To conduct rich and engaging strategic conversations with the executive team in a world of deep uncertainties and surprises, boards are helped by using scenario planning. Dr Trudi Lang, a senior fellow in management practice at the University of Oxford’s Saïd Business School, explains how scenarios help to reframe current understandings of potential changes in the firm’s context, to identify new options, and successfully revise the firm’s strategy.

This guide for boards is intended to provide a comprehensive overview of the process of developing and using scenarios. It is based on the Oxford approach, which has been developed through practice, research and teaching over the last 20 years at the University of Oxford, and is taught in the award-winning Oxford Scenarios Programme. If your board is new to scenario planning, the guide will enable you to move through the specific steps involved, and if your board is familiar with scenario planning, it will hopefully provide new ideas to develop the way you go about it.

Scenarios are plausible understandings of the significantly different ways the radical or deep uncertainty in a firm’s future context could play out (two to four scenarios are included in a set). They help boards and the executive team reframe their understanding of potential developments and are used to review current strategies and create new options.

Scenarios are developed through rich, engaging strategic conversations providing an excellent forum for board members and management to come together to explore their assumptions about the future and to develop a shared understanding about strategic options. In this way, the development of scenarios and their related options provides an effective mechanism for cooperation between boards and executive teams.

Scenarios can be used by boards and the executive team to review proposals and monitor developments as a form of stress testing. For example, after developing a set of scenarios in 2016, the UK-based Rolls Royce, a leading supplier of power systems for aircraft and the marine and energy sectors, used those scenarios to test and adapt its investment proposals. The proposals that didn’t perform well across the scenarios were rejected. This is an example of the way scenarios can be used by boards in their role as overseer in the firm’s pursuit of its strategic directions.

Every board – whether it is explicit or not – works with a future scenario of their firm’s context in mind when contributing to and assessing strategies proposed by the executive team. Often this scenario is a set of beliefs that remain implicit. In stable times this may be a reasonable approach, but in times of increasing uncertainty it can lead to the board being blindsided, and their firm disadvantaged.

The number of uncertainties that all companies must now deal with, such as supply chain disruptions, energy price hikes, geopolitical tensions, technological shifts, pandemics, and climate change, working with one scenario can be problematic. The deep uncertainty that firms must operate with today means boards can’t be sure how things will unfold. This makes judgements about what is more, or less, probable (as is often done when identifying risks) extremely difficult.

Instead, in a world of surprises, working explicitly with a few plausible scenarios rather than just the single implicit one enables boards to take anticipatory action, and reduce their risk of suffering paralysis, strategic blindness, or reactive delays.

Regulators are increasingly acknowledging this, asking boards to stress test their organisation against different climate change scenarios.

But not only does strategising with a set of scenarios help boards be more proactive, it also helps them balance their dual governing roles of (1) working with the executive team to devise the firm’s strategy, and (2) then overseeing the strategy’s execution to ensure the best interests of the organisation and its stakeholders are met. This dual role of cooperation and oversight can be a difficult balancing act, but it is invaluable for firms when it works well.

Seven aspects

Seven aspects make up the process of scenario planning, which are often conducted iteratively. It is not uncommon to return to previous stages as more is learnt and the focus usefully shifts.

1) Define the user and use

It’s vital to understand that scenarios explore the uncertainty of the firm’s future context for someone for a specific purpose. So the first step is determining (a) who the scenarios are for; (b) for what purpose are they being developed; and (c) exactly how the outcomes will be used and when.

For example, are the scenarios to assist the board and the executive team with the development of the organisation’s strategic plan? Are they to help test a major investment proposal? Are they to understand significant changes in the business environment? Or are they to explore what new collaborations and partnerships might be needed for the firm to achieve its strategic objectives?

