The UK’s national tax burden is on the up and people’s expectations of fiscal policy are shifting. We tour the globe to discover how the UK’s taxes compare internationally.

Do high taxes and high transparency go hand in hand?

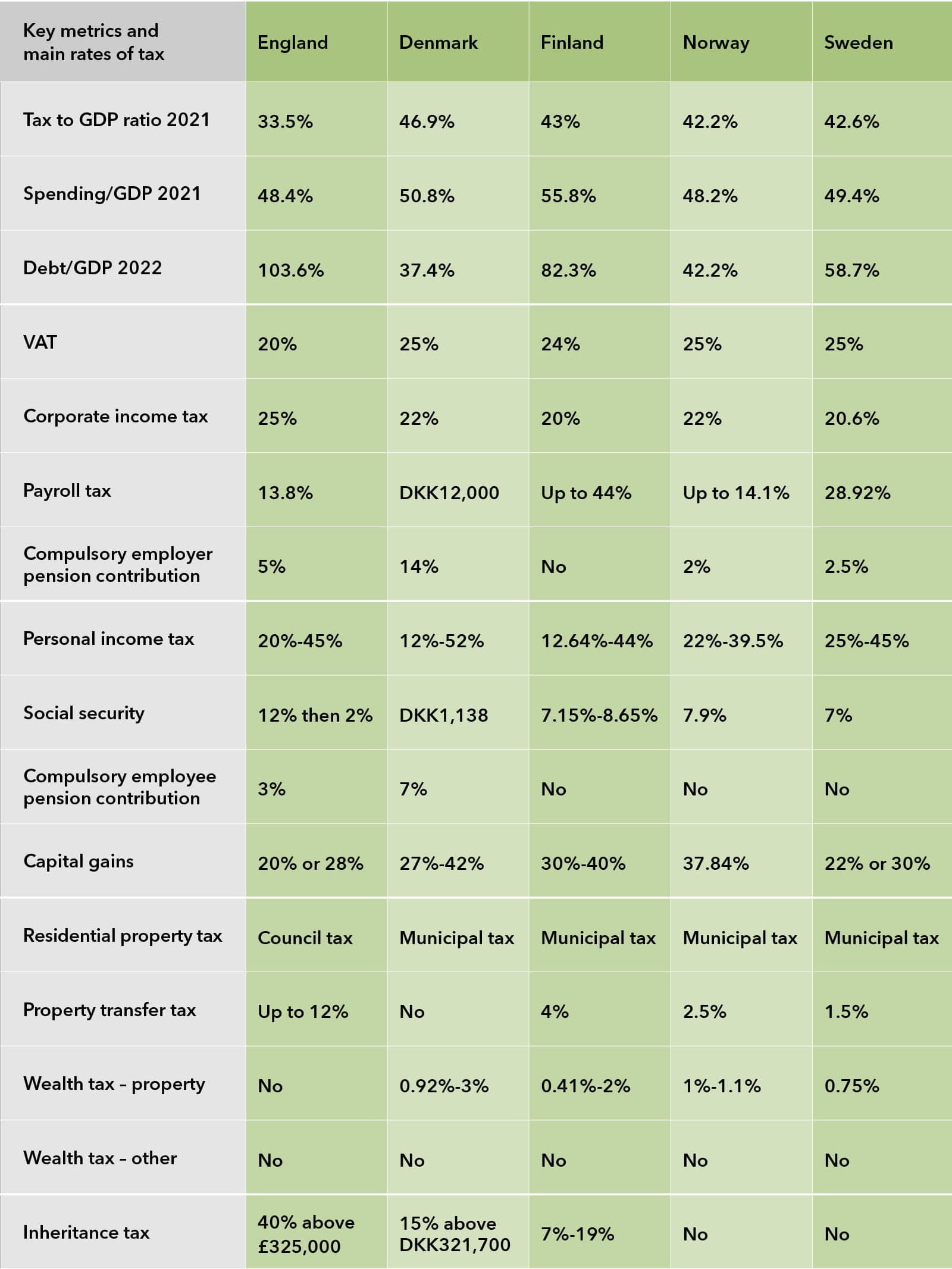

Taxation as a percentage of GDP is steadily ticking upwards in the UK and is forecast to reach 37.7% in 2027-28, its highest level since World War Two. However, it will remain well below levels found in Nordic countries, which ranged from 42.2% in Norway to 46.9% in Denmark according to OECD figures for 2021. By way of comparison, taxation as a percentage of GDP was 33.5% in the UK in 2021.

