Business performance measurement sounds simple. But for it to have an impact there must be an underlying story of where the organisation is going – a tale understood and endorsed by everyone involved. David Baines explains finance’s crucial role in writing that story – and choosing the measures that underpin it.

There has to be a story behind the measures for this to work. This story describes how your organisation is going to achieve its objectives – and the key things you have to accomplish in order to do so. The story has to be easy to follow and plausible. If it’s done right, the performance measures will follow naturally.

But does your organisation have such a story and can you put your hand on the document that tells it? Is it easy for everyone to understand, can they tell the story unprompted, do they believe it?

Unless you can answer “yes” to these questions… why should people strive to achieve the measures by which you judge them? Without their active agreement you have to resort to hoping that they do what you tell them.

Carrots, sticks and stories

My firm has come across many FDs, and

their departments, who are desperately

seeking the magic measures that will make

the massive difference to performance.

But whatever carrots or sticks finance

uses, the rest of the organisation seems

impervious to its engagement. The nub of

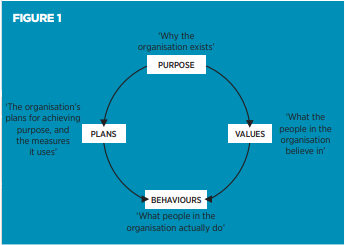

the problem (see figure 1, overleaf) is that

people’s behaviour is driven by two forces:

- What the organisation tells them to do – the “plans” route on the left.

- What they think is important and what they want to do – the “values” route on the right.

If people don’t understand the plans – or don’t agree with them, or don’t think the measures reflect the plans – the two routes conflict. The bad news is that the “values” route usually wins hands down. If your plans are so far removed from what other people in the organisation think should be done, you have a problem. It’s likely people simply do not know what the plans are, or the reasoning behind them, or think that the measures are wrong or unfair. This is where the story comes in.

Finance's wider remit

So what is the role of finance here? A

narrow view is that finance reports the

financial numbers of costs and revenues

by whatever categories the chart of accounts

and the ledger codes dictate. In these

circumstances management reporting

might only consist of budget variances by

budget line, supported by explanations that

give varying levels of insight.

Anyone who has endured this approach

knows how futile and unrewarding it can be.

A typical bad example is a narrative that

amounts to something like: “The negative

variances occur because the wishful

thinking about sales and cost efficiencies

we used in the budget hasn’t been realised,

but fortunately these are offset by positive

variances due to our being unable to

realise our plans and spend as quickly

as we had hoped.”

Finance should have a much wider remit

in the field of performance measurement:

no one else offers a logical case for taking

the role. Under this remit, you are

responsible for:

- writing the story describing how your organisation is going to achieve its objectives;

- creating a model that projects the financial results from pursuing the story successfully;

- telling and selling this story so that everyone understands and agrees with it – or modifying it until they do;

- identifying the measures, financial and non-financial, that underpin the story;

- presenting these measures along with explanations of why they differ from forecast; the likely outcome if nothing is done to change matters; the options that exist for changing course; what the likely outcome of pursuing these options would be; and

- designing and owning the process by which measures are decided, measured, presented and acted upon.

If your plans are so far removed from what other people in the organisation think should be done, you have a problem

Lighten the workload

For instance, the responses of 123 large UK organisations in a 2004 survey revealed they take on average 3.7 months to create their budgets. Half the respondents said budget figures become outdated and ignored before year end: the average time into the year when the budget figures become outdated is 4.25 months (just 16 working days longer than it takes to produce the budget in the first place). You can’t deny there is a great deal of wasted finance effort reporting and explaining monthly variances in these circumstances. Similarly persuasive arguments can be advanced about many of the reports that are produced.

I am not suggesting these activities don’t add any value, merely that, given a finite resource, one has to prioritise. The benefits of an effective performance measurement system that helps you achieve corporate objectives outweigh the benefits of detailed ledger line variance analysis done by rote.

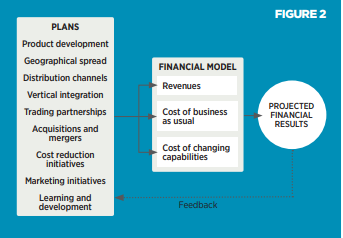

Another bullet point in the list above, setting out finance’s role in performance measurement, relates to creating a financial model of the organisation. Such a model (illustrated diagrammatically by figure 2) is important because it can provide the acid test for the plausibility of the story. If you can use such a model to win over the sceptics, you are home and dry.

The story

The role of finance in performance

measurement outlined above is sketchy. The remainder of this article will endeavour to

put some meat on the bones. Let’s start with

the story sitting behind the measures. One

approach – and it is only one – is to use the

balanced scorecard, which is popular but

often misapplied.

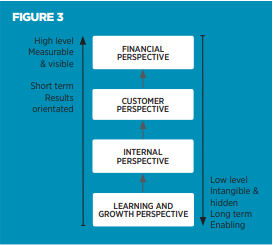

The balanced scorecard proposes

four perspectives: financial; customer;

internal; learning and growth. For each

perspective a set of appropriate measures

is selected. What isn’t always made clear

is that these perspectives are

interdependent. They build upon one

another in a specific sequence (see figure 3).

