Graham Gardner explores five elements that form the foundation of effective substantive analytical procedures.

Substantive analytical procedures (SAPs) are a useful audit test. If executed properly, they can provide good audit evidence and efficient use of time. However, when executed poorly, they may lead to more harm than good (for example, by not providing the extent of evidence the auditor thought they were getting).

Following a structured approach to completing a SAP can help reduce the execution risk and ensure that the procedure is able to stand up to regulatory scrutiny.

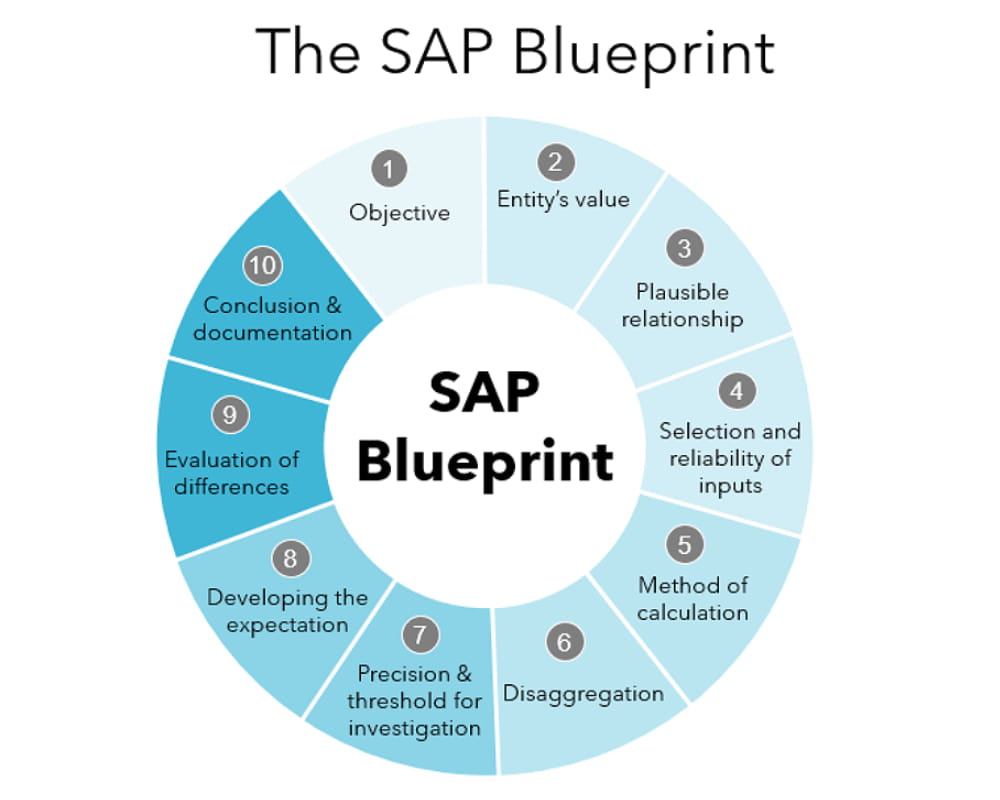

A recent ICAEW webinar presented a 10-part SAP blueprint covering its various components. In the first of two articles, Graham Gardner considers the first five elements.

1. Objective

First, we need a clear understanding of our audit objective. Remember that a SAP is performed in response to an assessed risk of material misstatement, so we should already understand what risk (at the assertion level) we are trying to respond to at the point of design.

Highlighting a couple of points from the definition of an analytical procedure provided by ISA 520 may help us set the context for the procedure. The ISA says an analytical procedure is the “evaluation of financial information through analysis of plausible relationships among both financial and non-financial data”. The term plausible relationship means that there is a logical basis for determining the value of an account other than by looking directly at what is in the financial records. In other words, the balance is inherently predictable.

In essence, what we’re doing here is making a prediction about what the value of an account should be and then assessing whether the actual value matches that prediction. Clearly the accuracy of the prediction we’re able to make will vary wildly by account and by how much effort we put into modelling this, which leads us to the concept of precision. How precise does the prediction need to be, and how precise can it be?

How precise the prediction needs to be is determined by the type of procedure we are performing. Analytical procedures include:

- planning analytics (ISA 315);

- substantive analytical procedures (ISA 520); and

- final analytics (ISA 520).

Each of these is performed for different purposes and will, therefore, require different levels of precision. Planning and final analytics are examples of risk assessment procedures, which are “designed and performed to identify and assess the risks of material misstatement”. In other words, they tell us something about the likelihood and magnitude of misstatement in the account, but not whether the value in the account is actually correct.

