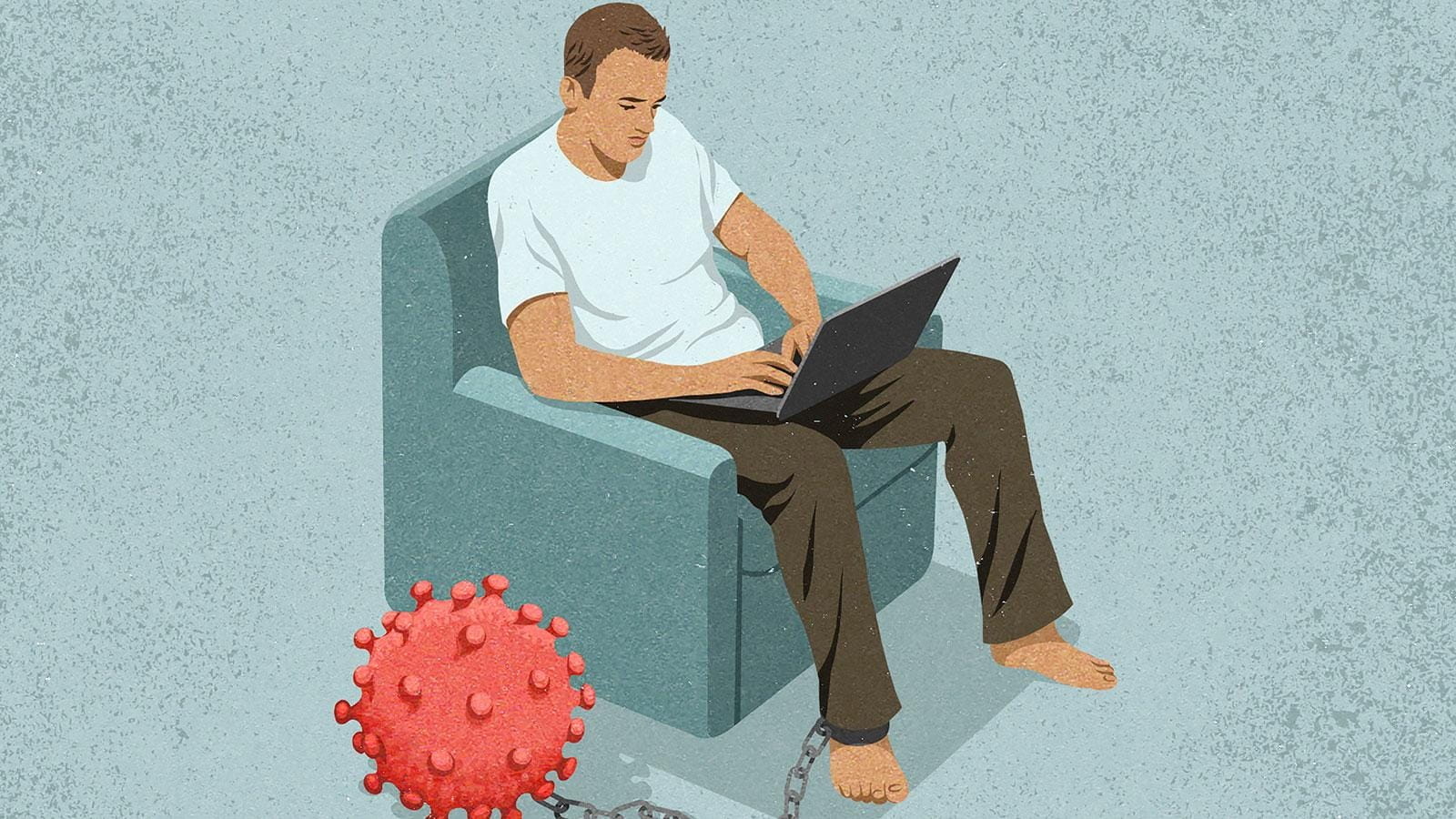

As the move towards flexible working accelerates, Elizabeth Ward-Booth and Anthony Crewe reconsider the definition of permanent establishments in the light of increased remote working.

