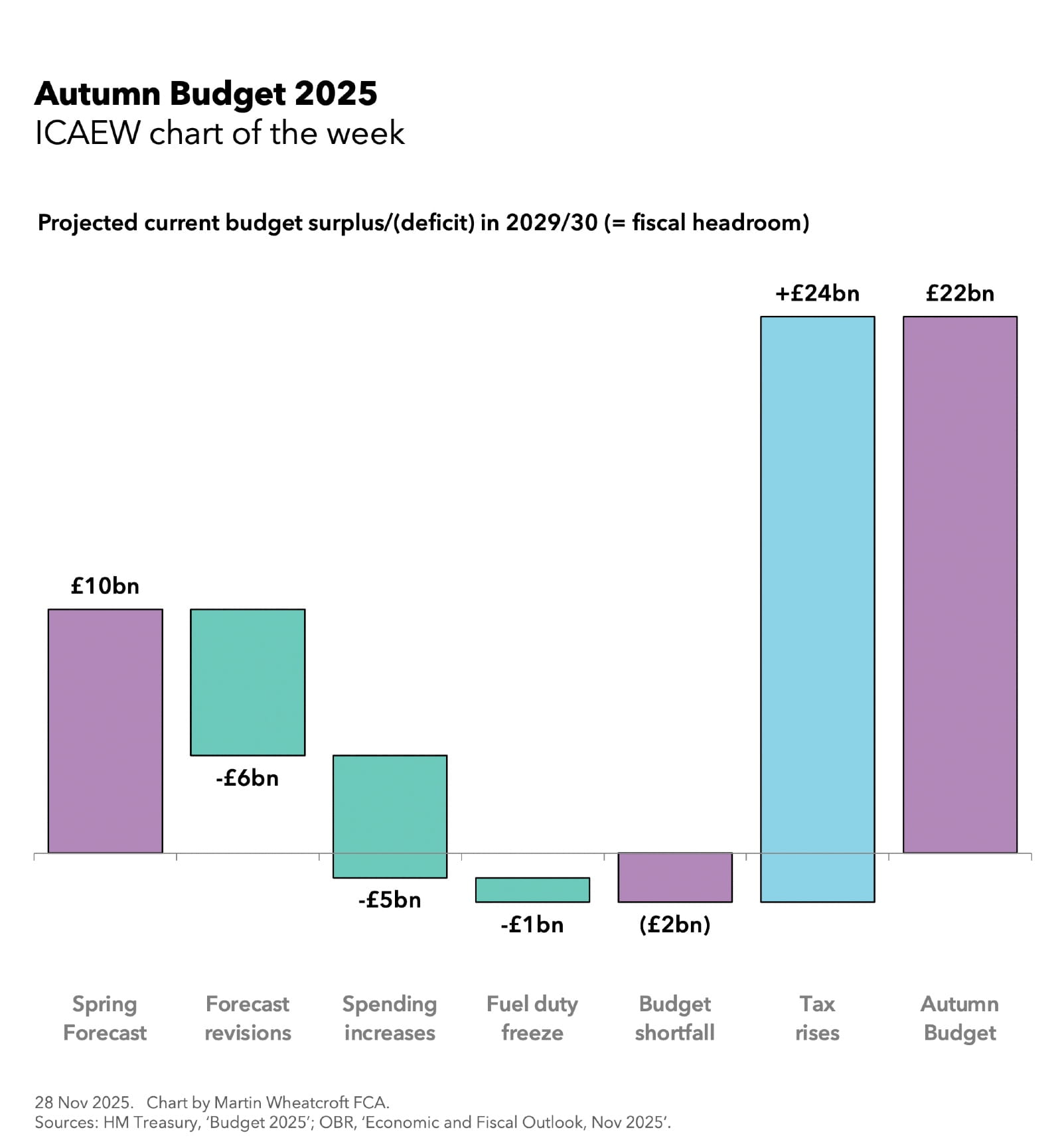

Our chart this week shows how the projected current budget surplus of £10bn in 2029/30 was reduced by £6bn of Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecast revisions, by £5bn of spending increases announced in the Autumn Budget, and by £1bn from the freezing of fuel duties for yet another year.

Together these reduced the Chancellor’s headroom against her primary fiscal rule (to be in a current budget surplus by the fourth year of the fiscal forecast) from £10bn to minus £2bn – in effect breaching her fiscal rule before taking account of tax rises.

