Actions not words

Private sector demand for green investments is soaring and with it is the need for rigorous data on climate and sustainability. Companies are having to explain and evidence their green credentials, including climate related risks and opportunities, and sustainability reporting is now a hot topic for businesses of all sizes. How can they demonstrate progress on the road to carbon neutrality, and how are they managing the risks of a changing climate?

However, public bodies account for a sizable proportion of economic activity in most countries (upwards of 40% of GDP in many cases) and there can be little doubt that they will also need to play a key role in achieving net zero. Not only do governments formulate climate policy and legislation but they are also major enterprises in their own right, with large workforces, extensive property portfolios, and large fleets of vehicles, ranging from highway maintenance vehicles and police cars to tanks and naval vessels for example.

A sustainable future will require development that meets the needs of the present without compromising future generations and citizens across the world will want to assess if their governments are on or off target in meeting their climate obligations, enabling them to hold policy makers to account.

Similarly, governments will want to be able to demonstrate that they are responding to the climate emergency with sufficient urgency and to be able to justify the actions they are taking, especially if higher taxes or significant changes in the way we live our lives are required.

Having high quality, reliable and comparable information is key to being able to do that – and governments need to take the initiative and lead from the front.

Navigating the sustainability reporting landscape

The reporting landscape for sustainability and ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) is crowded and is moving at a fast pace.

Demand by investors and other stakeholders for guidance on sustainability and ESG reporting has been growing. Standards need to support the direction of capital to sustainable enterprise to ensure the functioning of capital markets. Investors and investment companies wanting to invest in businesses with green credentials need to have high quality, reliable and comparable information on which to base their decisions.

Standards based on principles of legitimacy, independence, transparency, public accountability and oversight and thorough due process are essential to obtain buy-in and trust from all stakeholders.