Substantive procedures, such as SAPs, are “designed to detect material misstatements”. In other words, they need to be capable of providing evidence of misstatement, or the absence thereof.

So the level of precision (or predictability) we need in a SAP far outpaces that which is needed for a planning (or final) analytic. This is why attempting to claim substantive evidence based on a simple year-on-year movement is not appropriate. Why should sales this year be the same as sales last year? The actual sales made are driven by various market forces that differ year-on-year, as well as the number of people who happen to have done business with the entity in each year. Sales, and other account values, are almost never flat in any company – there’s always a level of variability year-on-year.

It may be that, based on our understanding of the market and how the entity fits within it, we expect that sales should roughly be similar to the previous year. In this case, a 50% jump in sales revenue would make us raise our eyebrows. This would now be pointing to some element of change within the entity or market conditions that we weren’t aware of, so we’re now talking about change as an inherent risk factor. We ask ourselves “why has the sales figure changed so much year-on-year – has something changed in the business? Have sales been recorded incorrectly?” This is good risk assessment. But none of that tells us what value sales should be in the current year. There simply is no plausible or sufficiently predictable relationship between the two.

2. Entity’s value

The next element is determining the value of the account balance you are testing and understanding how it is made up. As with any substantive test, the value of the account as shown in the general ledger isn’t necessarily the value being audited as part of the specific procedure. In the context of SAPs, we may be able to predict the gross sales value, but this does not take into account discounts or returns. Therefore, we would need to ensure we compared our prediction to the gross sales per the ledger, rather than net.

This requires that we:

- obtain an understanding of what makes up the account and how the final value feeding into the financial statements is determined;

- consider whether we are testing the entire account, or a part thereof. We’ll cover this further in the section on disaggregation in the second article; and

- ultimately, we need to define the value being audited as part of the SAP.

3. Plausible relationship

Next, we need to define the relationship being used to predict the value of the account balance. We have already discussed much of this element. To re-iterate:

- the relationship must be sufficiently plausible and predictable to allow substantive evidence to be obtained;

- it must be stable enough to form the basis for a reliable expectation. Just because the relationship held in a prior period doesn’t mean that is still the case;

- we should consider whether there are other factors that may weaken the predictability of the relationship, for example outlier transactions; and

- it must ultimately allow the development of a sufficiently precise expectation.

4. Selection and reliability of inputs

Let’s now address the inputs to the SAP. The most critical point to note here is that the SAP must provide a prediction that is independent of the entity’s financial records. We need to be very careful that we’re not simply reperforming the entity’s calculation or reconciling the entity’s internal records.

We therefore need to ensure that the inputs we are using to build our expectation are independent of the entity’s financial processes. Normally you would need at least two inputs for a SAP. At least one of these has to be independent to avoid being a simple recalculation. Consider the example of a payroll SAP based on headcount. This procedure uses an established average pay rate, adjusted for in-year pay rises, and the total number of employees. The figure for the number of employees is sourced from HR and is not used by the entity to calculate their total payroll cost. It is therefore an independent input. The more independent inputs we can use, the more persuasive the SAP is likely to be.

In addition, inputs from sources external to the entity are likely to be more persuasive than sources inside the entity. We should therefore use external inputs wherever possible.

Finally, regardless of where the information making up our inputs has been sourced from, we need to ensure we test its reliability. This is critical to producing a good SAP – remember the concept of garbage in, garbage out.

5. Method of calculation

Element five in the blueprint is the method of calculation of the prediction. There may be many ways to perform a SAP, ranging from the use of simplistic relationships, such as the payroll SAP based on headcount, to far more sophisticated models that apply forms of regression analysis or data science.

Whichever method is used, it is important that we keep our focus on the plausible relationship that underpins our prediction. It’s possible to overengineer these; a more complex SAP is not necessarily more persuasive.

When using particularly complex models, it’s a good idea to perform some form of back-testing using the previous year’s data, or a dry-run using current year interim data. This will help to iron out any faults in our assumptions or application of the model early in the audit process.

A high-quality SAP is won or lost at the design stage. Without a clearly defined objective, a sufficiently plausible relationship, reliable and independent inputs, and an appropriate method of calculation, the procedure is unlikely to generate meaningful audit evidence – regardless of how well it is documented or reviewed.

By taking the time upfront to work through these design considerations in a structured way, engagement teams significantly reduce execution risk and place themselves in a much stronger position when it comes to evaluating results and drawing conclusions.

In the next article, we will focus on how a well-designed SAP should be executed, refined and evaluated in practice.

Graham Gardner, Audit Partner and Head of Audit Quality, Kreston Reeves