Organisations have much to gain from using stakeholder maps to build trust and make better decisions.

For board members to steward their organisations to long-term success in today’s unpredictable operating environment, they need to take a more wide-angle view of the company and its operations than has traditionally been the case. Gone are the days of only prioritising stellar financial performance and a healthy dividend for shareholders in the next financial year.

Many boards and the companies they serve are already well aware of how useful it is to track, understand and prioritise good employee and customer relations, but the most progressive boards certainly don’t stop there: they take a more extended view and develop an in-depth understanding of all stakeholders on whom their organisation has a material impact and, just as importantly, all stakeholders who can have a material impact on their future plans, too.

Stakeholder maps sit at the heart of this exercise in identifying and engaging key stakeholders. Although board members won’t be creating stakeholder maps themselves, it will pay to understand what should go into creating an effective one and – most importantly – how to get the most from it. Stakeholder maps can be used for many purposes, from informing future strategy and identifying risks to improving sustainability and implementing new regulations. Their ultimate benefit, however, lies in helping companies build trust in their brand and drive better decision-making.

This five-part guide details why stakeholder mapping and engagement matters for all senior decision-makers, and looks at how senior managers – including the board – should approach stakeholder relationship management practically. It then sets out the core underlying principles to successful stakeholder management, explains how to create a stakeholder map and concludes by examining how to use stakeholder maps to build trusted relationships.

1. The importance of stakeholder mapping and engagement

“Whatever you're doing, whether it’s making steel or selling a mortgage, you can only go so far without the trust and support of the communities where you work and the people that you’re working with,” states Brendan McNamara, a former Head of NGO Engagement at a global bank. Therein lies the crux of why stakeholder mapping and engagement is important. No company is an island and to fulfil its potential it needs to build strong relations with the wider world.

In identifying and building stakeholder relationships, companies stand to realise a number of benefits. First, stakeholder mapping can help boards identify emerging issues and improve decision-making. “As the steward of a company, the role of a board is to think three steps ahead and a proper stakeholder analysis will help the board achieve this,” states Mike Tuffrey, Co-founder of Corporate Citizenship, a global consulting firm, specialising in responsible and sustainable business. “If you think of a radar screen, stakeholder mapping and engagement helps boards identify not just the issues that are flashing in the middle, but alerts them to those that are just starting to flash at the edges, signalling a potential issue or opportunity. It also feeds into board decision-making, by enabling boards to understand different audiences and prioritise actions.”

Stakeholder maps can also allow companies and their boards to adopt a much more robust approach to their strategic planning. “Stakeholder maps are important because they give you a certain intentionality about what you’re doing,” says Richard Spencer, Director of Sustainability at the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW). “The temptation with stakeholders is to think of it very much in one direction, namely about who it is you want to speak to. Often that translates into who’s going to agree with you, so you end up with a very small piece of the wider picture. A stakeholder map gives you a really good structure for clarifying your position, as well as understanding who may not agree with you.”

In a similar vein, stakeholder management can help companies gain a different perspective on key issues and risks. Peter van Veen, Director of Corporate Governance and Stewardship at ICAEW, explains: “Stakeholders can bring a deeper understanding of the risks that you’re facing looked at in a different way, which is a really important benefit to a company in terms of risk management and its response.”

Finally, stakeholder mapping can also help companies access support and help. This is particularly useful when there are industry-wide topics or regulatory developments that companies need to address. Talking to other stakeholders, including competitors, can help develop thinking and identify next steps. Van Veen states: “When the Modern Slavery Act came into force, many companies would have thought ‘what on earth do we need to do?’ A dialogue with suppliers and employees is important, but also with NGOs who track issues in your industry or supply chain. The important thing is to also realise that you can ask for support, particularly in areas such as employment conditions in the supply chain where the stakes can be very high.” Industry forums such as AIM Progress, an initiative to improve fast-moving consumer goods supply chains, provide safe spaces for companies to discuss and define their approach to common, non-competitive issues.

2. Managing stakeholder mapping and engagement

When it comes to managing the process of stakeholder mapping and engagement, the approach varies by the size of the company. In large multinationals, there will often be dedicated stakeholder relations divisions; in medium-sized companies, this role often falls to corporate communications or, depending on the project, divisional heads. Human Resources (HR) may lead on employee relation projects, for example, or sustainability teams may manage environmental, social and governance-related stakeholders.

For small companies, it is often senior management that needs to take the lead and be strongly supported by the board. “For smaller companies, stakeholder management can be a bit more challenging but, regardless of size, the CEO really needs to take responsibility and ensure they are in tune with their stakeholders,” says Van Veen.

3. Key principles of successful stakeholder engagement

In conducting any stakeholder mapping and engagement exercises, there are some key underlying principles that boards and management teams should adopt throughout – regardless of the size or scope of their organisation – to ensure a best-practice approach and engender success.