A permanent establishment (PE) can be created by having a fixed place of business. Traditionally, these were offices or other premises. However, in today’s digital economy, working patterns have evolved. Many sectors operate from any premises or place in the world. Senior individuals work from home or hotel rooms. As businesses become more mobile, the potential to create a PE must be considered.

International and domestic guidance has been evolving to reflect this. For example, the commentary on the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Model Tax Convention contains analysis on whether a home office constitutes a PE.

COVID-19 has rapidly accelerated the move toward flexible working, creating a potential increase in PEs. Further guidance from both the OECD and HMRC has been published in response to the pandemic.

Developments prior to COVID-19

Before COVID-19 struck, the Danish Tax Council (DTC) was approached by a German company with an employee working from home in Denmark on a six-month contract. The company sought a binding ruling on whether it had created a PE in Denmark (see SKM2020.208.SR). The decision considered some issues relevant to evaluating PE risk and home working and centred around three key points that must be present for a PE to exist:

- a place of business;

- that is fixed; and

- it must be a location where business activities are carried out.

The DTC found that the employee’s office was not ‘irregular’, the employee was building a Danish marketplace for the German company (implying continued activity in Denmark) and the activities performed were core to the German business. The DTC concluded that a German company had created a PE in Denmark.

The OECD guidance says the fact that part of a business is carried on within an individual’s home office does not automatically mean there is a PE. However, as demonstrated by the Danish case above, the facts and circumstances of each individual case should be analysed.

The OECD suggests that intermittent or incidental use of a home will not put it at the disposal of the business. However, it indicates that a PE may exist if a home is used for business activities and it is clear that the employee is required to use it for business (for example, where a business has not provided an office where one is needed).

Most employees reside in territories where their employer has one or more places of business where employees can work, so the question of whether a home is at the disposal of an enterprise has rarely been an issue prior to the pandemic and travel restrictions. Furthermore, activities carried on at a home will often be auxiliary and therefore fall outside the definition of a PE in the OECD Model Tax Convention.

The OECD guidance notes that where a place of business was designed to be used for a short period, most countries consider it would not constitute a PE. But if maintained for a longer period (probably over six months), it can become a fixed place of business.

Activities are not normally preparatory or auxiliary where the activity is a core function of the business. Not all territories interpret the OECD guidance in the same way as the DTC; some countries focus more on factors such as whether the employee is required to work from home rather than whether the activities are core.

The UK’s pandemic response

The UK imposed a national lockdown on 23 March 2020, requiring UK-based employees to work from home wherever possible. A similar approach was followed in the lockdown at the start of 2021.

Following the temporary easing of the first lockdown, many employees continued to work from home. This may continue throughout 2021 and beyond. Circumstances vary by sector and by employer – activities in some sectors can only be carried out from business premises and some employers may allow employees to work in offices where their home is not suitable for working.

The UK’s Office for National Statistics found that 49.2% of the UK workforce was working from home during April 2020 as a result of social distancing. If individuals were working outside the UK, either because of travel restrictions or by personal choice, their UK employers needed to consider whether overseas PEs were created.

Where a PE is created, this could trigger other overseas tax obligations such as tax filing, payment and documentation requirements and the need for appropriate transfer pricing arrangements. Conversely, overseas enterprises allowing employees who are UK nationals normally stationed abroad to work from their homes in the UK may have resulted in UK PE issues and related obligations.

Double taxation

As the risk of creating a PE increases, businesses may need to attribute profits to such newly created PEs. For trapped employees of UK companies who create an overseas PE, the country in which they are working would normally have taxing rights on the profits earned there and the UK may be obliged to relieve the company of double taxation under the relevant double tax agreement.

The UK has a minimum foreign tax rule which requires credit for foreign tax to be given only after all relevant claims to reduce foreign tax have been made. This means taxpayers may need to challenge the tax treatment in the overseas country if there are grounds to argue there is no PE. Furthermore, the UK’s corporation tax rate is currently low compared to many other countries and it may not be possible to obtain relief for all foreign tax suffered. Hence, there may be an increased overall tax burden to the business.

