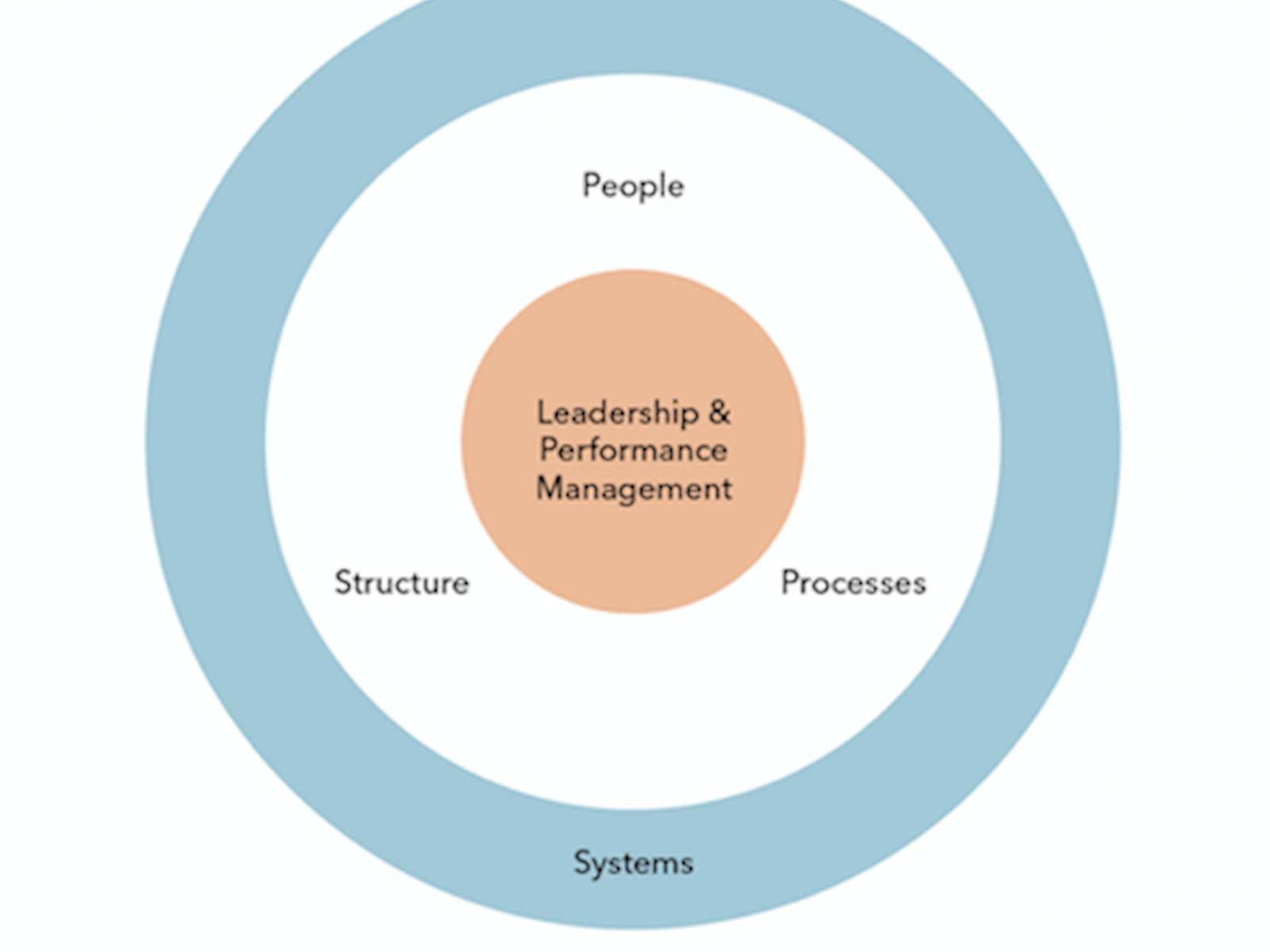

In the introduction to this series, I introduced what I call the five pillars of a successful finance transformation strategy. These are as follows:

- Appropriate leadership and performance management

- The right structure

- The right processes

- The right people

- Supported by the right systems

Over the course of the five articles, I’ll focus on each pillar individually, with the aim of providing a toolkit to help finance leaders manage a successful transformation strategy. In the last article we covered the pivotal topic of leadership and performance management, and this time we look at the role of structure.

Structure: balance is key

Normally, hearts leap when senior leadership calls an all-hands meeting to announce that they want to transform the organisation’s design. ‘At last’ staff think, ‘they’re finally taking it seriously’. However, more often than not within five minutes those hearts sink back down again, because it’s obvious that they’re only thinking about how to change the organisation’s structure. As I’ve explained on a number of projects over the years, if your transformation strategy just focuses on this pillar this will almost certainly lead to failure.

I’ve talked about why it’s not all about structure, but it is still a key consideration when thinking about a potential transformation. It’s important that an organisation has the appropriate structure in place, with standardised role profiles.