The Nordics are well known for high income taxes, with the highest rate of tax topping 50% in both Denmark. In addition, consumption taxes are considered to be a key reason why the tax take is proportionally higher than many other OECD countries: VAT is 24% in Finland and 25% in the other three Nordic markets. Corporate tax rates, however, are in line with those in the UK and range from 20 to 22%. It should also be noted that Norway and Sweden hold the distinction of not levying inheritance tax (IHT).

While Nordic countries may be among the first to spring to mind when thinking of high taxes, this is coupled with a reputation for excellent public services and high standards of living. Notably, the countries also have governments in stronger financial positions than the UK, with government debt as a proportion of GDP ranging from 37.4% in Denmark to 82.3% in Finland.

The Nordics are also known for a high degree of tax transparency. With the exception of Denmark, the countries openly publish tax records. Norway has published tax records since 1863, while Finland shares the names of the country’s 10,000 biggest earners each year. Proponents point to how individuals can use the information to better negotiate their salaries, while also promoting equality more generally by encouraging flatter pay structures.

What forms can a wealth tax take?

In the UK, the Wealth Tax Commission has led calls for a wealth tax to be introduced, aiming to reduce inequality and raise additional funds for government spending. But questions remain over the exact method of extracting the tax and the thresholds, taxable assets and rates that will apply.

