Organisational restructuring can bring with it a wealth of issues, one of which is a change in culture. Andrew Mayo offers advice on how to manage cultural adaptation in a way that improves, rather than compromises, business strategy and employee behaviour.

In the May 2011 issue of F&M, I discussed the management of change, and I shall now expand this further, specifically to study the area of culture and cultural change.

Most organisational leaders would love to have a coherent, consistent, unifying culture that epitomises the kind of company that they and their stakeholders would love to see.

It is indeed a worthwhile ambition. Many of the world’s greatest companies are associated with a distinctive and long-lasting culture that is independent of any individual, even the CEO. Many of them of course were originally shaped by influential and powerful CEOs in their early years, as companies such as Google and Facebook are today. Porras and Collins in their famous research entitled Built to Last found that one of the characteristics of sustained success was the strength of the culture, reinforced by a policy of internal promotion. People share the same sense of ‘what is OK and what is not OK’, and have a common language – all of which tends towards more efficient working and less destructive politics.

Yet the modern world presents many obstacles to such continuity. Organisational restructuring, through acquisition and divestment, dilutes and merges cultures. Each new CEO wants to make their mark by doing things differently. True, research by Spencer Stuart in the US and Europe shows that 70% of CEOs are inside appointments. But some of those will have been brought in shortly before as CEOs in waiting, and any outsider cannot avoid bringing in their own ideas of what makes an organisation effective.

There are often good arguments for consciously seeking the new broom. A self-reinforcing culture can lead to stagnation, complacency and arrogance – and these are indeed dangers. The board of IBM brought in their first ever external CEO in the 1990s, Lou Gerstner, deliberately to shake up the company, and he did a remarkable job – despite having no prior IT industry experience. However cultures that have developed as dynamic and innovative in themselves do avoid the risks.

Adapting – or in some cases revolutionising – the culture is necessary at some time for all organisations. No culture gets changed by the visionary speech. It needs systematic, disciplined and shared effort. This article looks at one route to success.

The constituents of culture

Academic definitions of culture abound, but the simplest is ‘the way we do things around here’. The emphasis is on ‘do’ and if we want to change things it is because we want people to ‘do’ things differently. But the question is why do we do things the way we do?

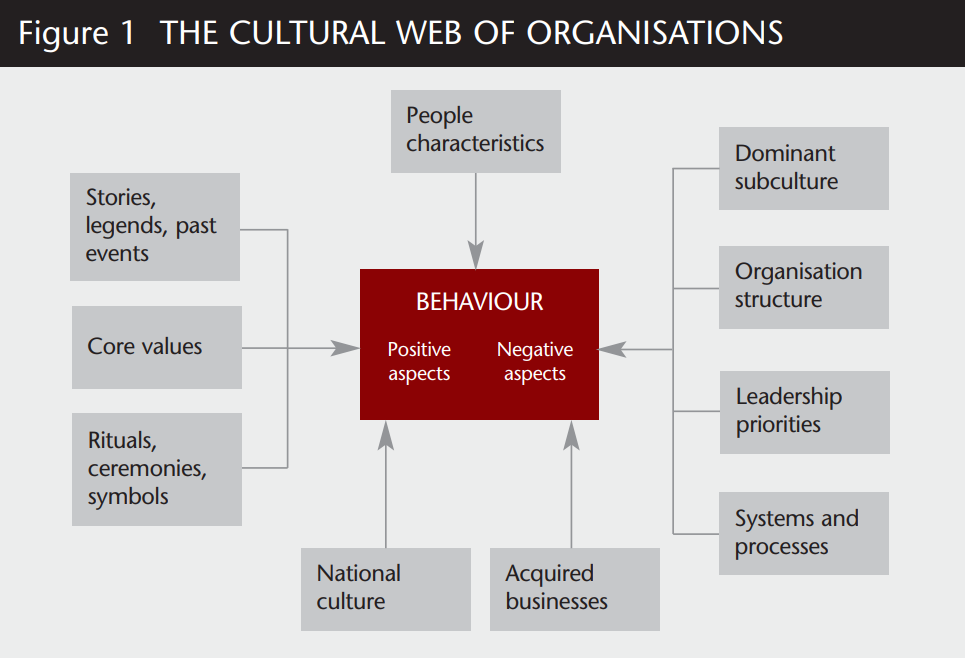

One of the helpful models for understanding this is called the ‘cultural web’. The original model was developed by Gerry Johnson and Kevan Scholes and has proved a useful tool for analysing the levers of cultural change. Figure 1, below, is an adaptation of that model.