However, a lot of people look at the structure but forget about the people, process and system parts. You have to put everything together - these should be in balance with the four other pillars in the diagram above.

Creating the right organisational structure takes a lot of design work. I’ve seen lots of people think they can solve the world by altering an organogram on a piece of paper - there was a lot of this in the ‘80s and ‘90s - and more often than not it doesn’t work.

Are the benefits of the transformation defined?

In the previous article, I mentioned three simple questions finance leaders should ask before embarking on a transformation project. For this pillar, one question stands out as important: ‘are the benefits of the transformation defined?’

It’s crucial to analyse the benefits before embarking on the project and continue to go back to these objectives throughout it. Is it about cost saving? Increasing internal controls? Understand what’s motivating the project and you’ll make better decisions (and get better outcomes).

In a typical transformation project, examples of areas on which senior management might want to focus include delayering the organisation (from, say, five to three) or increasing spans of control (the number of individuals reporting into a single line manager).

Sometimes in such projects, the benefits you ultimately gain might be different to the ones you were looking for at the start.

Techniques such as ‘five whys’ analysis - an engineering approach used in management to explore the underlying issues of a particular problem by asking the same question repeatedly - are a good starting point to unravel the benefits you might be looking for. You may start out only interested in revenue growth, and after drilling down find that actually you want to focus on top-line growth, not just cost.

How to tackle structure

Structure lays out the different building blocks (roles) in an organisation. People double click on one of those building blocks and it shows what’s required for a person in one of those roles to be successful.

To get things started, here are three questions you might want to ask when looking at your structure.

a) Is this defined within the organisation?

Does an up-to-date version of your organisational structure exist? Does it cover the following?

- Roles: there should be a limited number of job titles - colleagues doing similar work should have the same role definition.

- Reporting lines: depending on your organisation, there may be a split between solid line and dotted line, delivery and functional management, but the important thing is it’s clearly defined.

- Responsibilities: the high-level definition is who is responsible for what gets delivered by this role, and which processes it needs to be adhered to. Therefore, the link to the process pillar is critical. In this series, the people pillar covers the detail needed for a standard role definition required for an efficient organisational design.

b) Is this aligned with the other pillars?

We have covered how the structure pillar ties in with benefits and leadership above, and also highlighted the link to people and processes.

Another pillar not to forget is systems and tools. Within the responsibilities it should be clear which leadership roles own the integrity and performance of which systems. For example, does the financial reporting manager own the general ledger? Does the commercial finance manager or the sales manager own the sales pipeline system? What gets measured gets done - it’s almost a maxim for the whole transformation process.

c) Is this pillar managed effectively?

In this section, I’d like to emphasise the importance of linking the structure pillar to leadership and metrics. From our GAME plan approach, the G highlights the GAP analysis. The ‘as-is’ organisational structure for what exists today, Gap analysis then compare this with the ‘to-be’ org structure (sometimes referred to as the ‘role model organisation’), which is our longer-term vision in a perfect world.

To help with this, here’s an updated version of the GAP analysis template we featured in the previous article, along with an updated version of the Action Plan template.

The difficult bit starts here. We know where we are and what we want, but what is realistic to achieve with the people, money, timescale and, most importantly, the appetite of leadership to drive the change towards the desired future state.

Let’s take two extreme approaches. One is we change everything overnight - it achieves a gold star for the organisational structure but for other pillars could cause serious issues. It might break processes, as people don’t know what they’re doing. It might break people as they don’t understand their new roles. It might break systems, as they’re not geared up for a new way of working. This adds up to a potential disaster for leadership.

The other way is by attrition - a slow, cautious, approach to change. However, by the time you achieve it, the role model may well be out of date. The reality is a difficult space in between - the hybrid.

This is all before you add in the politics and unsaid issues that are generally just below the surface when changing an organisational structure. Within leadership there will be winners and losers. Some try to do the right thing for the organisation, while others will play every type of political game to increase their own power.

To end with a personal reflection, one thing I always try to emphasise in any transformation project I lead or am involved with is that however fast you think you’re going, it’s always good to go harder and faster.

There’s so much natural resistance within organisations to change - there’s a reason why attaining a “clear mandate from leadership” is so vital in getting any change strategy off the ground. The majority of the issues I’ve outlined above can be resolved if you’ve got a clear mandate and visible support from leadership. You can then move to effective execution by managing with project discipline.

In the next article in this series, we’ll look at how to make sure your organisation has the appropriate process architecture in place to enable teams to deliver.

Further resources:

Neil Cutting guest lectures on Strategic Performance Management on the University of Bath MBA Programme. This is in the Top 50 Global MBAs in “The Economist” rankings.

His day job is finance transformation executive for US-based company Jacobs. With $13bn in revenue and a talent force of more than 55,000, Jacobs provides a full spectrum of professional services including consulting, technical, scientific and project delivery for the government and private sector.

He is also a member of ICAEW’s Business Committee, which represents global business members.