What would you do if you had to choose between the fate of your friends and the demands of your enemies, while being captured and under duress by the Gestapo? That is the question we are forced to contemplate by the wartime story of Gilbert Maurice Norman.

An articled clerk in the run up to the Second World War, Norman is one of 475 souls recorded in ICAEW’s Roll of Honour, a hand-calligraphed book displayed in the Members’ Room of Chartered Accountants Hall to commemorate professionals who gave their lives in the conflict.

The circumstances that led Norman to his tragic end reveal a great deal about the intensely stressful highwire act of covert operations during the war – and the courage required to maintain it.

A cross-cultural fit

As previously explained in the article on John Franklyn Venner, in July 1940 the government launched the Special Operations Executive (SOE): a new branch of the covert world tasked with conducting acts of sabotage against German war efforts overseas.

Disdained by established secret service branches and the regular army for its focus on causing mayhem, this ‘Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’ was nonetheless a highly organised network of geographical Sections. And, as the article on Venner demonstrates, the SOE had a shrewd knack for recruiting top-quality personnel.

Born in St Cloud, France, in 1914, Gilbert Norman benefitted from a dual-culture background. Raised by English father Maurice Henry – a Paris-based Chartered Accountant – and French mother Lily, Norman was bilingual, being educated in both England and France.

In 1940, just a few months after the outbreak of the war, Norman joined the British Army. That November, he was commissioned into the Durham Light Infantry – but his dual heritage soon caught the attention of SOE talent spotters. Recruited for training, Norman was forbidden by strict secrecy rules to divulge that he had moved across to the agency.

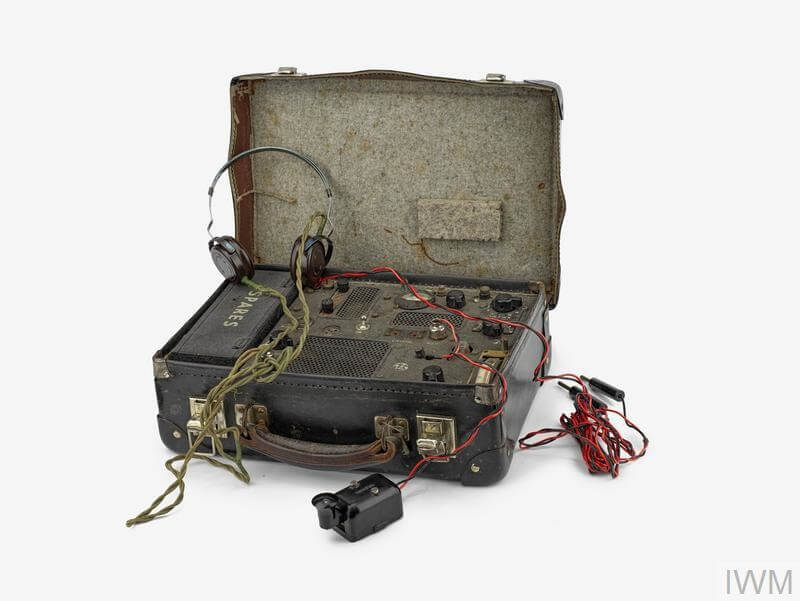

One of the most critical tasks that SOE handled was coordinating the movements of agents and supplies to sabotage hotspots. To do that, it needed superb wireless operators. In November 1942, Norman was parachuted into occupied France to man radio gear for the Prosper Network: a cell of SOE’s French Section, based in Paris.

At Prosper, Norman served under the network’s creator and leader Francis Suttill: another dual British-French national. A month after Norman’s arrival, co-operator Jack Agazarian – a Londoner of Armenian-French parentage – joined the fold.

Suspicions of treachery ignored

Operating a wireless was one of the most dangerous jobs an SOE agent could do. The average life expectancy after commencing the role was just six weeks.

Hours were punishingly long, and the workload relentless – but Norman quickly established a reputation for excellence. Liaising with contacts in London, he relayed progress reports on SOE activities, organised transport of incoming agents and requested air drops of money, equipment and other, vital supplies.

To maintain secrecy, operators used the poem code system, whereby words chosen at random from poems agreed upon by the London and Section heads formed the basis of Morse code encryption and decryption keys. And with enemy detector vans routinely on the prowl, operators were urged not to remain in any location for longer than 20 minutes – in practice, often a challenge.

In January 1943, a pivotal figure entered the fray. Born in 1909, French national Henri Déricourt had initially trained as a French Air Force pilot in 1930, but was working as a civilian pilot following the 1940 French surrender. Two years later, he fled to Britain – and eventually found his way into SOE.

Throughout his first few months at Prosper, Déricourt coordinated the arrival by air of at least 67 agents, including Noor Inayat Khan, the first female radio operator ever sent into occupied France. However, Déricourt – who Agazarian had long suspected of treachery, with his concerns rejected by SOE chiefs – was also in contact with German intelligence.

This set the stage for disaster.

"Over the margin"

On 23 June 1943, Norman was at a Prosper address pre-coding messages with fellow agent Andrée Borrel, when Gestapo men burst in and arrested them. The pair were taken to 84 Avenue Foch: the Paris headquarters of the SS intelligence wing - the Sicherheitsdienst (SD).

In short order, Suttill, too, was arrested – at which point, Prosper was effectively blown. Also taken to Avenue Foch, Suttill was tortured for days, while Norman and Borrel were subjected to intense questioning by SD wireless expert Dr Josef Goetz.

It is here that the story is caught in a crossfire of contesting accounts. But it is generally accepted that either Norman himself under duress, or Goetz acting on his information, used Norman’s radio to contact London. The established protocol was that Norman would add two agreed words to the front of the message to show that it was genuine. Under SOE rules, omitting these words should signal to London that an agent was in trouble. But the only response from London was to reprimand Norman for failing to include these words, revealing to the Germans that Norman had tried to mislead them.

According to historian M.R.D. Foot, London’s response as well as the SD deceiving Norman by implying he had been sent to France by a traitor based at SOE headquarters pushed Norman “over the margin of doubt and into practical co-operation” with the enemy. Accounts indicate that Norman yielded information to preserve the lives of his fellow agents – but the Germans never honoured their side of the bargain to spare the other agents’ lives.

While incarcerated at nearby Fresnes Prison, Norman was shot in the leg amid an escape attempt. After that, he was transferred to Austria’s brutal Mauthausen Concentration Camp, based around a quarry – from which prisoners were forced to carry large blocks of granite on their backs up 250 “stairs of death”. There, his condition swiftly worsened.

On 6 September 1944, Norman was executed by a method of hanging chosen to prolong his death.

In his 1966 book “SOE in France”, Foot argued that at the time of their arrest, Suttill and Norman were no longer “in a mood in which they could trust themselves to make calm and considered judgements”. While their treatment at Avenue Foch had likely extracted valuable information, Foot wrote, “no one should condemn him for doing so who does not know he could have done better, under a similar strain, himself”.

Gilbert's father, who was himself honoured with an MBE for his civilian work during the Second World War as Deputy Director of Costings at the Ministry of Food, fought for recognition for him after his death. Today, Gilbert Norman is commemorated on a memorial at Brookwood Military Cemetery which recognises the SOE personnel who died in occupied Europe and who have no known grave.