In the centre are the visible manifestations of the culture – the way people behave, how they communicate, the language they use and so on. The ‘web’ enables us to match the influences that have shaped this. Some of these are historical and some are present. Some can be changed and some cannot.

Let us look briefly at these influences and take them in a suggested order of ‘difficulty of change’.

- National culture – meaning the national culture of the home base of the organisation. Within nations there are local variations of course, but this shapes a lot of the inherent values of an organisation. International organisations need to be sensitive to applying what is perfectly acceptable at home to their operations around the world.

- Stories, legends and past events (and past dominant characters) – look around an organisation, especially head office, and see what is on the walls. We cannot change history but sometimes we need to move on and not allow it to influence the present.

- Core values – these drive a lot of the informal behaviour and are not easily changed if they are firmly and historically embedded, such as in organisations with a high average length of service. Having a new set of values published does not in itself change anything, and we will come back to this. Mergers with parties which have radically different core values rarely succeed.

- Acquired businesses – when companies ‘merge’, one culture usually dominates and that is dictated by the composition of the senior leadership team, not necessarily by which component was the bigger in size. The merged culture may well develop some differences, but they will probably be small. People in the organisations, however, will retain their own set of ‘heritage’ values for many years and form sub groups of camaraderie.

- The dominant sub culture – in some companies the dominant power is that exerted by accountants (more and more in fact); others by engineers (less and less); or by sales and marketing. In the IT company I worked in, its early pioneering days were driven by engineers but sales soon took over and dominated for years – to the detriment of profitability. Finally finance took the lead.

- People characteristics – this is related to the subculture and to the core values, but some organisations attract certain types of people. For example, ‘big company’ v ‘small company’ mindsets, work hard-play hard people (many boutique companies), lively personalities (eg Virgin), undisciplined individualists (some media companies) and so on.

- Leadership priorities – strong leaders undoubtedly stamp their mark, and the best have a clear vision of what their organisation should be like. They need time to initiate and embed change, but unflinching determination succeeds. It is a constant issue for boards to review the leaders they have and ensure they are right for the times.

- Systems and processes – these have perhaps the major influence on the behaviour of people as they dictate much of what they do day by day. Whatever other changes happen – new leaders, new value sets, new symbols – if processes are not changed to match them, things will go on day to day much as before.

- Rituals, ceremonies and symbols – these are perhaps less prominent in modern organisations than previously, but all readers can probably list a few from their own. New ones can be introduced to reinforce desired changes.

- Organisation structure – the easiest change to make, and a tool frequently used by new leaders at all levels to stamp their arrival. Radical change – such as switching from hierarchy to process based, or geographical to matrix – can certainly change the culture but without care just causes confusion. Many changes are, however, of the Titanic deckchairs variety.

The value of culture mapping

Many change efforts fail because there is a focus on one aspect of the organisation (structure, for example) and the complex interaction of past and present forces are not considered.

What mapping organisational culture does for us is the following:

- Surfacing that which is taken for granted – so that it is possible to question the status quo. (If no one ever questions what is taken for granted then, inevitably, change will be difficult.)

- Mapping the influences on current behaviour – making it possible to see where barriers to change exist, and analyse the strength of the various factors; and

- Highlighting the ‘levers’ that can be pulled – enabling the creation of effective change.

So when we want to change culture, the first step is to make this map for the current state. We then rewrite the central section with the behaviours we want to see, all positive of course. Each of the influences can then be examined to see which need adjusting to provide integrated, holistic successful change.

Many change efforts fail because the complex interaction of past and present forces are not considered.

The process of cultural change

Just as for any change project we need a disciplined and systematic approach. The starting point of all change must be to define what will be different after the change. Often in the area of culture we have visionary aspirations that are not anchored in anything very tangible. ‘We need to have more empowerment’, may be the cry, for example – but in what areas? For whom? How much? And so on.