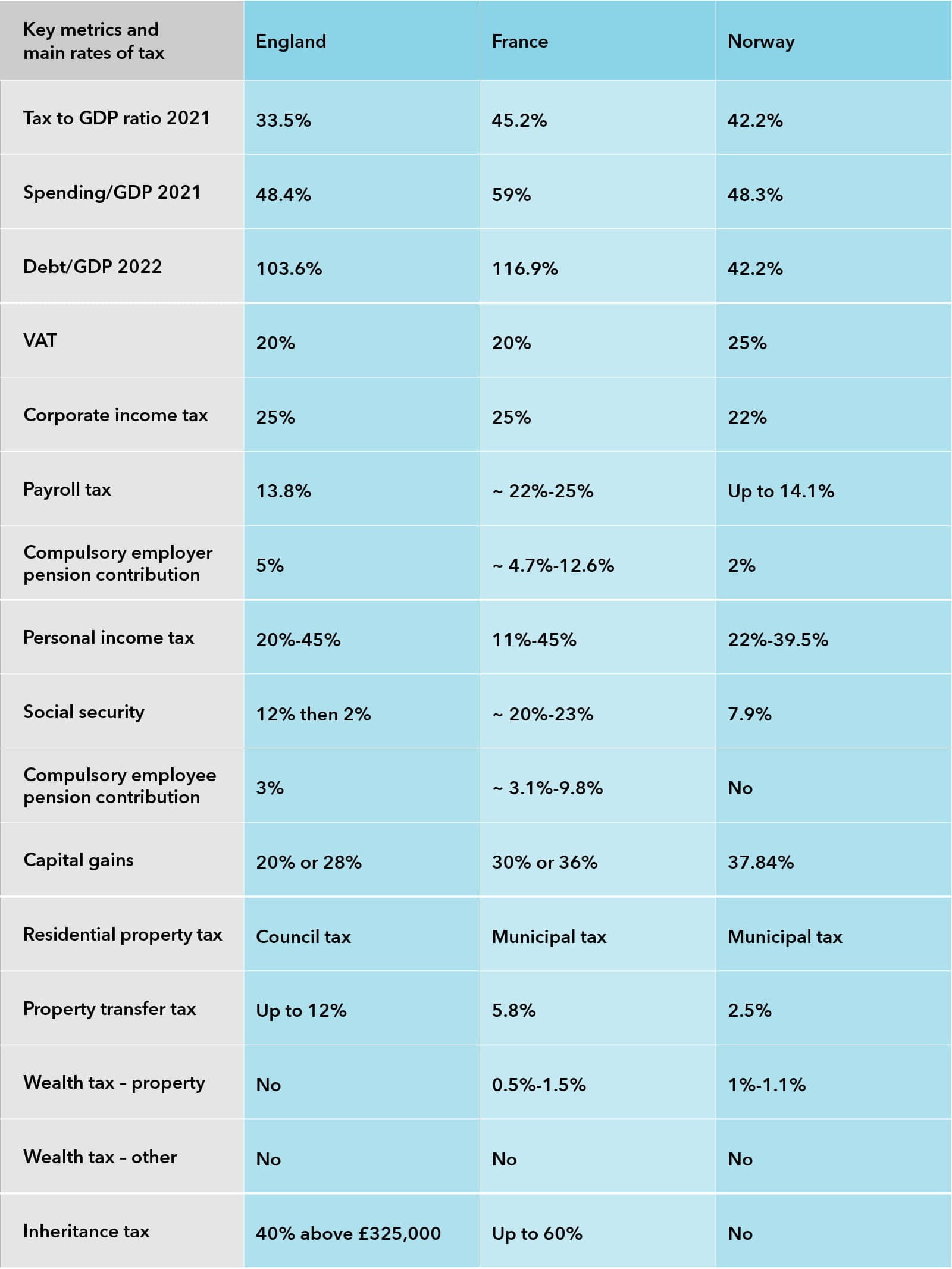

Many countries, including Germany and the Netherlands, repealed wealth taxes during the 1990s and 2000s. However, France and Norway are two examples of countries where wealth taxes are well established, and have had recent tweaks aimed at modernisation.

The French wealth tax is known as ‘impôt sur la fortune immobilière’ (IFI). It is payable by those with more than €1.3m in worldwide property assets, though is charged on any property assets over and above €800,000. Those living in France also receive a 30% allowance against their primary residence. Levied at a household level, the current rates are 0.5-1.5% charged annually. IFI was introduced in 2018 and replaced the much-criticised wealth solidarity tax, known as ‘impôt de solidarité sur la fortune’ (ISF), which was wider in scope and included savings, investments holdings, cars and jewellery.

Norway’s wealth tax applies to those individuals whose net wealth (including property) exceeds NOK1.7m (approximately £127,000). The total value of any assets above this amount is taxed at 1%, with 0.3% going to central government and 0.7% going to the local municipality. For those individuals whose net wealth exceeds NOK20m (approximately £1.4m), an extra 0.1% is levied.

Questions remain over the effectiveness of these taxes in maximising the overall tax take and whether they have encouraged the wealthiest individuals to make their main residence elsewhere. French economist Eric Pichet estimated that the original ISF cost France twice as much money as it generated. Similarly, in Norway, the increase of the wealth tax to 1.1% for the wealthiest individuals has led to reports of individuals leaving the country.

Addressing inheritance tax’s unpopularity: scrap or reform?