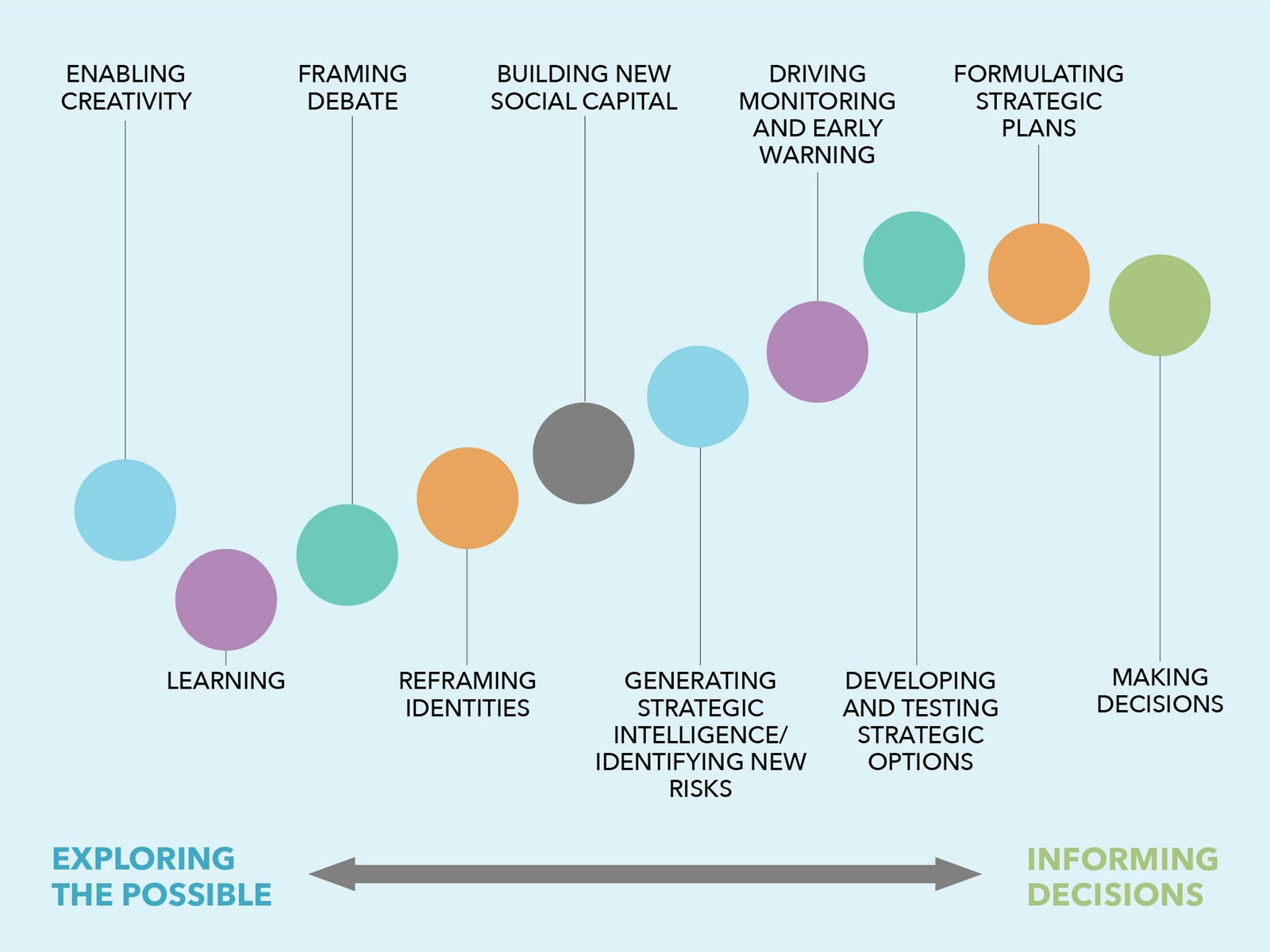

Scenarios can be used for many purposes, as figure 2 shows, and it is crucial for all involved to be clear on the purpose of the scenarios as it informs everything that follows. However, it can also be revised during the process if that is found to be helpful.

Understanding the purpose of each scenario planning engagement is also how to judge its success: did it help the board and executive team with the stated purpose?

2) Scope the process

Scenarios are created and used by moving between well-facilitated strategic conversations and desk research. A small organisational team can help execute this process, preparing inputs, organising, and helping facilitate conversations with the board, as well as compiling the outputs.

A key consideration is what new external perspectives might be helpful to bring into the discussions? The board and executive team may feel it does not have enough knowledge about certain emerging developments (eg, cryptocurrencies) and speaking with well-informed people outside the organisation can bring in valuable new insights.

Deciding who to involve in the production and use of the scenarios is not only about gaining access to good insights and perspectives, but also represents an opportunity to build new relationships and shared understanding. So, another question to guide the choice of who to involve, is who might it be helpful for the firm to develop new relationships with?

Finally, how you might conduct the conversations among the board, executive team, and other participants (where relevant) needs to be considered. When the scenarios are being developed and explored, these strategic conversations may be best held outside the procedural constraints of normal board agendas. One option, for example, could be to hold one workshop meeting as part of building the scenarios, and a second one exploring their strategic implications. On an ongoing basis, using the scenarios to review management proposals can be accommodated in the formal board agenda.

3) Map the strategic environment

Core to the Oxford approach to scenarios is the need to differentiate between the business environment and the broader contextual environment that shapes it. A firm’s business or transactional environment is made up of the actors it engages with to achieve its strategic objectives. These can include clients/customers, governments, investors, suppliers, partners, etc.