Principle one: successful stakeholder engagement is about listening, not transmitting messages

“If people see stakeholder maps as a way to target key messages more ruthlessly at stakeholders and make sure that they land, that is the wrong mentality,” states Tuffrey. “If they think stakeholder mapping is about telling the company’s story better, then, at the very least, they’re starting in the wrong place and will most likely fail. I would go as far as to say that stakeholder maps are useful if they help the company listen better.”

Principle two: successful stakeholder engagement is about recognising it is a reciprocal relationship

In working with stakeholders, it is important to take a two-way view on the relationship – essentially, the impact the company has on the stakeholder and the impact the stakeholder has on the company. “Often, stakeholder mapping can be outward exercises about which people the company understands to be its stakeholders,” Spencer says. “But companies also need to think about who considers themselves to be a stakeholder of the company. This also helps to drive the ‘why’ of the relationship.”

Principle three: successful stakeholder engagement is about showing a willingness to learn

Companies need to be honest and open in their interactions with stakeholders. Often, the tendency is to focus only on the good news and to not talk about the things they are unsure about or that are not going so well. “Companies are very bad at asking for help,” states Tuffrey. “They seem to be hard-wired to be all powerful and do not want to show any weakness or flaws, but a degree of humility and being prepared to explain constraints and show a willingness to learn helps to build better relations.”

4. Creating a stakeholder map

Step 1: establish the purpose of the map

When creating a stakeholder map, the very first step is to establish the purpose of the mapping exercise and how the end map will be used. Van Veen advises: “It’s important to start with ‘What's the risk I am trying to address?’ And then to consider ‘What role do these stakeholders play in that?’ Depending on the risk you are trying to address, different stakeholders will play very different roles.”

There are a variety of reasons for creating stakeholder maps. They can be to address specific, thorny issues, such as corruption. It may be that there is a strategic shift, for example, repositioning the company as a sustainable brand. Or there may not be a specific issue or set project, but a recognition that stakeholder engagement can help shape future planning and thinking and it is beneficial to bring those voices into the mix. Whatever it is, it must be clearly established at the outset.

Step 2: identify stakeholder groups – especially the non-obvious ones – and segment accordingly

Once the purpose of the stakeholder mapping exercise has been defined, the creation of the map can take place.

The stakeholder categories that need to be considered in any exercise will, of course, vary by the purpose of the map, as well as the company’s sector, its legal status and target market. For example, manufacturing industries are likely to be concerned with any manual labour in their supply chain, or heavy industry will have a particular focus on waste or emissions from their production processes. For service industries, these issues can be less problematic, but it does not mean they are immune to them. They still have suppliers, for example, but the supply chain just tends to be less complex than for a manufacturer.

B2C companies have the added pressure of direct consumer pressure on their operations and management decisions. With the rise and rise of ethical shopping, a growing number of consumers are making purchasing decisions based on companies’ environmental and social impact. While B2B companies may not have this direct pressure, their customers further down the value chain will be keen to scrutinise their own supply chains and consumer groups are also increasingly savvy about checking the social and environmental records of all parts of a supply chain.

For most companies, the broad categories to include in any mapping exercise include:

- External stakeholders in the supply chain, such as investors, suppliers, distributors, customers.

- Other external stakeholders, such as regulators, governments, competitors, local communities, activist organisations

- Internal stakeholders, such as employees and contractors

However, across all of these broad categories, there is often a lot of drilling down to identify individual sub-groups. Tuffrey explains: “There is a lot of unpicking of stakeholder groups that has to happen. Take employees: you have direct employees, then you've got people who are working on your sites who are not your employees because they’re doing the catering or cleaning and are provided by a third-party. You’ve also got contractors that you outsource work to. And then there are even the employees of the future to consider. This unpicking has to happen for all categories.”

One particularly important category of stakeholder for companies to bring into mapping exercises is the critical voices and those that challenge the company. “Critical voices are very important stakeholders to map and interact with because they are the ones willing to give unvarnished, constructive feedback. Many of the larger NGOs, such as Transparency International and Oxfam, fall into that camp,” states Van Veen. These ‘critical friends’ will often tell you what your own staff will not.”

Spencer adds: “There is value in what I call constructive disagreement. In other words, if we found somebody who just agreed with us, you’ve just got endless confirmation bias. If, on the other hand, you’ve got somebody who just violently disagrees with everything you say and is always going to be polarised, that’s not going to be productive either. But what you do need is somebody who disagrees with you in a constructive and positive way. That’s so rare nowadays because we think that disagreement is a bad thing.”