The underlying rationale is that to

achieve your financial measures, such

as greater asset utilisation or increased

revenues, you need to set and achieve

a ‘customer value proposition’ – your

proposal to customers of the value you will

deliver to them.

In order to do this, you need to get

your internal delivery mechanisms – or

business processes – working effectively,

and to do that you need to grow appropriate

capabilities: of your people; your IT; and

your organisational structures and ways

of working.

You can work on achieving your

measures in each perspective at the same

time, even though the measures in the

lower perspectives support those higher up.

The important point is that the chosen

measures must be related to one another in

the linked sequence: your learning and

growth measures must be ones that support

the attainment of your internal measures,

and so on in a chain up the structure.

While the name “balanced scorecard”

implies that what is needed is a balance of

the four perspectives, it doesn’t imply as

clearly that the measures need to link to one

another, which is key. Without the links

between specific measures in the different

perspectives, you run the risk of ending

up with four boxes full of any old important-sounding measures.

You will probably find that piecing

together the key elements of each

perspective into a coherent, sound structure

that delivers the objectives of the

organisation is not easy. But the effort is

worthwhile because out of it will come the

story and the associated measures.

To achieve your financial measures you need to set and achieve a ‘customer value proposition’

Key measures

If the balanced scorecard is out of favour in your organisation, and you desperately want to get away from reporting a mass of ledger line variances, I offer the following approach to generating a basic set of performance measures.

Choose measures that answer the following set of questions:

- Strategic:

Is each product/market segment behaving as we expected (competitor activity; market size; prices; market share)? - Plans for change:

Is implementation going according to planned timescale and cost?

Are the effects of implementation as forecast (eg better customer service; growth in customers; lower unit costs)? - Business-as-usual:

How are key measures of customer service moving, particularly in relation to competitors?

How are unit costs moving?

How are revenues moving compared to forecast?

Hierarchy of measures

The purpose of performance measures isn’t only to measure performance but also to explain why actual performance differs from forecast or target. In providing this explanation, performance measures can answer one of two questions:

- Have we done what we planned to do?

- Has our plan achieved what we forecast?

There is an obvious distinction between these two questions – one relates to an outcome that fails because we haven’t done what we said we would; the other to one that fails because our judgement about the results of our actions was wrong. It is important to have both types of measure in your mix.

However, while a mixture of both types of measure will usually give a satisfactory explanation when you haven’t done what you said you would, it may fail to do so when you have done what you planned and yet the result isn’t as predicted. In the latter case there is a danger that people abandon the whole performance measurement system as being unhelpful.

If this happens, resist. There will always be a reason for outcome differing from forecast and it is essential that you nail down this reason in order to do something about it. Don’t abandon your measures because they initially send confused signals – persevere with them and dig for the answers, which will probably lie in one or more of the following areas:

- insufficient time for your efforts to bear fruit;

- a missing element to your plans;

- a flawed judgement about how the market would react to your proposition; or

- an unnoticed competitor move.

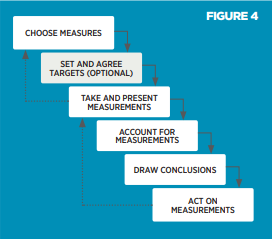

Performance measurement is a process

Performance measurement isn’t simply the task of making measurements and publishing them. It is a cyclic process that starts with deciding appropriate measures, moves on to deciding what actions to take as a result of the measurements obtained, and ends with implementing these actions. Different players do different things at various points in the process. Map your process, and ask yourself whether each stage is fit for purpose.

To ensure you have good measures, and to weed out unnecessary ones, ask questions about each one, for example:

- What is the purpose of the measure, and does the purpose justify the effort?

- Should there be a target, and if so what is the planned achievement date?

- Who is accountable – named person – for the measurements?

- Who will assess performance?

These might sound obvious questions, but it is surprising how often performance measurement systems degrade into a data collection and presentation task for finance, the product of which no one heeds (see illustration in figure 4).

In a nutshell

The difficult bit, as always, is getting the rest of the organisation to follow your line. To do so, provide a story that describes and explains what people must accomplish to meet the overall goals, and the measures that will track progress. Create a model that demonstrates how the financial results follow from making the story come true. Lead the way!

About the author

David Baines is a director of Freeman Baines Consulting. He has written several management books, including a performance measurement handbook.

Download PDF article

- Tales of the expected, Finance & Management Magazine, Issue 204, November 2012

Further reading

The ICAEW Library & Information Service provides full text access to leading business, finance and management journals and a selection of key business and reference eBooks.

Further reading on performance measurement is available through the resources below.

You are permitted to access, download, copy, or print out content from eBooks for your own research or study only, subject to the terms of use set by our suppliers and any restrictions imposed by individual publishers. Please see individual supplier pages for full terms of use.

More support on business

Read our articles, eBooks, reports and guides on Financial management

Financial management hubFinancial management eBooksCan't find what you're looking for?

The ICAEW Library can give you the right information from trustworthy, professional sources that aren't freely available online. Contact us for expert help with your enquiries and research.

-

Update History

- 09 Nov 2012 (12: 00 AM GMT)

- First published

- 14 Nov 2022 (12: 00 AM GMT)

- Page updated with Further reading section, adding related resources on performance measurement. These provide fresh insights, case studies and perspectives on this topic. Please note that the original article from 2012 has not undergone any review or updates.