Now that the dust has settled on November’s Budget, we have published a 20-page in-depth Fiscal Insight report on the government’s most recent fiscal event and what it means for public finances.

One of the key conclusions of the report is that this Budget was ‘all about the headroom’, with the Chancellor’s tax rises almost entirely devoted to improving the buffer against potential adverse economic developments.

Although the government does not have an explicit long-term fiscal strategy, it does have medium-term strategic objectives to end the use of borrowing to fund current spending and to stop public debt from rising faster than the size of the economy.

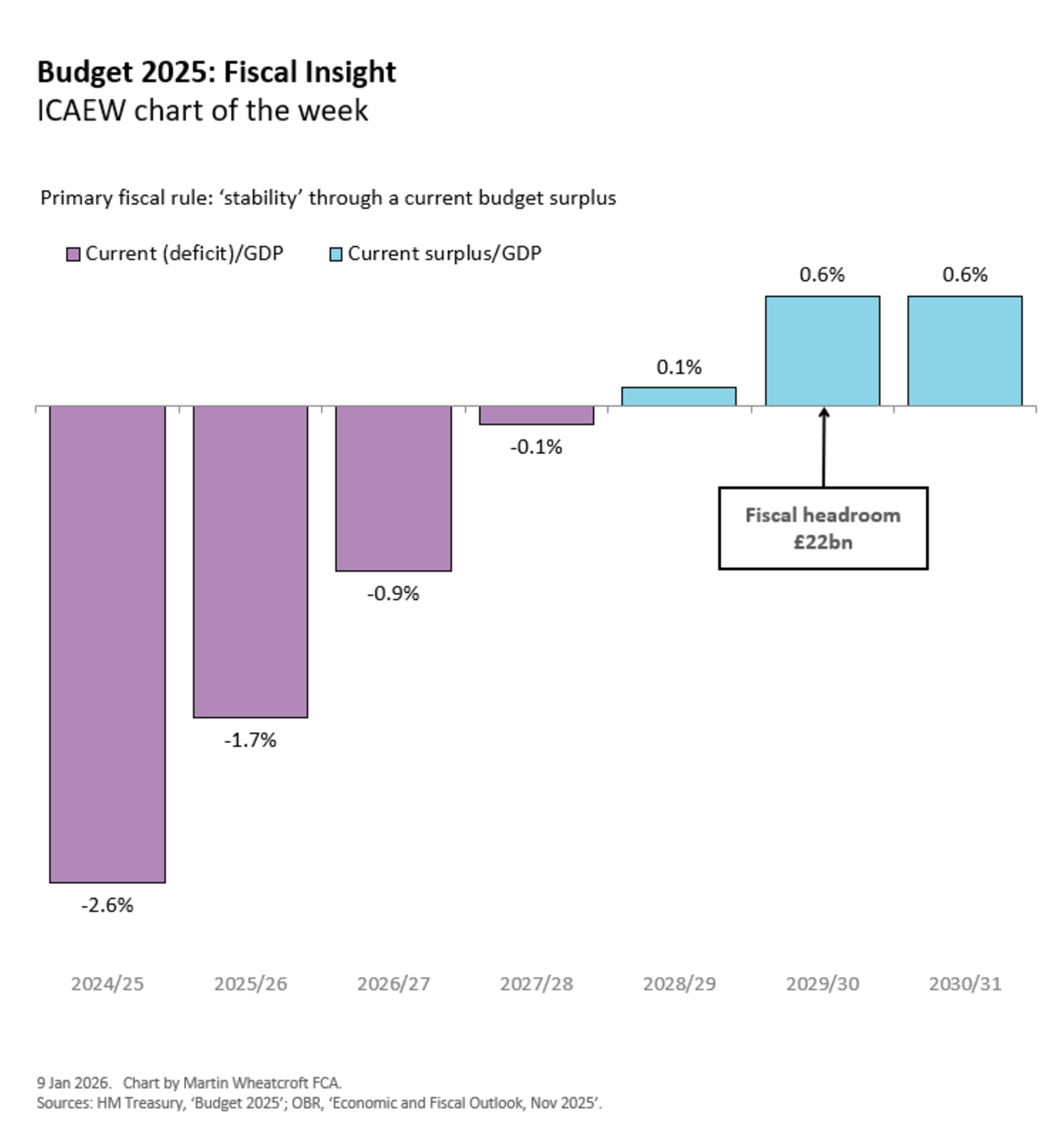

These aims are embodied in fiscal targets that are intended to provide confidence to debt markets about the government’s commitment to keeping public finances under control. The Chancellor’s primary ‘stability’ fiscal rule targets a current budget surplus by 2029/30 – the fourth year of the fiscal forecast period – as illustrated by Figure 3.

In theory, this rule prevents the government borrowing to fund current spending and reduces the incentive inherent in previous fiscal rules to attempt to ‘balance the books’ by cutting investment.

Fiscal Insight report

Take a look at the Budget 2025 Fiscal Insight report.

Budget 2026 later this year will reduce the fiscal target to three years. This is a major improvement as it aligns with the three-year spending review period and hence should significantly reduce the scope for ‘playing with spreadsheets’ to meet fiscal targets.

The tightening in this fiscal rule is accompanied by a slight relaxation in the target: instead of aiming for a current budget surplus, the rule now allows a maximum current budget deficit of up to 0.5% of GDP. This should provide the Chancellor with around £17bn in additional headroom on top of the existing £22bn she has this year, before taking account of changes in the fiscal forecasts or policy decisions in 2026.

This is likely to mean that her secondary fiscal rule – requiring projected debt to start falling by 2029/30 – will become more important in determining whether she will meet her fiscal commitments next year.

It is generally accepted that the Chancellor left herself with too small a level of headroom against her fiscal rules in the Autumn Budget 2024. This left the government vulnerable to relatively small swings in economic circumstances and also constrained the government’s ability to spend more on defence or other emerging priorities.

The need to respond to a deterioration in the fiscal forecasts saw the Chancellor cut planned welfare spending in the Spring Statement, followed by hugely damaging speculation about potential tax rises in the run up to Budget 2025 following the overturning of those cuts by Labour MPs.

Although the level of headroom is still not that high by historical standards, the additional £17bn of headroom she is scheduled to benefit from in next year’s Budget should provide her with more resilience to weather further deteriorations in the economy if needed.

ICAEW on the Budget