What is public debt?

Public debt, also known as the ‘national debt’, is the accumulated amounts of borrowing that the government, and other public sector bodies, owe to the private sector and foreign governments.

It has been built up over several centuries as successive governments have borrowed to finance the deficit and meet other cash requirements.

There are various ways of measuring debt, but the UK government prefers to use:

- public sector net debt (PSND or ‘headline debt’), and

- and public sector net financial liabilities (PSNFL or ‘financial debt’ or sometimes ‘persnuffle’).

In each case, these are net numbers, calculated by deducting cash and other financial assets from the gross amounts owed.

Public sector net debt

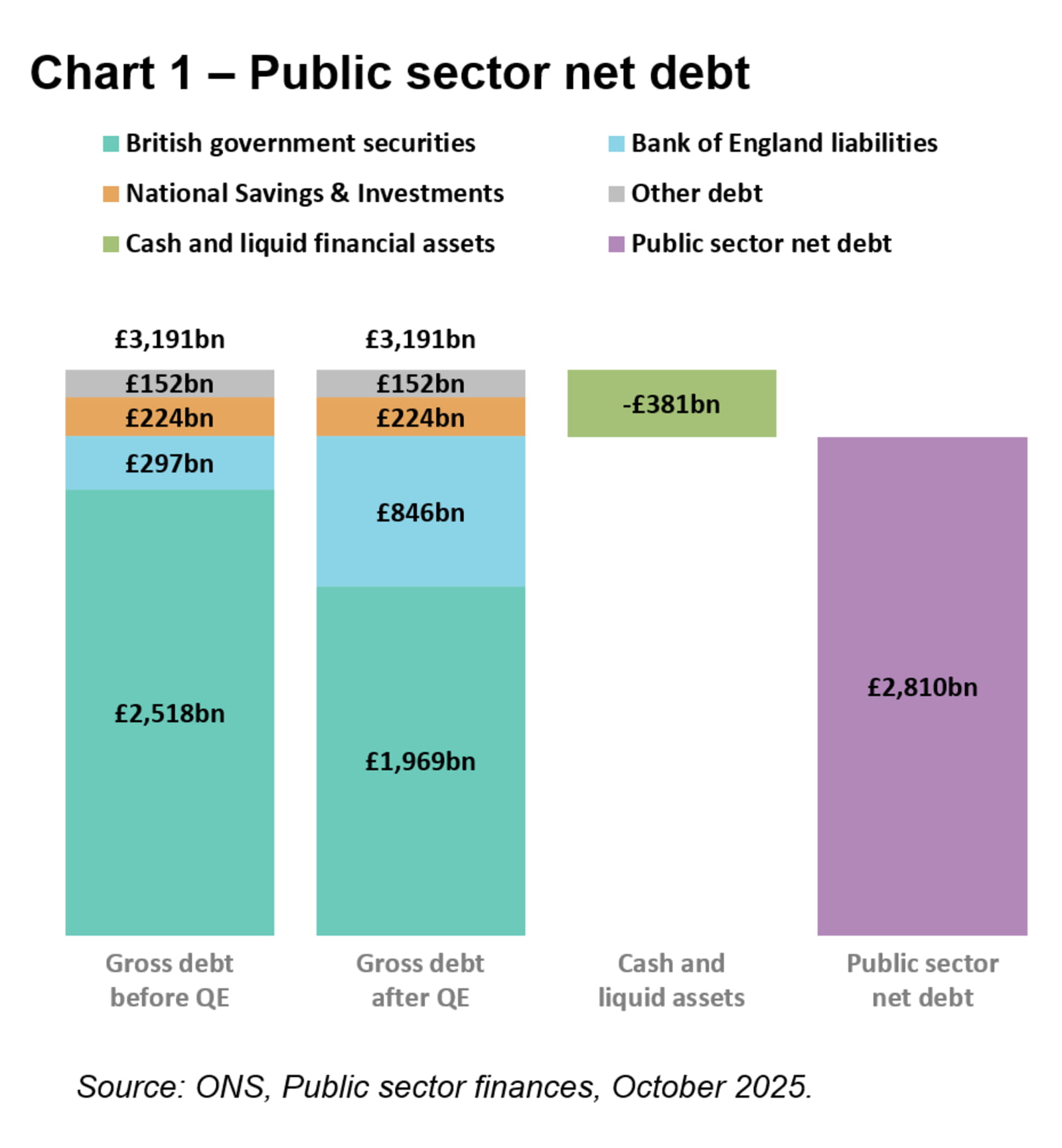

Headline debt was equal to £2,810bn on 31 March 2025, equivalent to 93.6% of GDP, meaning it is not far off being equal to the size of the overall UK economy.

