MAX (and MIN) may be familiar to many Excel users, but it is still probably worth performing a recap (I haven’t discussed these functions for nine years!). As a model auditor, I do see errors made regularly due to misunderstandings made with how these two similar functions actually work.

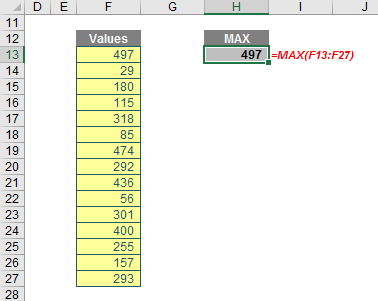

MAX calculates the maximum value in a range, whilst MIN calculates the minimum value in a range. To avoid repetition, I will only consider MAX in the first part of this article, but the points made here are equally valid for MIN.

It is very simple to use:

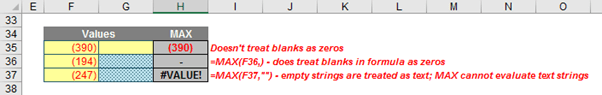

The problem is modellers do frequently make mistakes with MAX (and MIN):

These examples highlight that you should be careful with using blanks both in the ranges and in the formulae themselves. Regular readers will notice I often omit zeros in my formulae but with MAX (and MIN) I will often take care to explicitly use zeros.

The MAX function has the following syntax:

MAX(number1, [number2, …])

Its arguments are relatively straightforward to follow:

- number1, number2, …: number1 is required, but subsequent numbers are optional

- you may have up to 255 arguments in order to find the maximum value.

It should be noted that:

- arguments may be numbers, or names, arrays or references that contain numbers

- logical values and text representations of numbers that you type directly into the list of arguments are counted

- if an argument is an array or reference, only numbers in that array or reference are used; empty cells, logical values or text in the array or reference are ignored

- if the arguments contain no numbers, MAX returns zero [0]

- arguments that are error values or text that cannot be translated into numbers cause errors

- if you want to include logical values and text representations of numbers in a reference as part of the calculation, use the MAXA function instead.

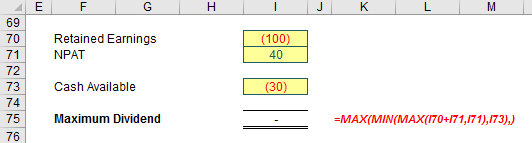

There is a highly relevant finance example combining MAX and MIN functions, whereby they calculate the maximum dividend allowable for a particular period. This is not the calculation for actually deciding what the dividend itself should be; it is simply evaluating the maximum dividend. The example below may be found in the attached Excel file.

As an aside, dividends are often calculated as a proportion of some profit measure (typically Net Profit After Tax [NPAT]) in financial models, e.g. 20% x NPAT. Unfortunately, profits – even in forecast financial models – tend to not increase smoothly, which leads to volatile dividend profiles. Shareholders do not take kindly to unpredictable dividend streams and thus share prices tend to be discounted in such circumstances. Ironically, this action reduces shareholder value, which in turn reduces funds available, which thus reduces investment opportunities and hence hurts shareholder value, which again reduces profits, ad lib to nauseum.

If real life were to mirror this computation, things could turn nasty very quickly. Not that many modellers do this, but it is better to agree a dividend and then grow it by a predictable percentage each year instead. But that’s a separate decision for you and your colleagues to make and not within the scope of this article.

Returning to our example, dividends may only be paid out of what are known as distributable reserves (this is a bit of an oxymoron as dividends are also known as distributions). Revaluation reserves, share premium accounts and capital redemption reserves are all non-distributable. Typically, dividends may only be paid out of the current year’s Net Profit After Tax (NPAT) and the aggregation of all previous year’s profits after past distributions, Retained Earnings. Dividends may not make the Balance Sheet’s Total Equity become negative either. This is one indicator of insolvency and this sort of distribution is illegal in most territories. Given non-distributable reserves may not become negative allow me to concentrate simply on NPAT and Retained Earnings here.

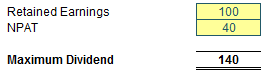

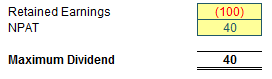

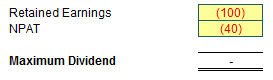

To derive the maximum dividend allowable, let me consider some scenarios. Let’s imagine the following scenario:

If Retained Earnings and NPAT are both positive, then the maximum dividend allowed is the sum of the two.

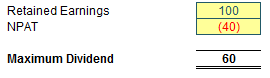

If NPAT is negative, but Retained Earnings are positive and exceed the NPAT figure, then the maximum dividend allowed is the net of the two figures. Should the net be negative, no dividend is allowed.

Here is the one that often surprises people. If Retained Earnings is negative but NPAT is positive, regardless of whether the net is positive or negative, the maximum dividend allowed is the NPAT amount. This may seem incomprehensible upon first thought, but it is typically dependent upon two conditions:

- The company’s auditors must sign off on it. This is to ensure the company is still seen to be a going concern (i.e. it can still continue to operate and trade its way out of any short-term difficulties).

- The shareholders must vote for it. That will be a tough condition to pass, I’m sure.

Allow me to explain. Dividends cannot be paid if the company is insolvent. The auditors check to see whether the company can “afford” it for other reasons. But if you don’t allow this scenario how would anyone ever attract share capital for a start-up company? A new company may have to provide for certain factors which may never come to fruition. A large non-current asset may have to be written off as not fit for purpose if a company’s strategy changes without any cash consequence. Is it acceptable that shareholders have to wait 10 years for the Retained Earnings losses to be covered even if the business is hugely profitable in the meantime? No, and this is precisely why this is the rule in many territories.

The next scenario is more obvious:

With both a negative NPAT and Retained Earnings, there is no leeway now. These scenarios seem to suggest the following formula:

=MAX(NPAT + Retained Earnings, NPAT, 0)

This allows for the above scenarios. The check to ensure that the value is non-negative (i.e. the inclusion of zero in the MAX formula) is so that shareholders do not get asked to pay a dividend to the company. I can’t imagine that would go down too well.

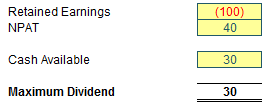

We are not done yet though. Let’s go back to the penultimate scenario but now consider the cash position as well:

Here, the Cash Available is the total amount of cash available to pay the dividend. Technically, this includes any cash reserves built up over time, but many companies only consider the cash position for the period the dividend relates to (this ensures you do not run out of “rainy day” funds over time). This seems to suggest the formula:

=MIN(MAX(NPAT + Retained Earnings, NPAT, 0), Cash Available)

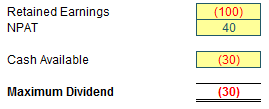

Let me just check with slightly revised numbers:

In this scenario, the company is overdrawn. The formula is not quite right. Here, this company is going to be asking for money again from its shareholders. Not a good idea. This leads to the slightly revised – and finally correct – formula:

Maximum Dividend = MAX(MIN(MAX(NPAT + Retained Earnings, NPAT), Cash Available), 0)

And there you have the delightful MAX(MIN(MAX)) formula. It may not be the most immediately intuitive formula in the world, but the point is, it gives the right number and uses two of the most basic (and oft neglected) functions in Excel to assist.

Archive and Knowledge Base

This archive of Excel Community content from the ION platform will allow you to read the content of the articles but the functionality on the pages is limited. The ION search box, tags and navigation buttons on the archived pages will not work. Pages will load more slowly than a live website. You may be able to follow links to other articles but if this does not work, please return to the archive search. You can also search our Knowledge Base for access to all articles, new and archived, organised by topic.