Rebecca Benneyworth examines the changes that have been forced into the tax system over the past decade and made it more complex than ever

The new relief in Sch 2, Finance Act 2021, which allows a trading loss to be carried back against the previous three years of trading profits, is a welcome measure that tends to be wheeled out regularly in times of financial difficulty. The last time we had such a measure was during the financial crash in 2008/09. But as I have found in looking in depth at this provision and the implications of it, tax is very different in 2021 and, indeed, is considerably more complex as a result of changes made in the past decade.

Over the past 10 years, more and more changes that are essentially ‘not tax’ have been forced into the tax system. Looking at the loss carry back now, the other things that practitioners need to bear in mind when advising clients about the most suitable elections to make are many and diverse.

Is your client married or in a civil partnership where transfer of part of the personal allowance between the couple becomes available or desirable? Are there children in the household? If so, has the high income child benefit charge (HICBC) been an issue? How will the loss elections affect that? These are just the tip of the complexity iceberg that practitioners are having to grapple with if their client’s business has incurred losses during the pandemic.

After years of hard work by the Office of Tax Simplification (OTS), it seems as though we are going backwards. Successive governments park their pet projects in the tax system, adding significant complexity as they go. Far from ‘one in, one out’, which has been the rallying cry of those bent on simplification, we seem to be in a land of ‘three in, one out’ in relation to the personal tax computation and the issues that affect it.

Loss carry back shines a light on complexity

I have described two of the issues to consider above, but it is just worth listing all of the issues I believe will be relevant to those seeking to make a carry back loss claim – issues that are unrelated directly to the claim and consequent relief given. So, brace yourselves for an unhappy list:

- the availability of marriage allowance and the need to put in backdated claims;

- HICBC and the possibility of the liability moving retrospectively to the other partner in the household;

- HICBC where an election has been made to not receive child benefit;

- pensions annual allowance charges levied previously, and whether these were dealt with through ‘scheme pays’

- the impact of loss relief on repayments of student loans;

- the presence of interest relief on residential lettings and the impact of a loss claim on the interest previously relieved;

- whether the taxpayer has prepared their business accounts on a cash basis, which means the new relief is not available to them;

- capital gains tax liabilities, which may be affected by a carry back loss claim as a result of the income reducing;

- tax liabilities now arising on gift aid payments made previously; and

- identifying and capturing separate relief for Class 4 NIC.

Find more details about these issues in TAXguide 14/21 Income tax loss carry back.

Self assessment powers and amounts that are not income

The problem with ‘parking’ things in the tax system that don’t belong there is amply demonstrated in the recent Upper Tribunal decision in Commissioners for HM Revenue & Customs v Jason Wilkes [2021] UKUT 0150 (TCC) released on 30 June.

Mr Wilkes was taxed under PAYE in the relevant years and was not required to complete a self assessment return. Unbeknown to him, he became liable to HICBC in tax years 2014/15 to 2016/17, which was not collected. Mr Wilkes should have notified HMRC (by virtue of s7(3)(c), Taxes Management Act 1970 (TMA 1970)) that he was liable to the charge so that a self assessment return could be issued, but he failed to do so.

On establishing this, HMRC issued a discovery assessment under s29(1)(a), TMA 1970. But the law provides that this is an assessment on “income which ought to have been assessed to income tax”.

The Tribunal ruled that the liability to HICBC is not income that ought to be assessed, in spite of the fact that it does form part of the tax charge for the year. The judgement observed that there are other ways for HMRC to collect the liabilities, but HMRC was out of time in respect of some of them.

What all of this goes to show is that our tax system is creaking at the sides. As more and more complexity is added, it not only becomes more complicated for those of us trying to advise and support clients, it also becomes increasingly challenging to administer effectively.

Removing complexity

There is an argument for empowering the OTS to look not only at the way that tax law works in some detail, but also to advise on simplifying the ‘on the ground’ delivery of the tax system.

Nobody with a good overall view of the tax system and how it operates for individuals would have thought the development of the capital gains tax (CGT) reporting portal for residential property gains that we now have would be a sensible way to deliver the policy objective. A standalone IT system that is not linked into the self assessment system, where other gains and losses and the income determining the rate of tax payable on that gain are reported and dealt with, is a quite staggeringly daft idea. And we (and indeed HMRC) are now reaping the harvest of that, not only in trying to deal with the differences in liabilities that are arising when overpaid CGT cannot be set against income tax that is due, but in the establishment of additional taxpayer records outwith the self assessment system, the appointment of agents who are already acting for the taxpayer and possibly other problems that have yet to emerge.

Will someone call a halt to all of this? I consider it unlikely. Ministers all have their pet projects and like to leave their mark, and it is probably true to say that nobody is remembered for getting rid of what we might regard as unnecessary complexity.