Finally, it is also important for companies to take a step back and consider if there are any unknown voices that they are not including in the conversation. Here, strong risk management processes can help. “If you’re doing your risk mapping correctly and really looking at where your most significant risks are, particularly the reputational risks, this is where you should be putting a lot of your stakeholder management efforts,” says Van Veen. “You need to think, ‘Which are the voices that we might not be listening to or hearing and how do we interact with them? How do we connect to these stakeholders and get on top of those risks?’ Rather than wait for an issue to arise and those voices to start shouting, try to get ahead and start identifying and building those relationships.”

Step 3: prioritise stakeholders and review maps regularly

Once the key stakeholders are identified, they should then be prioritised in line with the purpose of the mapping exercise. “Not all stakeholders are equal,” states Tuffrey. “However, it’s not quite as simple as saying one group of stakeholders is more important than the other. Their importance can vary according to the situation. It can be complex: a stakeholder may interact with a company in different ways and be more important at different times; they might not be so important now, but they will be in the future.”

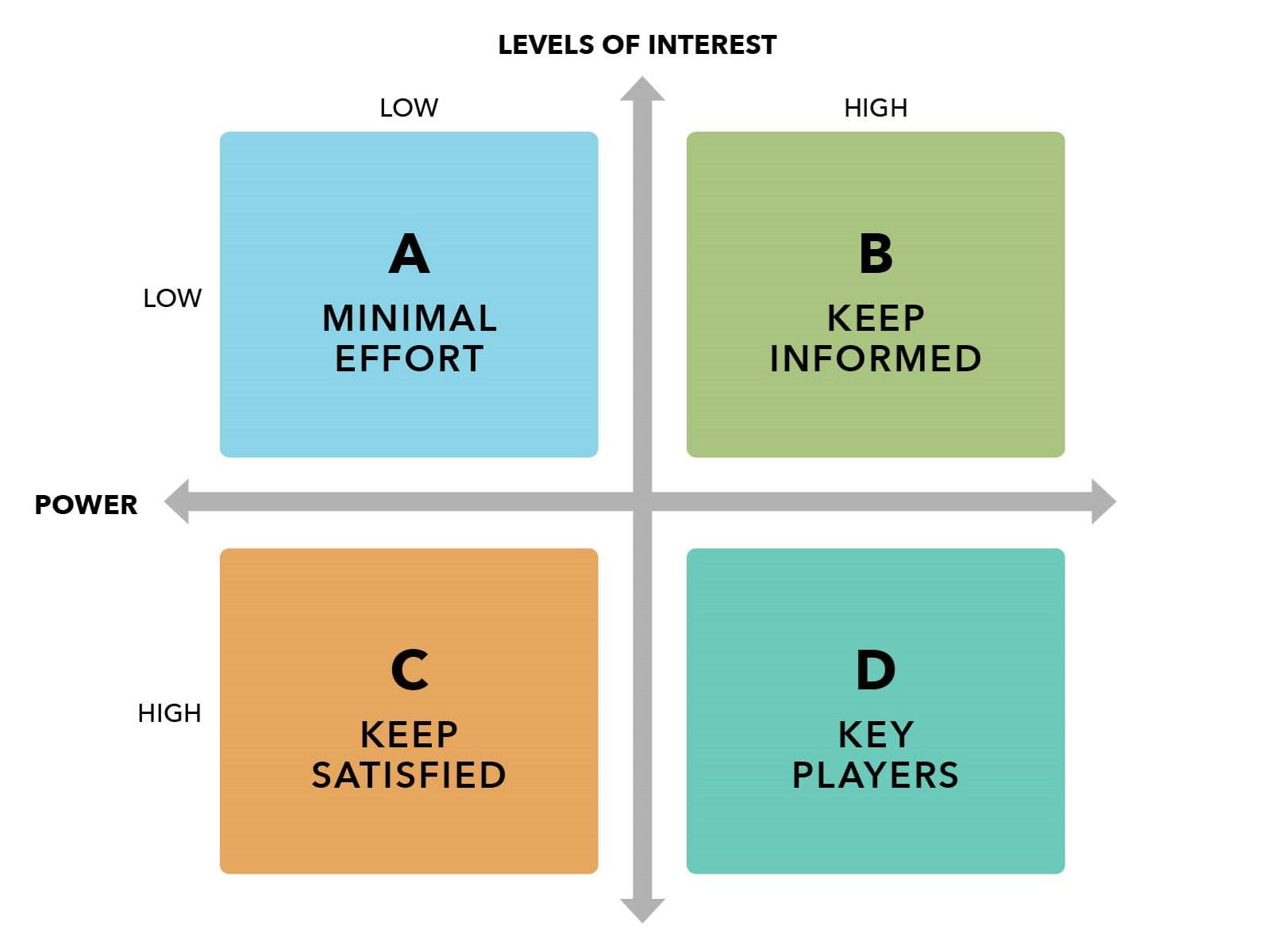

Some companies use an approach known as Mendelow’s Matrix (see figure 1) to prioritise stakeholders. This approach can have its benefits, but companies should be aware of relying on it too much. “The four-by-four matrix approach is very common,” says Tuffrey. “However, it can often fall into the ‘how do we transmit our messages to stakeholders?’ trap rather than genuinely mapping them.”

