The government is keen to encourage business investment and innovation, but the application of the tax rules can be less than clear. Technical Editor Lindsey Wicks explains.

The government is keen to encourage private business investment. It also wants to encourage innovation. This, it hopes, will boost productivity and help with levelling up to end geographic inequalities.

In the past couple of years, there has been a flurry of government announcements aimed at boosting capital investment – in particular as part of the shift towards decarbonising the UK’s energy supply. These announcements include:

- The Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolutionon 18 November 2020;

- Net Zero Strategy: Build Back Greener on 19 October 2021; and

- British Energy Security Strategy on 7 April 2022.

Each of these builds upon the previous paper. While significant government investment is planned, the aim is that this will be more than matched by private sector investment. The original 10-point plan set the ambition that the private sector investment would be as much as three times that of the government.

Encouraging business investment

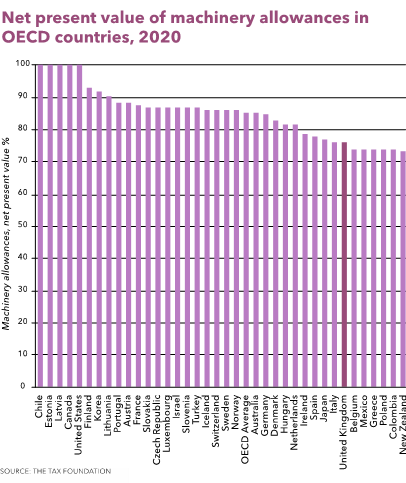

In his Spring Statement, Chancellor Rishi Sunak flagged that capital investment by UK businesses is considerably lower than the OECD average of 14%. He also acknowledged that once the super deduction ends, the UK’s tax treatment for capital investment will be far less generous than other advanced economies (see chart below).

To address this, the Spring Statement announced a series of potential policy changes to the UK’s existing capital allowances regime, which the government will consider ahead of the end of the current super deduction in April 2023. These are not mutually exclusive and may be adopted in combination. The government’s aim is to achieve a balance between simplicity, generosity and impact on investment. The table (see below) sets out the potential options and indicative costings.

Option |

Indicative cost |

|---|---|

Increase the permanent level of the annual investment allowance (e.g, £500,00). |

At its peak, this could cost £1bn in a single year. |

Increasing written down allowances (WDAs) for main and special rate assets from the current levels of 18% and 6% to 20% and 8% respectively. |

At its peak, this could cost £2bn in a single year. |

Introduce a first-year allowance for main and special rate assets where businesses can deduct, for example, 40% and 13% in the first year, with the remaining expenditure written down at standard WDA rates. |

At its peak, this could cost £3bn in a single year. |

Introduce an additional first-year allowance, to bring the overall amount that can be claimed to greater than 100% of the initial cost. |

At its peak, an additional allowance of 20% could cost over £4bn in a single year. |

Introduce full expensing, to allow businesses to write off the costs of qualifying investment in one go. |

At its peak, this could cost over £11bn in a single year. |

This was followed by a policy paper from HM Treasury on 9 May inviting views on potential reforms by 1 July. As well as exploring the options opposite, the government is keen to understand:

- how businesses make investment decisions and the relative importance of capital allowances in this decision-making process;

- how has the super-deduction affected the investment decisions of companies ahead of it ending in 2023; and

- what more could the capital allowances regime do to support business investment.

Rates v certainty

Changing the rates is one thing, but if the government is looking to attract significant private sector investment in these projects, do the underlying rules need reviewing?

Recent case law demonstrates the number of major projects that end up being appealed at the tribunal and beyond because of disputes between HMRC and the taxpayer concerning whether expenditure qualifies for capital allowances.

The government is keen to encourage innovation as part of the journey to net zero. However, innovation (or doing something differently) often causes the dispute. Major projects also involve a lot of pre-planning and investigative studies, but these costs can fall into a tax black hole (a ‘tax nothing’).

Let’s look at some of the issues.

Studies and project management costs

Gunfleet Sands Ltd & Ors v HMRC [2022] UKFTT 35 (TC)

Given that the government is trying to encourage a green industrial revolution, it seems somewhat ironic that this case involves offshore wind farms. In particular, the case concerned the extent to which capital allowances are available for the considerable expenditure (almost £48m) incurred on studies and project management in relation to the offshore wind farms concerned.

HMRC argued that some of the expenditure on the studies was too remote from being part of the expenditure on plant. It was not on the provision of the generation assets (wind turbines, etc) individually or as a whole and therefore did not qualify for capital allowances.

The First-tier Tribunal (FTT) determined that some of the studies could qualify for allowances, but only if they impacted the design or construction in a way that affected the operational ability or safety and effectiveness of the windfarms.

