Driving on the left came naturally to Swedes – but then they couldn’t do it any more

On 2 September, 1967, Swedes drove on the left side of the road, as always. The next morning, they switched sides – in a move that was, without a doubt, one of the best examples of a change management operation.

The task was massive, as nothing comes much larger than switching a whole country from left- to right-hand driving. Sweden had been a left-hand drive culture since about 1736. (Yes, traffic laws governed horse riders, too.) However, its neighbours, including Norway, Denmark and Finland, drove on the right. In defiance of the opposite-steering-wheel rule, about 90% of Swedes drove left-hand drive vehicles (due to the fact that Swedish manufacturers made cars mainly for the export market). With drivers positioned near the side of the road rather than near oncoming traffic, limited visibility led to many head-on collisions. And drivers crossing into Sweden got into accidents because of their unfamiliarity with its traffic protocols.

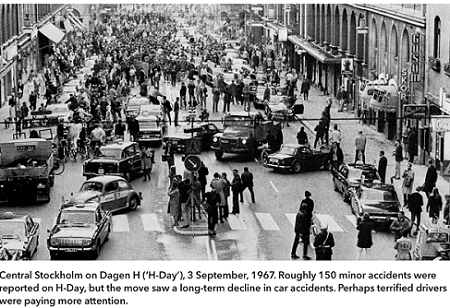

Despite a 1955 referendum, in which 83% of the population voted to keep driving on the left, the Swedish government decided it had to act. And so, in 1963 it mandated that the move to right-hand traffic flow would happen in 1967. Four years to get it right. And so began one of the world’s largest change management programmes, leading up to 3 September 1967 – aka H-day (the H came from ‘Högertrafik’ the Swedish word for ‘right traffic’).

It was an incredibly complicated undertaking. Traffic lights had to be reversed. Some 360,000 road signs had to be switched. Intersections had to be redesigned and reshaped, lines on the road repainted, bus stops moved, trams reconfigured. And that’s before you start to consider the joys of one-way streets. Or the practicalities involved.

Like the fact that every intersection was equipped with an extra set of poles and traffic signals wrapped in black plastic which were then simultaneously removed by an army of workers. Similarly, a parallel set of lines were painted on the roads with white paint, then covered with black tape ready for that ultimate moment of synchronicity.

The communication strategy was impressive. Not only was the day named, but it also got its own logo, which appeared on everything from milk cartons to underwear. There was a televised song contest where the winning tune was ‘Håll dig till höger, Svensson’ (‘Keep to the right, Svensson’) by The Telstars. The Swedish government even distributed gloves – one black, one red – as a reminder to drivers.

On H-day at 04:50 crowds of people gathered to watch as all vehicles on the road were instructed to come to a halt, move carefully to the other side of the road and wait. At the stroke of 05:00, following a radio countdown, an announcement was made over the radio ‘Sweden now has right-hand driving.’ And so, it did. Accidents dropped in the following months, in part because of improved vision while passing.

When you consider that this change was orchestrated without the communication tools we take for granted today, I say: respect to the Swedes.

Aside from that technology gap, the approach hasn’t really changed that much. My company has just finished helping a global business undertake a major transformation programme using some of the very same tools:

- a creative platform consisting of a name, idea and distinctive identity;

- a set of simple core messages implemented coherently across a range of materials and channels; and

- innovative and poignant behavioural cues and reinforcements to help make that change happen.

… But we didn’t make a song.

Stand on the right on the tube escalators – except when we tell you not to, said TfL at Holborn

It’s a perilous thing to try and change the routine of a commuter, but a while back London Underground (part of Transport for London) attempted to do this at Holborn station.

The goal was to get all emerging passengers to stand on both sides of the ‘up’ escalators to exit the station. Yet on all other escalators on the London Underground network, people are encouraged to walk on the left, stand on the right. This change to the usual routine was a disruptive challenge to an accepted, deeply engrained and almost automatic behaviour – in other words it was like herding cats.

As behavioural change programmes go, it was relatively straightforward to define and comprehend. But like many similar initiatives, the associated communication challenge required a significant investment of resources and needs to address a range of issues.

A wide range of channels were used along with some creative messaging. At the base of the escalator an incredibly polite, yet repetitive, hologram implored users to follow the new standing rules. Just before the escalator there was a floor-based poster and on each step were some stickered footprints. Every few metres to the side there were also small digital screens carrying a set of key messages, and a PA system delivered a short recorded message. So, within a metre of approaching the escalator, and for the next 30 seconds or so, it’s pretty much a captive audience being subjected to all of the above on a daily basis. Headphones and wandering thoughts aside, there is comprehensive coverage to reinforce a very simple call to action: stand on both sides.

And yet, the cats didn’t herd like they were supposed to do. It seems that, while some travellers may just follow instructions when in the herd/commute mode, it obviously doesn’t work for everyone.

My own view on the lack of success was that it might just be because there was little explanation as to why people were being asked to change the habits of a lifetime. There were a couple of clues as to the rationale, but somewhat bizarrely the first appears only after you leave the escalator, after the experience. At the top of the escalator, in a single, very formal, easy-to-miss poster was a partial explanation that advised that there was a test underway to help reduce congestion. The second, but only rarely used, was from someone in the station sharing that information over the PA system.

It turns out that a fuller explanation was to be found in the media. This was in fact a second test to address congestion, an earlier test having provided evidence of the counter-intuitive notion that standing still on both sides of the escalator speeded up exit times.

Digging a bit deeper into the media coverage revealed that the imploring messages were developed by the behavioural science department at the London School of Economics – and that they were testing a range of messages from direct imperatives to those that will ‘play on words about standing’, aka puns galore.

The first experiment involved extra staff in place with megaphones for three weeks. According to one report, though, it saw a return to existing behaviour under a week later. This later and longer trial was to test if commuters can be influenced by just signage and information.

Having read the media coverage, I now understood and appreciated the effort – and the potential benefit – to both myself and my fellow commuters. And this changed my personal experience of those communications – they were now playing a fundamentally different role for me. They were behavioural cues to remind me, because they had context. The important foundation of awareness and understanding had been established. And that should have helped the nudge needed in attitude and behaviour to make the shift from compliance to commitment. The big problem was … how many other commuters had read the wider media surrounding the experiment? How many others understand the rationale?

Without the ‘why’ being better embedded and appropriately incorporated in the commuter experience, the dawn chorus of harassed harrumphs and tolerating tuts persisted. And the cats remained unconvinced, unmoved and unwilling to change.

About the author

Phil Morley is director of employee engagement at MerchantCantos.

Related resources

More support on business

Read our articles, eBooks, reports and guides on finance transformation

Finance transformation hubFinancial management eBooks