Most government borrowing is raised by HM Treasury’s Debt Management Office through the issue of British government securities to institutional investors at regular auctions.

On 31 March 2025, these securities comprised around:

- £1,840bn of fixed-interest gilts that have an average maturity of around 13 years,

- approximately £600bn of retail-price-inflation-index-linked gilts with an average maturity of around 18 years, and

- £75bn in treasury bills that mature and rollover within six months or less.

The Bank of England owed £846bn to its depositors on 31 March 2025, but as it owns £549bn of gilts as part of its quantitative easing (QE) operations to support the economy it is typically reported as a net amount of £297bn.

An alternate presentation is also shown in Chart 1, with the £549bn in cross holdings netted off British government securities to show the amount owed to external investors of £1,969bn.

National Savings & Investments (NS&I) is a government-owned retail bank that takes in deposits directly from the public, with £224bn owed on 31 March 2025 to the holders of premium bonds and savings certificates.

Other debt includes £29bn owed by Network Rail, a net £17bn by local government (£136bn total less £119bn owed to central government), and £106bn in loans and other forms of debt.

The total debt of £3,191bn is before deducting £381bn of cash and other liquid financial assets (including £131bn held by the Bank of England) to give net public debt of £2,810bn on 31 March 2025.

This is equivalent to around £42,000 per person for each of the 69.4 million people living in the UK in March 2025.

How does public debt affect people and businesses?

Public debt attracts interest, which means that there is less available for spending on public services. This was less of an issue when we had ultra-low interest rates, but higher borrowing costs combined with high levels of debt is much more of a problem.

A high level of debt also makes the government more reliant on the goodwill of investors of 'the kindness of strangers', especially as it must also refinance a substantial amount of existing debt as it matures each year.

For example, the government plans to borrow £327bn in the current financial year (2025/26), comprising:

- £168bn to refinance the existing debt as it fall due for repayment;

- £138 to finance the deficit (the shortfall between receipts and public spending), and

- £21bn to fund working capital and other cash requirements.

With debt now close to 95% of GDP, the situation is more difficult. There is no benchmark amount for how high debt can go before losing the confidence of debt investors, so in theory the UK could borrow even more either as a policy choice or in response to a future economic shock so that debt goes above 100% of GDP.

However, higher debt brings with it heightened risks of an adverse market event, as happened following the mini-Budget in October 2022 that led to the resignation of then prime minister Liz Truss.

The challenges in controlling public debt

There are two principal ways to control public debt. The first is to raise taxes or cut spending to reduce the deficit, slowing the rate at which debt increases.

Generating a surplus would allow debt to be repaid, which has happened only three times in the last fifty years in the UK. Apart from Germany prior to the pandemic, few countries have been able to achieve this.

The second is to grow the economy so that GDP rises proportionately faster than the level of debt. This results in a falling debt-to-GDP ratio, which is what government ministers mean when they talk about 'bringing down debt'.

The government’s plan set out in the 2025 Budget is to constrain public spending and raise taxes so that the deficit falls, while also relying on economic growth to generate more in tax receipts too.

What is the outlook for public debt?