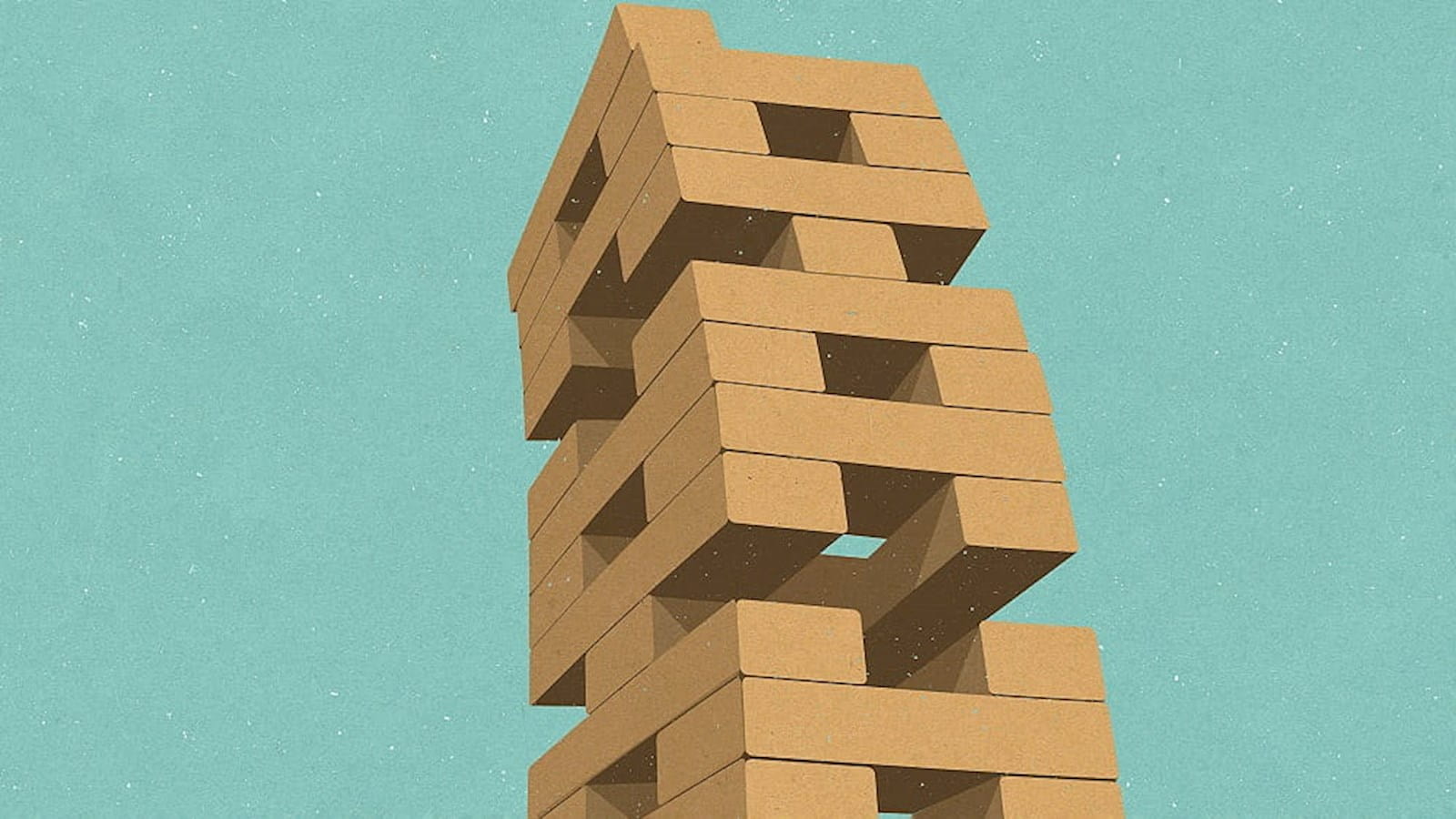

I remember reading an article on complexity in the tax system some years ago (when, we must agree, things probably were a lot simpler than they are today). The author pointed out that such a vast and complex ‘Lego tower’ of interrelated tax measures risks becoming unstable as more and more measures are added. A bit on the side here and extra projection there, and then add a few more bits to the bits you have just added – measures that have a byzantine dependency on other measures, so that simplifying becomes almost impossible without dismantling the entire structure and starting again from the ground up.

But if significant simplification is probably an unachievable dream, maybe we could plead for the OTS to be given remit to look at how measures are delivered in practice, and to be involved ‘upstream’ at the design stage so that we at least get to reduce the entropy naturally present in the UK tax system today. For the scientists among the readers, I make a plea to reverse the second law of thermodynamics as it applies to our tax system – a law that says that entropy always increases over time.

About the author

Rebecca Benneyworth, tax speaker, writer and consultant, and Vice-Chairman of the Tax Faculty