The Chancellor has then restored – and increased – her fiscal headroom to £22bn through a long list of tax rises that are anticipated to generate £24bn more in receipts in 2029/30.

Forecast revisions

The rumoured forecast downgrade from the OBR of £6bn in 2029/30 turned out to be much less significant than expected.

The OBR cut its receipts forecast for 2029/30 by £16bn a year because of weaker assumed productivity growth. But this was more than offset by a £30bn increase from higher nominal wages and prices, driven by both inflation and real wage growth, to add £14bn to receipts in that year – an increase not a decrease to the receipts side of the forecast.

This was offset by £20bn in higher current spending, of which £6bn was from higher uprating of welfare benefits and growth in claimants and caseloads, £6bn from government policy reversals on the winter fuel allowance and disability benefits, £4bn in higher debt interest, £2bn in higher local government spending, and £2bn in other changes.

The resulting deterioration of £6bn in the projected current budget surplus for 2029/30 was £14bn smaller than the £22bn deterioration anticipated by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) in its pre-Budget forecast (as used in our chart of the week on the Autumn Budget hole). The principal driver was £22bn in incremental receipts from higher inflation and higher real wage growth less £6bn in higher spending for similar reasons.

Because departmental budgets for 2026/27, 2027/28 and 2028/29 set out in the Spending Review earlier this year have not been increased for this higher level of inflation, the risk is that future Budgets will need to top up the amounts allocated to departments to deal with cost pressures that are likely to arise.

Spending increases

Current spending is projected to increase by £5bn in 2029/30, comprising £3bn to cover the annual cost of abolishing the two-child benefit cap, £1bn in higher debt interest, and £1bn in net other changes in non-interest current spending.

The OBR also announced that it had reduced its underspend assumption for departmental budgets during the latest spending review period (2026/27 to 2028/29 for current spending) by an average of £4bn a year to reflect the increased pressures on budgets from higher inflation. There was no similar adjustment to 2029/30 current spending as it is not covered by the spending review, but there is a risk that a similar adjustment may be needed by the time of the 2027 spending review.

Fuel duty freeze

Freezing fuel duties has become a consistent feature of Budgets since 2011, with the effect of reducing annual tax receipts in real terms by just under £1bn a year.

Given the current Chancellor has chosen to continue this practice in two successive Budgets, it is disappointing that fiscal forecasts have not reflected the anticipated £3bn additional reduction in tax receipts in 2029/30 if fuel duty is frozen again in the next three Budgets.

Tax rises

The Chancellor announced a total of £27bn in tax rises in the Budget (£26bn if the fuel duty freeze effective tax cut is netted off), but this is expected to generate £24bn in incremental tax receipts once behavioural responses and other indirect economic effects are adjusted for.

These tax rises are expected to generate the following amounts per year by 2029/30:

- £8bn from extending the freezing of personal allowances (more ‘fiscal drag’).

- £5bn from restricting the use of salary-sacrifice schemes to make pension contributions.

- £2bn from increased income tax rates on property, savings and dividends.

- £1.5bn from changes to writing-down allowances.

- Just under £1.5bn from a mileage-based charge on electric cars.

- Just over £1bn from gambling duty reform.

- Just under £1bn from capital gains tax on employee ownership trusts.

- Just under £0.5bn from a high value council tax surcharge.

- Around £4.5bn from other tax measures.

- £2bn from improved tax compliance and collection.

Higher headroom

The Chancellor chose to increase headroom against her principal (current budget) fiscal rule from £10bn last year to £22bn and to increase headroom in her secondary (debt) fiscal rule from £15bn to £24bn.

These are both positive in that they provide a much bigger cushion against potential forecast downgrades in the spring or autumn next year, reducing the risk of another round of significant tax rises in the Chancellor’s third Budget in 2026. It also helps that she is likely to gain around £15bn of extra headroom as the main fiscal rule moves to being tested in the third year of the forecast, which comes with a margin of permitted current budget deficit up to a maximum of GDP.

However, significant downside risks remain, so this outcome is far from assured. The Chancellor still faces the challenge of reviving a weak economy and delivering substantial efficiency savings if she is to keep public spending under control in the absence of more fundamental reform. That task is made harder by the risk of bailouts for local authorities and universities, and by continued pressure on the welfare budget.

ICAEW on the Budget