It was back in June 2019 that South Gloucestershire Council joined the growing throng of local authorities pledging to become carbon neutral by 2030, 20 years ahead of the 2050 national net zero deadline.

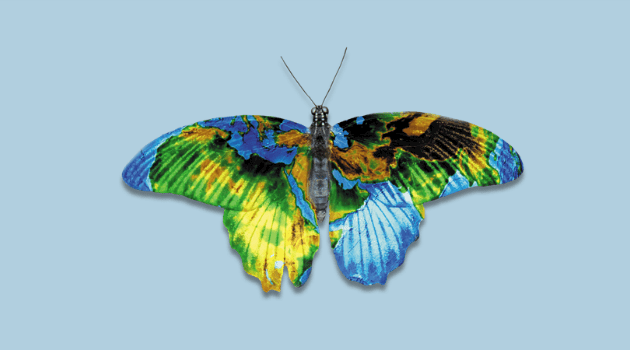

Since then, a rallying cry, prompted in no small way by the 2021 Dasgupta review, has stressed the need to better incorporate nature into conversations about risk – in particular, the need to address the decline in species and loss of biodiversity habitat.

For Barry Wyatt, the council’s Climate and Nature Emergency Manager, this is about translating the challenges of climate and nature emergencies into day-to-day local government actions. But accepting that many of the drivers of carbon neutrality are out of the council’s control, this is also about inspiring and helping others to play their part.

“Without national legislative changes, we’re unlikely to hit our 2030 deadline across South Gloucestershire,” Wyatt explains. “This is about moving beyond our statutory responsibilities and engaging with communities and businesses to get them on that pathway to nature recovery and net zero.”

Innovative solutions to climate and nature challenges

A former Director of Development Services at Stroud District Council, Wyatt admits to being battle-hardened in the legislative nuances of local government. However, that understanding has served him well in his current role, particularly when combined with an in-depth grasp of the physical environment, allowing him to come up with some innovative solutions to climate and nature challenges.

Interviewing Wyatt via Teams, his choice of photo backdrop is no coincidence. Located near the River Severn, The Wave is the UK’s largest inland surfing venue. After it struggled to source funding from commercial lenders, the council stepped in with a £2.2m loan for a solar PV farm and battery storage. “It also needed someone to act as a guarantor against European Regional Development Fund money,” Wyatt explains.

The council charged the loan at the market rate and proceeds are fed back into funding other climate activity. “It’s that understanding of place, people and businesses, understanding their challenges and seeing how we can step in and do something quite innovative for them,” he says.

Competitive funding schemes

But it’s successful bids for competitive funding schemes that have allowed South Gloucestershire to make the biggest impact. In June last year, the council had £209m worth of competitive funding from 19 different funding bodies across 55 different schemes in delivery. “We’ve been almost too successful,” Wyatt admits. Nonetheless, he says the logistics of the claim-down process across so many policies is challenging and complex – and that’s before you try to deliver the projects.

Wyatt’s team includes half a dozen project managers working across numerous competitive funding pots. “It’s not like the traditional local government services that I’ve been responsible for, which are largely core funded. It’s stop-start, transitory, competitive, fast-paced and it takes a different mindset to manage that.”

A heavy reliance on contract staff presents its own challenges, not least high churn rates. “We’re starting to get to the point where we have enough funding sources coming through that we can offer permanent contracts. But then you’ve got to make sure you’ve got a portfolio of competitive bids set out in the future to pay their salaries.” Be aware, too, that council capacity will get sucked into managing those project managers, he warns.

Using the CIL to create capacity

Core funding for Wyatt’s team to the tune of £1.5m a year comes out of the council’s Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL), a charge that can be levied by local authorities on new development in their area. “That pays for some match funding for bids, and a bit of staff time to write bids. It gave us the nudge ahead to create that initial capacity.”