The changing status of stakeholders also highlights the importance of reviewing maps regularly. Stakeholder mapping should not be viewed as a static, one-off exercise. If they are to be used as a tool to help a business fulfil its objectives or a given project, they need to be reviewed dynamically in line with those objectives or project needs.

5. Using a stakeholder map to build trusted relations

While boards won’t be directly involved in putting a stakeholder map together, their support will be important. The advice below should provide some guidance for board members on what they should expect from their management team on making use of a stakeholder map and how they can provide the right level of support.

Develop an action plan and share this with the business

The true value of a stakeholder map ultimately lies in putting it to use in helping the company find a solution to the problem identified at the start of the exercise. “A stakeholder map gives you a good starting point. It gives you direction and helps you prioritise where you’re going to put your assets –whether that’s human or capital – in working on those stakeholder relationships, but you need to put in place a plan,” explains McNamara.

With this in mind, a useful exercise can be to undertake a gap analysis comparing stakeholders’ perception of the company and what the company believes is the reality, with a view to creating a plan to close that gap. Tuffrey explains: “There are two gaps to fill there – an understanding gap and an expectations gap. Having identified those gaps, put in place a plan to deal with them. There’s no point having a great mapping exercise and gap analysis if you’re not going to do something about it. The board can then pull out that action plan periodically to assess how the company is going about closing the gap.”

It is also important to cascade any plan to ensure that it is used and adopted by the relevant functions within the business.

Be open, honest and authentic in your interactions

A key aim of companies that are serious about stakeholder engagement is to build good relationships, and trust is an intrinsic part of that. “Good relationships are built on trust,” says Tuffrey. “In the context of a company, a key element of trust is that you consistently do what you say you’re going to do. It isn’t about promising the earth, but it is about being open and honest about what you are going to do and what you’re not going to do. And if you haven't done what you said you were going to do, then be open about that. Frankly, most companies aren’t very good at this because they only want to show the good news. But that’s not real, everyone knows it’s not real, and that’s not how you build trust.”

Given this context, it is important for companies and their stakeholders to establish what constitutes ‘success’ for the matter under discussion, then put in place key milestones and review those milestones along the way. It also means being very clear about who has to deliver what outcome and by when. This transparency and delivering on all that’s promised will help to build trust further.

Make someone responsible for managing actions and next steps

In holding these conversations and setting goals, one of the biggest challenges can be for companies to keep track of the different strands of interaction. As discussed above, large multinationals may have stakeholder relations teams, but in smaller companies it needs to be considered where this responsibility lies. It can vary according to the project, but putting in place some dedicated resource or allocating a project lead is an important consideration.

Van Veen says: “The interactions with stakeholders can be with many different contact points in many different geographical locations, so companies need to think about how they stay on top of all of that. From my former roles at NGOs, it was very clear to see which companies were organised and on top of things and which weren’t.”

Ensure that the board has a strong commitment to stakeholder relations

Once a plan is in place and goals have been set, there also has to be commitment from the board that it is happy to take action and ensure follow-up as appropriate. McNamara says: “You have to have buy-in from the board and senior management. There has to be the understanding that there will be consequences once you start listening because people will ask you to do things. So, if you are going to listen, you have to be prepared to act or explain why you are not doing so.”

To aid this commitment from the board, it is important to brief and report back to it on interactions with stakeholders. “Board members don’t live in a vacuum,” states Van Veen. “They will read in the media if an NGO is criticising the company or if staff are complaining on Glassdoor. So you need to show you are on top of that. Boards tend to be time poor, so you need a well-managed process to have those issues summarised for board members.”

For internal stakeholder relations, it can also be useful to consider what channels there are for board members to have a good feel for what is going on at the company. In some countries, it is common to have a ‘voice of the employees’ representative on the board. Another approach some boards adopt is to hold ad-hoc internal workshops to gauge employee opinions and sentiment.

Finally, the board plays a vital role in developing a culture that is conducive to successful stakeholder mapping and engagement.

Non-executive directors, in particular, can be pivotal in helping companies to overcome an in-built culture of operating in a vacuum and instead listen to and engage with the rest of the world. Tuffrey concludes: “There is an embedding of culture that that the board is responsible for. For stakeholder engagement to be successful, that needs to be a culture of honesty, trustworthiness and listening that is part of the company’s DNA.”