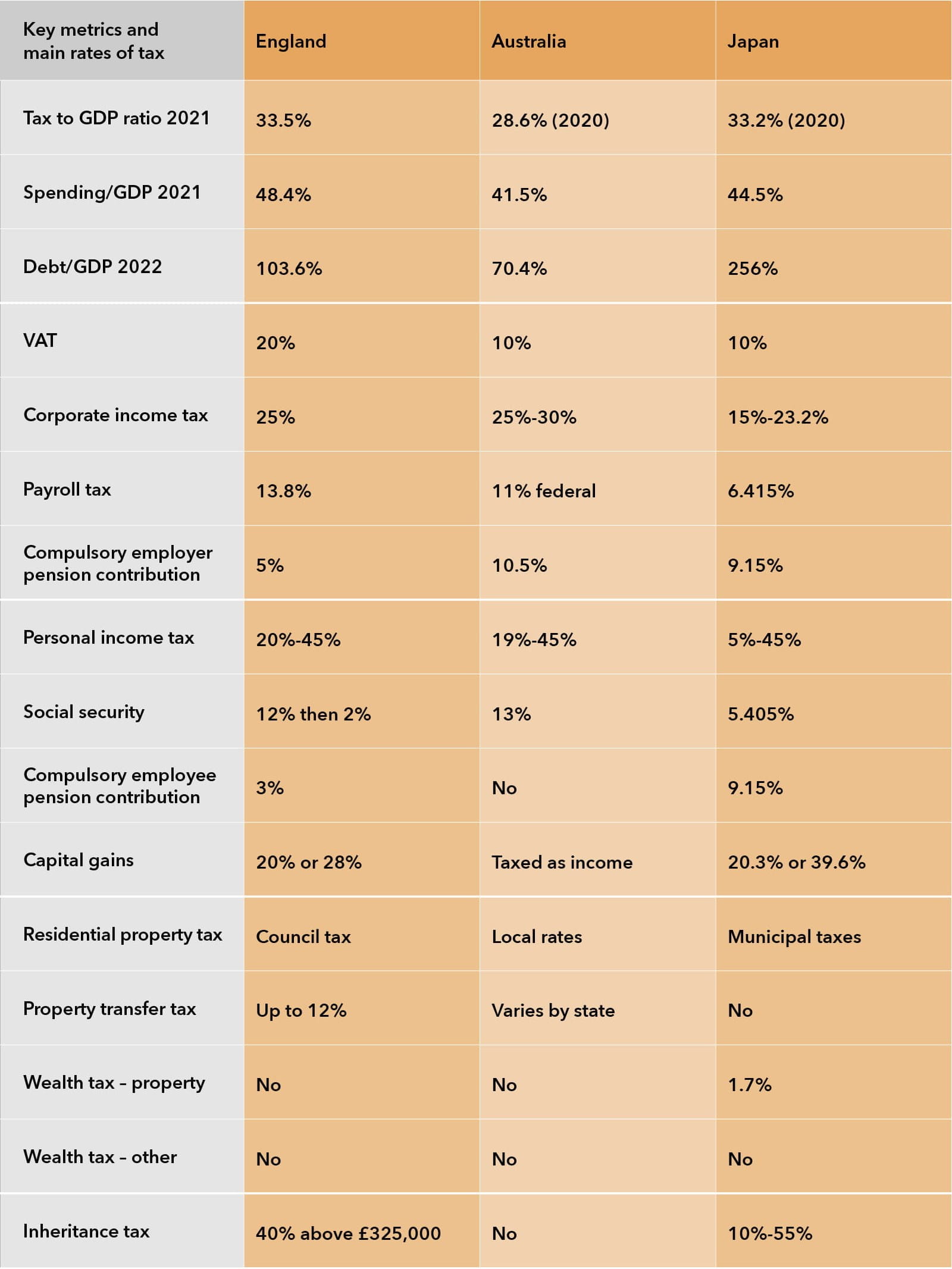

Inheritance tax (IHT) is the UK’s most unpopular tax: YouGov data from April 2023 shows that 50% of people consider it to be unfair or very unfair. With thresholds frozen for a number of years and a growing number of estates falling liable to pay, pressure for reform is gathering momentum. IHT rates vary significantly across the globe – from zero in Australia to Japan as the highest – and there are a number of models the UK may draw inspiration from.

Australia was one of the first advanced economies to abolish inheritance tax in 1979, with periodic reviews continuing to decide against its reinstatement. However, inheritors may be liable for capital gains tax if they dispose of an inherited asset. As with the UK, there is no forced heirship in Australia, with individuals able to choose who they leave their estate to. Other examples of markets that do not levy inheritance tax include Canada, Mexico, and Singapore.

At the other end of the spectrum lies Japan, where inheritance tax rates start at 10% for any inheritance under JPY10m (£770,000) and reach as much as 55% from JPY600m (£42m). Death duties are payable by the inheritors, unlike the UK where it is the estate that pays the bill. According to Japanese civil code, a spouse is entitled to 50% of any assets, with the remainder divided equally among any children. As a result, estate planning is a significant element of financial planning and tax advice in the country.

Does simplification unlock competitiveness?