These actors in turn sit within a wider contextual environment that over time influences and at times significantly reconfigures the business environment. That is, factors in the contextual environment, such as technology developments, energy prices, policies and laws, climate change, macroeconomic factors, etc, affect the behaviour and make-up of actors in the business environment.

Scenarios are thus different configurations of a firm’s future business environment that arise from the effect of uncertain changes emanating from the contextual environment (see figure 3).

To create the scenarios, the business environment is mapped by listing the actors the firm interacts with in relation to the purpose of the scenarios work, such as developing the firm’s strategy (phase 1). This then enables the relevant factors in the contextual environment that could significantly reshape the make-up and behaviour of these actors to be identified. Some of the factors may be new to board members, so the team running the scenario planning sessions may need to do further research (including interviews) or provide special briefings.

Once these factors have been mapped, a time horizon is identified for the scenarios. The time horizon can be thought of as a number of years in the future (eg, 5, 10, 20, etc) that allows you to look back at the present and see something anew.

4) Build the scenarios

To recap, scenarios are different and insightful configurations of an organisation’s future business environment that stem from changes in the contextual environment (the firm itself is NOT described in the scenarios).

There are different methods for structuring scenarios. One is to choose two independent factors to create a matrix and flesh out the scenarios that result from this combination. Alternatively, you can choose a group of interdependent factors, and tell a story or map a system to explore how the factors meaningfully relate to each other.

The result is a description of two to four scenarios in the year of the time horizon (5, 10 years ahead, etc).

Board members can then explore how these worlds would evolve from the present. Connecting the present and the future is very important for subsequently using the scenarios because it points to what could happen in the near term and thus what should be the first focus of attention. Stories are used to explain the details of each scenario as they are the best way of bringing together many different and unfolding factors to describe different plausible futures.

Three criteria can be used to check whether the scenarios are ready for use. The degree to which they are:

- relevant for the purpose they have been developed (as determined in phase 1);

- plausible; and

- challenging in that they contrast helpfully with the scenario that underpins the current strategy.

Adapting an existing set of scenarios

An alternative to developing your own set of scenarios is for the board and executive team to use a set that has been developed by another organisation. Many sets of scenarios exist in the public domain for this purpose. While it is much better to develop your own scenarios, if you choose to use somebody else’s they need to be tailored to your specific situation first. Saïd Business School academics Lang and Ramirez outline five ways to adapt the scenarios to your firm and specific strategic situation (link below).

5) Assess the future business environment

Once the scenarios have been developed, they can be used to understand how the business environment as mapped in phase 3 would evolve and change in each scenario.