The FTT also confirmed that those studies that did not qualify for capital allowances cannot qualify for a revenue deduction. This is because the expenditure is on items of a capital nature, even if the expenditure does not fit within the highly specific wording that appears in the capital allowances legislation.

The FTT observed: “This is an example of a tax nothing of which there are many examples in the tax code. It is an item of expenditure for which neither a revenue deduction nor capital allowances are available. Simply because it falls out of the arms of the capital allowance legislation does not mean that it falls into the lap of the trading deduction legislation.”

Complexity, interplay of the rules and (lack of) definitions

HMRC v SSE Generation Ltd [2021] EWCA Civ 105

This is another tax case concerning ‘green’ electricity generation. The case tested the extent to which expenditure on Glendoe hydroelectric power station near Loch Ness qualifies for plant and machinery allowances.

SSE had claimed allowances on £260m expenditure, but HMRC only accepted some £34m. Approximately £227m of allowances were in dispute and the case has been argued as far as the Court of Appeal.

The disputed expenditure concerned whether the significant building and structural elements associated with the provision and installation of the plant were also eligible for plant and machinery allowances. HMRC accepted that the expenditure met the general rule in s11(4), Capital Allowances Act 2001 (CAA 2001) of being qualifying expenditure on plant or machinery wholly or partly incurred for the purpose of a qualifying activity. However, the issue is whether the items were then struck out by one of the exceptions. The case covers the interplay between s22(1)(a) and (b), CAA 2001 and looks at the meaning of structures such as aqueducts and tunnels.

The courts determined that SSE was entitled to claim plant and machinery allowances on the majority of the disputed items.

It is interesting to note that the capital allowances rules do not contain positive definitions of ‘plant or machinery’ or ‘building or structure’, although ss21-23 were introduced in 1994 to try to draw a distinction between the two. The recent Upper Tribunal (UT) decision in Urenco Chemplants Ltd and Anor v HMRC [2022] UKUT 22 (TCC)) – a case involving £192m of disputed expenditure on a facility to process and make safe uranium by-products in the nuclear industry – observes:

“The subsequent legislation in this area highlights the difficulty of drawing such a line. Sands shift, not only because issues will arise which had not been specifically dealt with by case law at the time the line was drawn (in 1994) but because assets such as those in this appeal were not contemplated at that time … While the background to the code in sections 21 to 23 is in principle of assistance to us in construing the meaning of ‘building’, in that case law guidance prior to 1994 would help to inform that construction, in practice there is almost no specific guidance available on that issue, and in any event we must determine it in relation to novel and unusual assets.”

HMRC’s approach to the plant and building distinction

May v HMRC [2019] UKFTT 0032 (TC)

Crop production is seasonal. If we want to reduce reliance on overseas produce, we need to be able to store UK-farmed crops for longer. May concerned whether a horizontal grain silo was a silo and could therefore qualify for plant and machinery allowances. Even though the expenditure on the construction of the facility could fall within the general rule in s11(4), of being qualifying expenditure on plant or machinery wholly or partly incurred for the purpose of a qualifying activity, as it was a building it fell within the exceptions in s21 unless it was a silo provided for temporary storage.

HMRC argued that storage of grain for nine or 10 months was not temporary and that the building was not plant. The FTT disagreed and determined that storage was temporary, and that the facility as a whole was plant.

One of the expert witnesses had worked for HMRC as a capital allowances technical specialist until 2015. According to the case report: “Internally within HMRC he expressed the view that there was merit to the Appellant’s claim, but he produced a report stating that the expenditure did not qualify because he was told that it was HMRC policy to ‘hold the line’ that such structures did not qualify.”

As this was an FTT decision, it is only binding on the parties. In 2021, a similar case was appealed to the FTT – this time involving a warehouse to provide a controlled environment for potato storage for the manufacture of crisps (JRO Griffiths Ltd v HMRC [2021] UKFTT 257 (TC)). Once again, the FTT decided that the warehouse was plant and that it didn’t fall within the buildings exclusion as it was a silo for temporary storage and also a cold store.

Can we improve the rules?

The cases above highlight that the differential between rates for plant and machinery and structures and buildings will always lead to challenges over what side of the line the expenditure falls. Do we have to resign ourselves to the fact that, as the UT put it in Urenco, it will always be for the courts to determine what side of the line the expenditure falls where an asset is novel and unusual? On the one hand, the government wants the UK to be a hotbed for innovation, but on the other hand, the tax rules mean that innovative investment projects will be challenged.

Also, in a system where we now allow relief for expenditure on structures and buildings, is it right that some studies and project management costs remain a ‘tax nothing’? For innovative projects in particular, this type of expenditure is likely to be more commonplace.

Recently, I saw a BBC news story about super-sized heat pumps in Gateshead and London. My immediate reaction was: “This is clever, but will they face a battle to agree the tax treatment?”

About the author

Lindsey Wicks, Technical Editor, Tax Faculty