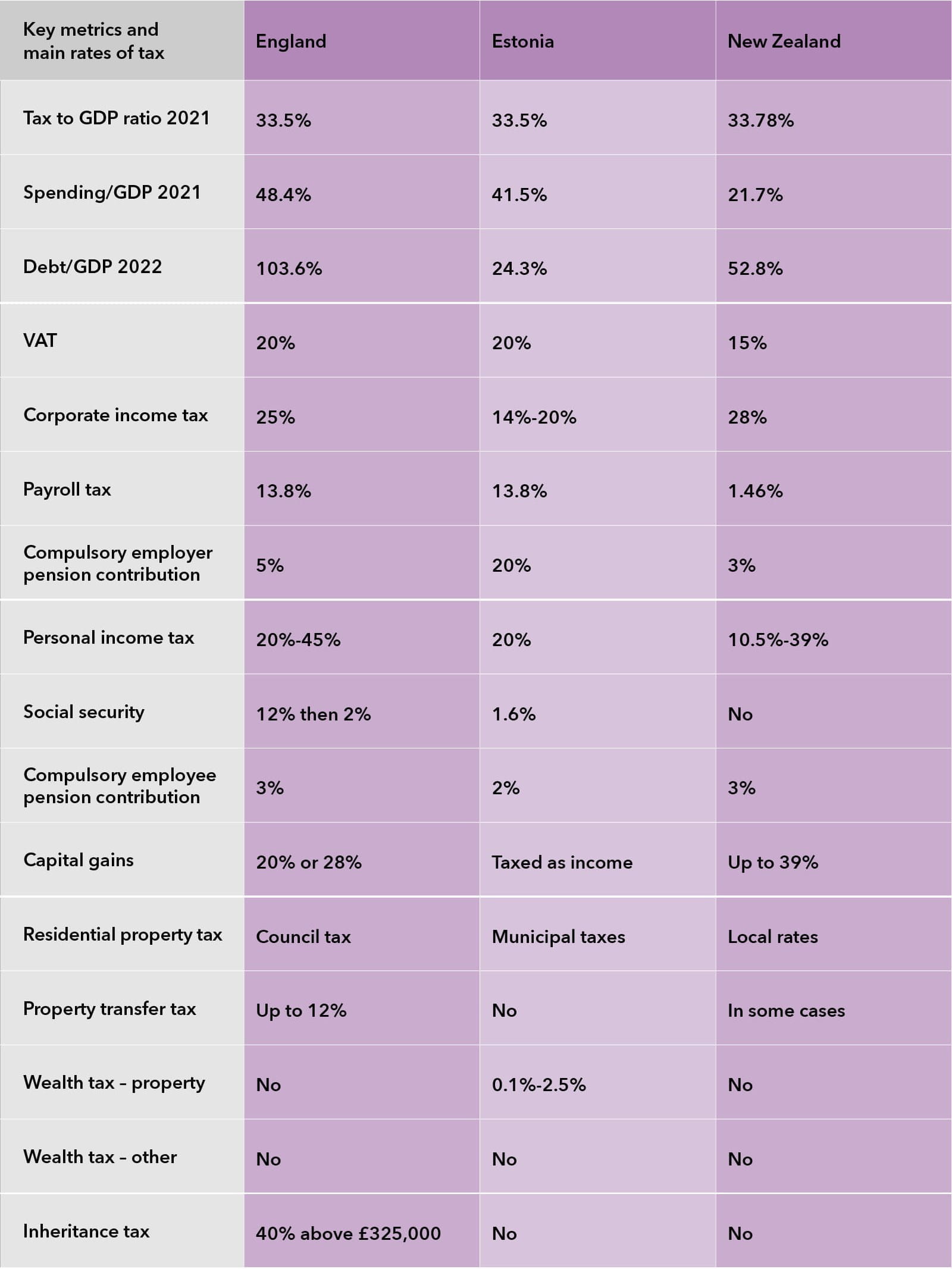

The UK’s tax regime is considered relatively complex by international standards. Two leading examples of tax simplification are Estonia and New Zealand, which US non-profit The Tax Foundation ranks as leading markets in its International Tax Competitiveness Index. The UK, for comparison, comes 26th.

Estonia has topped the rankings since 2014. One stand-out feature is its 20% rate of corporation tax, which is levied on distributed profits only. From an individual perspective, there is a flat rate of personal income tax of 20% (which is set to rise to 22%), capital gains are taxed as ordinary income and there is no IHT. In addition, Estonia is noted for a strong e-filing tax system, which is considered to have improved compliance by individuals and corporates alike.

New Zealand places third (after Latvia) on the Index. The country is noted for a simple consumption tax regime, with a rate of 15% applying to almost all goods and services. There is no inheritance tax and property transfer taxes are only paid when the sale is to an individual resident outside of the country. From a corporation tax perspective, the rate of 28% is above average, but this is balanced by New Zealand’s well-known policy of allowing corporate losses to be carried forward indefinitely.

Tax to GDP: Tax revenue – OECD Data

Debt to GDP: General government debt – OECD Data

Government spending to GDP:

General government spending – OECD Data

New Zealand Government spending, percent of GDP – data, chart | TheGlobalEconomy.com

Tax information: Worldwide Tax Summaries