Although dipping into the CIL pot was by Wyatt’s own admission a leap of faith by members, it’s a strategy that has more than paid off for South Gloucestershire. “The return is probably around four or five times that £1.5m investment.

Asked what a successful bid looks like, Wyatt reiterates the importance of a strong local understanding combined with systems knowledge. “It takes people who have been around a bit to understand where the gaps and the opportunities are and [identify the people] who have the skill, knowledge and determination to bring it together. And then you just get into a bit of a rhythm, although I do end up seeing the same paragraphs repeated in multiple bids!”

Using external consultants with sensitivity

Sort out your governance arrangements so you don’t have to get too many people to sign every sentence off, Wyatt advises. Similarly, be selective in the type of bids you target, and think about any unique local circumstances that could give you a competitive advantage. For that reason, Wyatt believes that use of external consultants, particularly those without that local knowledge, should be “applied with some sensitivity.”

South Gloucestershire worked with consultants Amey on a bid project to collect grass cuttings on verges. Cutting grass verges and leaving the cuttings increases nutrient levels, which encourages grass to grow and suppresses wildflowers. Collecting the grass reduces the nutrient value, which means the verges need to be cut less often. Meanwhile, the cuttings are mixed with the council’s food waste collections to generate biomethane using an anaerobic digester. The project is about to go live.

“Hopefully, it’s going to show not only a good carbon return, but also a good financial return. But that nugget of an idea came from within local government and brought together our understanding of highways, verge maintenance, contracting of food waste collection and anaerobic digestion to make it work. I don’t think a consultant would have necessarily been able to do that.”

Incorporating nature into decision making

With the rate of species loss increasingly apparent, engaging people on projects to mitigate the nature emergency is easier than more nebulous concepts like net zero, Wyatt believes. But a broader understanding of the council’s responsibilities and how it might be contributing to that biodiversity loss is also needed, he says.

The council uses the Cornwall climate nature decision wheel, based on the Kate Raworth Doughnut Economics model, to score any projects that go to the council with a value of £100,000+ against a series of environmental social value metrics and give them a RAG (red, amber, green) rating. “It means that decisions are not just about how much it’s going to cost.”

It’s an opportunity to open up discussions and increases the range of considerations that members have before them in informing that decision, Wyatt says. “It’s been in operation for more than a year, and we’re starting to see project managers designing their projects to take into account how they will be scored.”

Develop projects first, identify funding second

When it comes to funding projects, rather than try to shoehorn projects into funding opportunities, Wyatt’s approach is to start by developing projects before finding funding to make them happen.

The council is using a £100,000 grant from the environmental agency to identify eight green infrastructure improvement projects. Work is now under way to catalogue and attribute a monetary value to natural capital benefits they will deliver across various metrics, including air quality, physical and mental health, surface water attenuation, and carbon sequestration.

“By the end of summer, we’ll be seeking contributions to fund those projects. We’re confident that businesses will want to put their hands in their ESG pockets to contribute to them. Even though we are yet to formally launch, we have already stacked and bundled more than £300,000 towards project implementation and over £135,000 towards scheme administration.”

With 92% of the council’s emissions created indirectly from suppliers and downstream activities (known as 'scope 3' emissions), it is about to trial a new approach to carbon budgeting where suppliers of goods and services to the council will contribute towards carbon mitigation activity. “The plan is to top slice part of the contract value based on anticipated carbon emissions and put that into our own suite of mitigative and nature recovery projects. Theoretically, by 2030 we could say our Scope 3 emissions are net zero as well as our 1s and 2s.”

Meanwhile, Wyatt is eyeing up a series of abandoned coal mines in the region with a plan to use heat from them to provide decarbonised heating and cooling for up to 25,000 homes. “Look at what you’ve got within your particular patch and capitalise on those USPs to address mitigation, adaptation and nature recovery challenges.”

Supporting green transition

In its Manifesto, ICAEW sets out its vision for a renewed and resilient UK, including a net-zero investment strategy and delivery tracker.