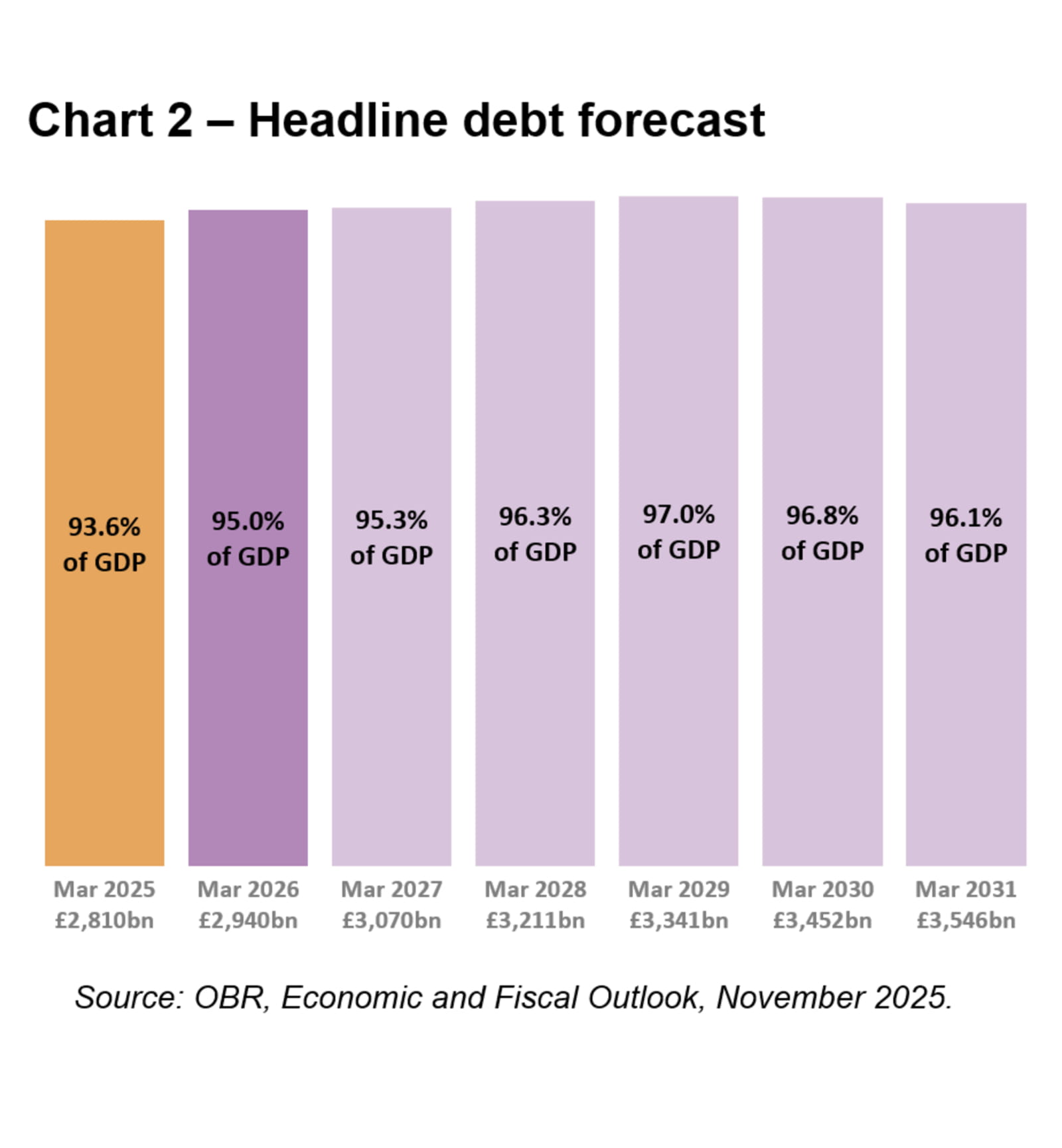

The Office for Budget Responsibility has forecast that headline debt will peak at 97.0% of GDP in March 2029 (see Chart 2) and then gradually fall to 96.1% of GDP by March 2031.

One flaw in this measure of public debt is that while it nets off liquid financial assets, such as cash, it does not net off other financial assets such as lending or equity investments made by the British Business Bank, the National Wealth Fund or GB Energy, for example.

As a consequence, the use of this measure for the fiscal rules had a disincentive effect for such investments, even though most of them are expected to be repaid or eventually disposed of at a profit.