If there are new foreign PEs of a UK company, it is worth considering electing into the UK’s foreign branch exemption (FBE) regime so that profits of the foreign PEs are exempt from corporation tax. For example, the FBE regime may be beneficial if the UK head office company has tax losses; it should prevent UK losses from being offset against foreign taxed profits and instead preserve the UK losses for offset against UK profits.

Normally, companies would consider the implications ahead of any planned change. Unfortunately, the rapid course and unforeseen impact of the pandemic prevented forward planning and some companies had to stop their trapped employees working to mitigate the risk of creating overseas tax liabilities.

HMRC and OECD guidance

The OECD considers COVID-19 to be an ‘exceptional circumstance’ and HMRC has stated that it is sympathetic towards situations caused initially by the pandemic. However, it is assumed that HMRC may not be so sympathetic towards situations which have lasted beyond the initial phases of the crisis.

Existing HMRC PE guidance permits some flexibility for businesses facing changes to their business activity and this is therefore applicable to the pandemic. It is understood that non-UK resident companies will not be automatically classed as having a UK PE and UK tax liability. The business activity performed must meet the ‘habitual condition’, as matter of fact and degree. In addition, a UK PE does not necessarily mean that a significant portion of companies’ profits will be subject to UK tax. It is dependent on the circumstances of that corporate entity and must be considered on a case-by-case basis.

The OECD has called for tax administrations to provide guidance on domestic law threshold requirements, domestic filing and other guidance to minimise or eliminate unduly burdensome compliance requirements for taxpayers in the COVID-19 crisis. While this will be dependent on an individual company’s circumstances, it is clear HMRC is committed to minimising unforeseeable administrative and tax costs which arose because of the exceptional circumstances of COVID-19.

What about the future?

Despite OECD commentary and COVID-19 measures acknowledging the impact of the crisis, different tax authorities may take different stances in future. It is important to consider that structural changes relating to employees working more flexibly may create PE issues. Particularly for workers on core business activities, company residence issues may also need to be managed. Even where there is no ‘fixed place of business’ PE, an agency PE might arise where employees are regularly involved in negotiating and concluding business contracts.

Remote working may help maintain business continuity post-Brexit by attracting overseas talent without requiring workers to be UK based. That said, some industry sectors require their providers to be based in the EU/EEA, so having a local subsidiary may be advantageous. This could give rise to UK tax issues if a UK company is treated as moving part of its business to a foreign subsidiary, with a possible UK exit charge based on the market value of the activities treated as transferred.

The ability for businesses to have key people on the ground in more geographic locations may create further opportunities to develop business. However, this is likely to be one of the most common PE risks that could arise in future if companies allow more remote working post-pandemic. Registering a PE or even a local subsidiary suggests a degree of permanence which could attract more local customers in the future. In the past, this may have only been viable for larger corporations with a strong permanent presence in different countries. The greater acceptance of and reliance on technology (accelerated by the pandemic) makes rapid global expansion more accessible to smaller and more digital businesses than previously.

Flexible working may be attractive for businesses whose employees can operate remotely as it saves the employer office costs and could offer a competitive advantage by attracting the best talent, regardless of geographical location. Employees could enjoy greater freedom and flexibility as working from home may:

- help with childcare;

- offer mental health and wellbeing benefits;

- reduce commuting time; and

- provide flexibility concerning where to live (including allowing employees to live with overseas families).

However, certain industries and sectors (for example, manufacturing and regulated sectors) cannot accommodate remote working. Some employees may still prefer and benefit from working in a traditional office environment. Inner-city office space may still be essential for service-provider client meetings.

For companies considering operational changes on a more permanent basis, particularly overseas changes, tax implications and the evolving guidance on PE risks need to be factored into any decision-making from the outset.

About the authors

Elizabeth Ward-Booth, Associate, Tax, and Anthony Crewe, Associate Director, Transfer Pricing, Grant Thornton UK LLP