The starting point of the process we suggest is that a facilitator works with the senior team to do the following:

- Imagine it is five years hence, and we have been successful in achieving our business goals over this period;

- Take each stakeholder in turn and describe what it is like for them to interact with the organisation;

- Come up with a series of statements which describe what and how people in the organisation behave;

- Rate each of them ‘high’, ‘medium’ or ‘low’ for the importance of their impact on the business and its stakeholders;

- Score them out of 10, or by using traffic lights, on how close the organisation is now to those statements;

- Analyse the scores and make a plan for strengthening the strengths and moving forward on critical deficits; and

- Use the set of statements as an instrument for periodic checking on progress.

Often organisations start with a new set of values as the stimulus for culture change. However nice words do not change behaviour. It is better to start with the process above, which articulates the way we want to ‘do things around here’. The values that are needed to underpin the cultural vision will emerge from it. Some of them we may already have, and these need to be built on rather than changed per se. Some new ones may need to be developed but they will be the result of other changes. I worked with one organisation that came up with a set of five values, three of which were the complete opposite of the way they actually behaved. They were certainly desirable but were just not achievable unless there were radical changes in many other factors on the ‘map’.

This exercise will provide the new centrepoint of our cultural map. The change project owner then needs to examine which of the ‘levers’ on the map to pull. Extensive consultation is advisable before setting the change agenda. Typically we would go to the senior managers and ask them what this means for change. We can have a dialogue as follows:

- How would you score the current state of each of these statements?

- What behaviours do you see as those we must reinforce and those we must try to eliminate?

- What specifically does this mean in terms of ‘what we must do’ and ‘what we must not do’?

- If we match the systems and processes that operate in your area against this vision, how do they stand up? Do any need to change?

- Are changes in structure needed to facilitate this vision?

- Are new knowledge, skills and attitudes needed in your people? and

- What other barriers do you see to success (using the cultural map)?

Many organisations work on a cascading top down basis for such changes. However most of the real work is done at the bottom, ie at the front line. So at the same time this exercise should be done with front line teams who will undoubtedly see things that top management does not.

What about middle management? They are often actually seen as the real barriers to change, which may genuinely be desired by people at the top and at the bottom. Of course we should consult them – but last. We would then present them with the vision, and the outputs of the other consultations, and understand the difficulties they see in implementation.

At the end of all this we will have a very clear idea of what needs to be changed at the different levels in the organisation, and then be able to prioritise actions, taking people along with us because of their involvement in defining the change.

The template we have developed as the desired end state will provide an instrument for regular monitoring of progress. It should be given to all stakeholders so that we get both the external as well as the internal picture.

The role of leadership

A cultural change project is likely to be run by HR, with or without the help of consultants. But it will not work if the leadership team just leaves it there. The team has a fundamental contribution to make by:

- Constantly articulating the vision in practical terms;

- Role modelling all the desired behaviours;

- Seeking feedback from those around them on their behaviour;

- Reinforcing the desired behaviours in others by appropriate comment;

- Discouraging (if only by the disapproving word) undesirable behaviours;

- Making difficult decisions in a way that is consistent with the desired vision;

- Demanding and contributing to progress reports;

- Publicising progress; and

- Maintaining regular contact with the front line of the organisation.

Conclusion

No business strategy is complete without an examination of the culture that is needed to deliver it effectively.

Download PDF version:

About the author

Andrew Mayo is associate professor of human capital management at Middlesex Business School, and is president of the HR Society in the UK.

References

- G Johnson and K Scholes (eds.), Exploring Public Sector Strategy, Prentice Hall, 2001.

- J I Porras, and J C Collins, Built to Last, New York: Harper Business, 1994. A revised edition (1998) is available in the ICAEW Library.

- S Stuart, CEO succession: making the CEO succession making the right choices. A study of CEO transitions across four prominent European markets, 2011.

- C B Handy, Understanding Organizations, 3rd edition, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1985. The 4th edition is available in the ICAEW Library.

- E H Schein, Organizational Culture and Leadership, 3rd edition, Jossey-Bass, 1985-2005.

More support on business

Read our articles, eBooks, reports and guides on finance transformation

Finance transformation hubFinancial management eBooksCan't find what you're looking for?

The ICAEW Library can give you the right information from trustworthy, professional sources that aren't freely available online. Contact us for expert help with your enquiries and research.