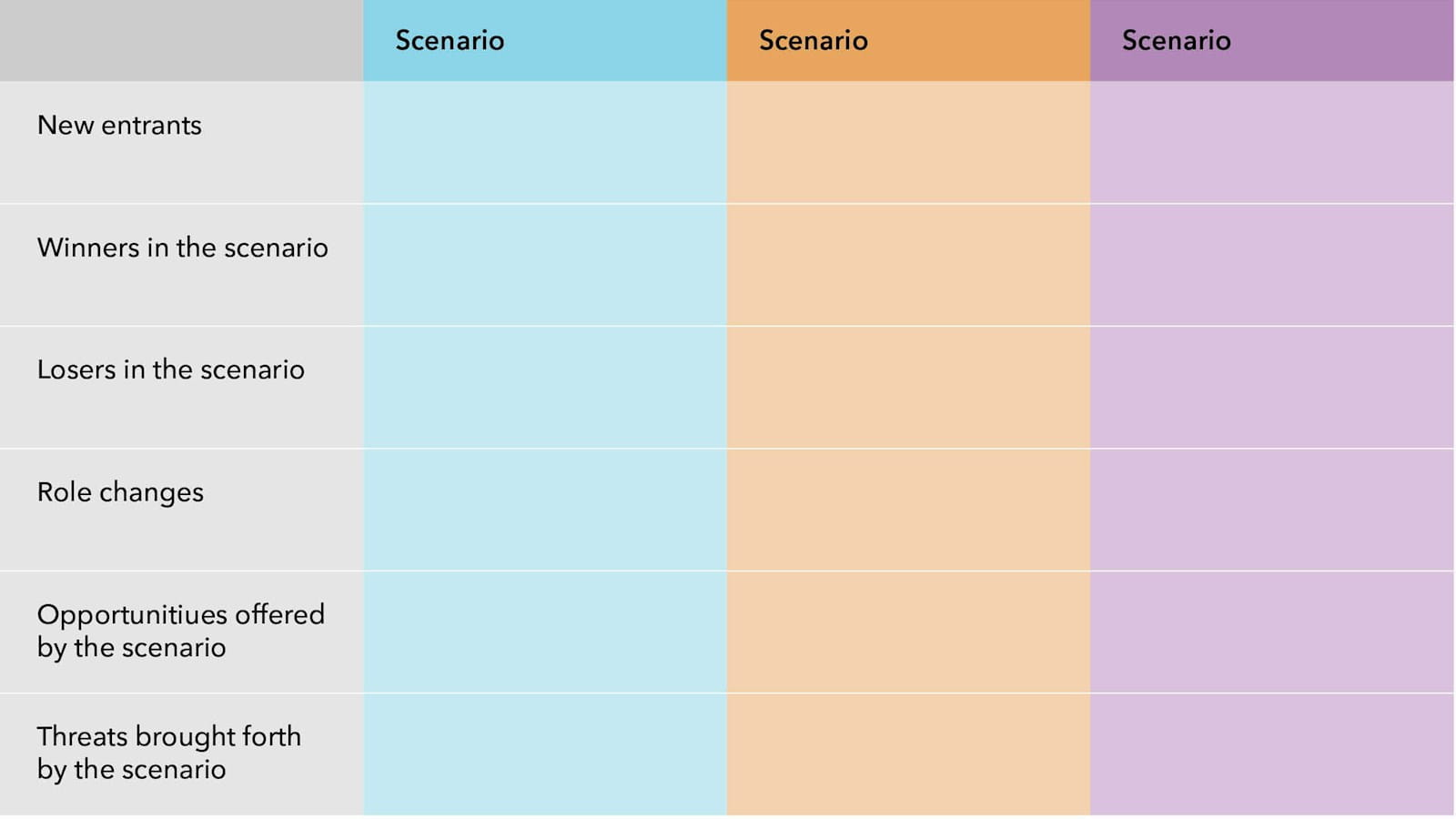

Areas of interest for the board and executive team to explore include understanding which new actors appear, how roles change (eg, has a client become a competitor?), who is doing well, who is doing less well, how relationships between organisations change, and what opportunities and challenges or threats emerge (as outlined in table 1)?

6) Review the strategy and generate new options

The specific details about how the scenarios will be used will relate to the stated purpose (phase 1) for which the scenarios were created, but there are two broad ways of approaching their use in strategy.

- Review the current strategy. In a process known as “wind tunnelling” (from the use of wind tunnels to stress test a plane), board members and executive teams can use scenarios of the firm’s future context to test their current strategy in a similar way. This process highlights possible circumstances that the strategy doesn’t adequately address and prompts the board and executive team to identify new strategic options. Similarly, boards can use the scenarios to assess new strategic proposals (eg, capital investments) proposed by the executive team. The scenarios provide a range of helpful contexts within which to discuss and evaluate the proposal.

- Generate new options. The scenarios can also be used to generate new options. Each scenario is approached by asking what options would enable the firm to do well in this world. These options might include pursuing new collaborations, developing new services, expanding into different markets, etc. It is useful to look at the options as a set to ensure they work well together. The options are then looked at across all the scenarios to see which are common and which are scenario dependent. If the options are common across the scenarios or can be easily tweaked to be so, they can be explored for direct inclusion in the firm’s strategic plan as they represent good choices no matter which of the scenarios unfolds. Where the options are scenario-dependent, a strategy playbook approach can be used such that the scenarios are monitored and the relevant options activated as needed (see the special report on pivoting for further details about strategy playbooks). One way to manage scenario-dependent options can be through a process called staging. Here, the key options are divided into stages of development or investment. That is, what would be required to execute the option in stages over the next few years, the middle years, and finally towards the end of the scenario? This enables small investments to be made in the immediate future for each of the scenarios providing good optionality while not over-committing the firm. Once it is clear which of the scenarios is becoming dominant, the options for the other two scenarios can be divested or adapted for another purpose.

Finally, whether you are adapting the current strategy or pursuing new strategic initiatives it is important these new directions make sense not only in terms of the future, but also the past. For strategies to resonate and have power in the present for success in the future, the firm’s past, including its identity, may need to be reframed.

7) Navigate with the scenarios

By monitoring the scenarios using relevant “early-warning indicators”, the board and executive team can understand emerging contextual changes and proactively adapt the organisation’s strategy. In this way, scenarios help beyond the immediate identification of options and strategies, enabling the firm to effectively navigate a world full of surprises and sudden changes.

Trudi Lang is a senior fellow in management practice at the University of Oxford’s Saïd Business School, and a core faculty member of the Oxford Scenarios Programme. She also co-directs the online Oxford Executive Strategy Programme and was previously director of strategic foresight at the World Economic Forum.

CPD courses for boards

ICAEW offers virtual CPD courses to support those considering becoming a board member and those who have recently joined a board, as well as those looking to develop their skills as a board director.