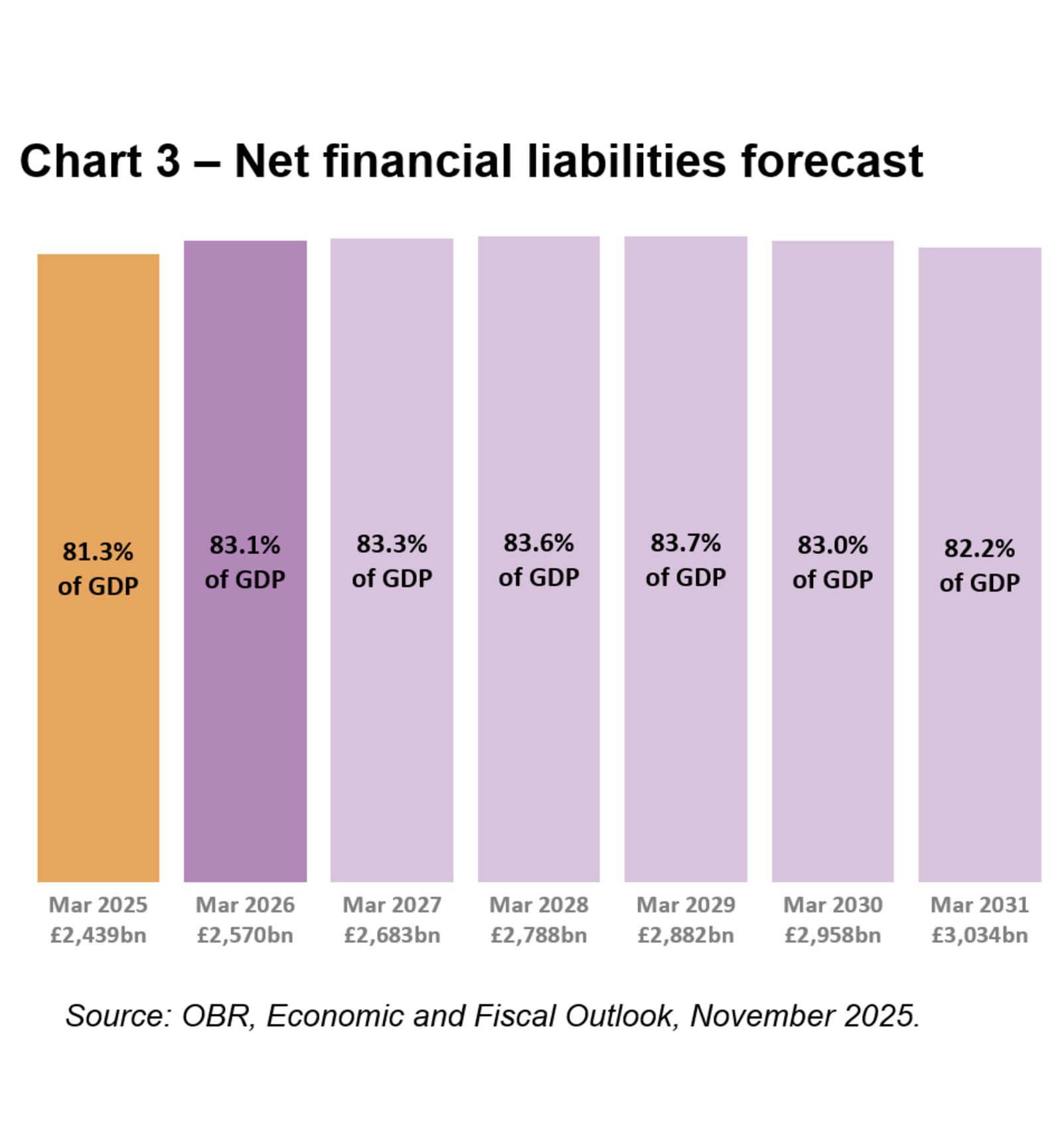

The Chancellor has therefore selected an alternative measure of public debt to use for her fiscal rule: public sector net financial liabilities (PSNFL or ‘persnuffle’) that makes it easier to invest.

As Chart 3 illustrates, PSNFL is lower than public sector net debt as, although it incorporates non-debt financial liabilities in addition, the amount of non-liquid financial assets netted off is greater.

In the 2025 Budget, the Chancellor announced that she had met her secondary fiscal rule for net financial liabilities as a share of GDP to be falling in the fourth year of the fiscal forecast – from a projected 83.7% on 31 March 2029 to a projected 83.0% on 31 March 2030, providing her with £24bn in headroom against this fiscal rule.

What are the long-term prospects for public debt?

Public sector net debt (and public sector net financial liabilities) are expected to fall as a share of GDP for the next few years following the above forecasts, before starting to rise again over the following 40 years to a potential 274% of GDP (or more) by 2073/74.

This long-term fiscal projection, as calculated by the OBR in its fiscal risks and sustainability report, reflects the increasing costs of pensions, health and social care as more people live longer and a reduced proportion of working age taxpayers from a falling birth rate and lower levels of inward migration than we have recently experienced.

In reality, public debt will not rise as high as this as future governments will choose to raise taxes, cut spending, and/or attempt to generate higher levels of economic growth to prevent this scenario occurring.

ICAEW has called on successive governments to develop a long-term strategy to put the public finances onto a sustainable path.

ICAEW on the Budget