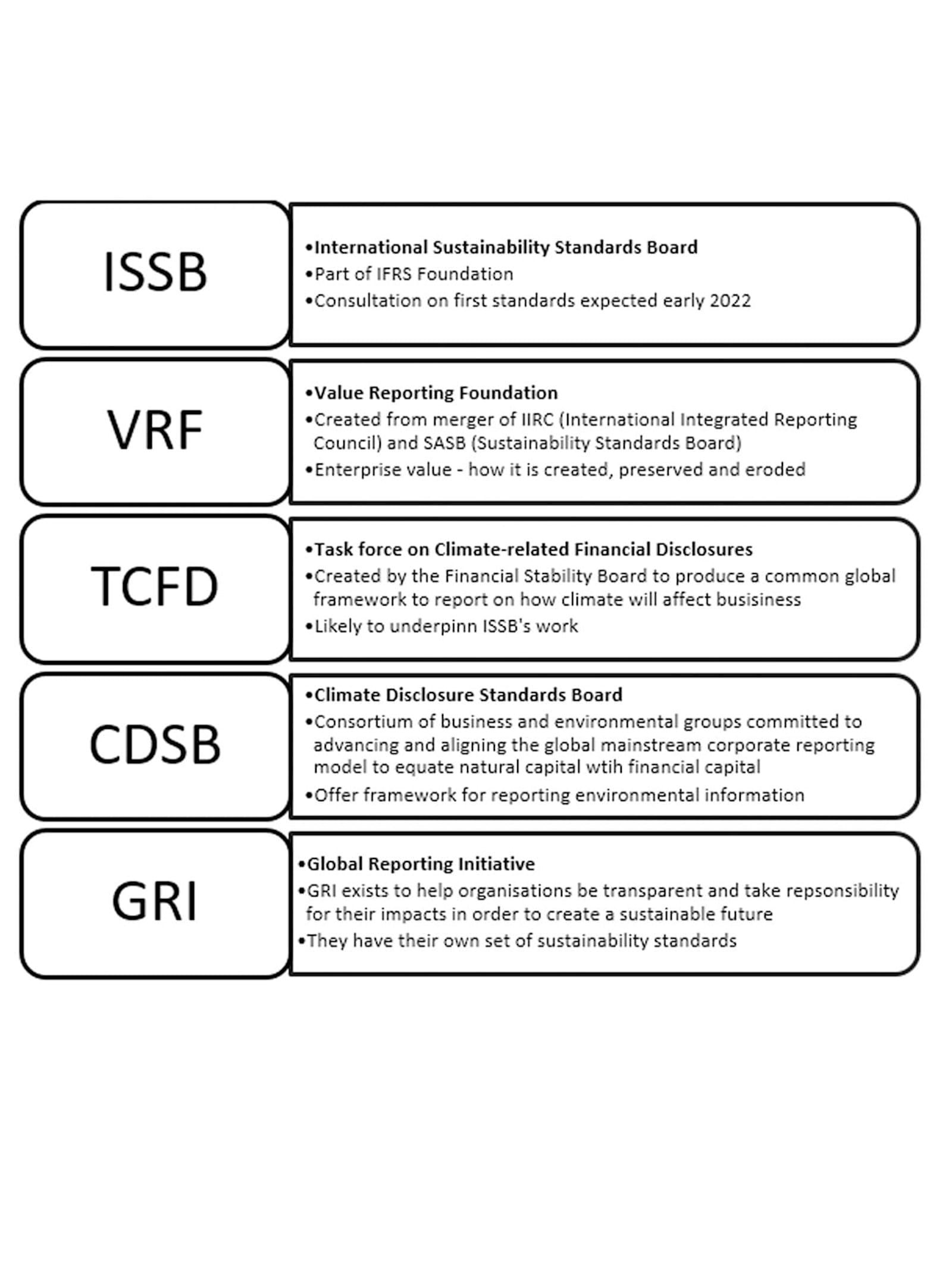

There are a number of key organisations in the field of sustainability reporting; whilst they share many characteristics and some of their work overlaps, the stakeholders that they serve vary and as a result their approaches differ, giving rise to a range of frameworks, standards and metrics. Currently, implementation of the various standards and frameworks is largely voluntary and market driven.

However, the UK government has recently announced that it will mandate disclose of climate-related risks and opportunities by Britain’s largest businesses in line with the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommendations. New legislation will require firms to implement these disclosures from April 2022, which will make the UK the first G20 country to enshrine in law mandatory TCFD-aligned requirements.

Key organisations working on sustainability, climate and/or ESG related reporting:

Calls to simplify the corporate reporting landscape have already led to the merger of the IIRC and the SASB to create the VRF and at COP26 it was announced that the VRF and the CDSB will be consolidated into the ISSB in 2022.

Where does this leave the public sector?

The plethora of reporting approaches has both advantages and disadvantages for government and public bodies in that it gives preparers the option to choose a framework that most suits their particular circumstances, or even to develop their own public sector specific reporting standards.

However, with private sector sustainability reporting likely to converge on a smaller number of internationally endorsed frameworks, public sector bodies are likely to come under pressure to adopt standards that are equal to if not more rigorous than those adopted by business.

Irrespective of the framework adopted, public entities at all levels of government risk being caught out if they do not start preparing now. The information gathering required is substantial and new internal control processes are likely to be necessary to provide assurance that progress in delivering on decarbonisation and other EDG-targets is being made as well as about the quality of the measures used to monitor and report on that progress.

Public sector sustainability reporting in the UK

The UK government committed to embed sustainability into the way it runs its operations over a decade ago. The Greening Government Commitments (GGC) were born in February 2011, setting out goals for the 22 central government departments to tackle carbon emissions and other climate related externalities.

The GGC programme is overseen by DEFRA (the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs), with policy support from BEIS (the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy) which is responsible for the greenhouse gas reduction target. The Cabinet Office and HM Treasury have key roles to play in co-ordinating and funding activity across government while the Department for Transport is key to decarbonising transport.

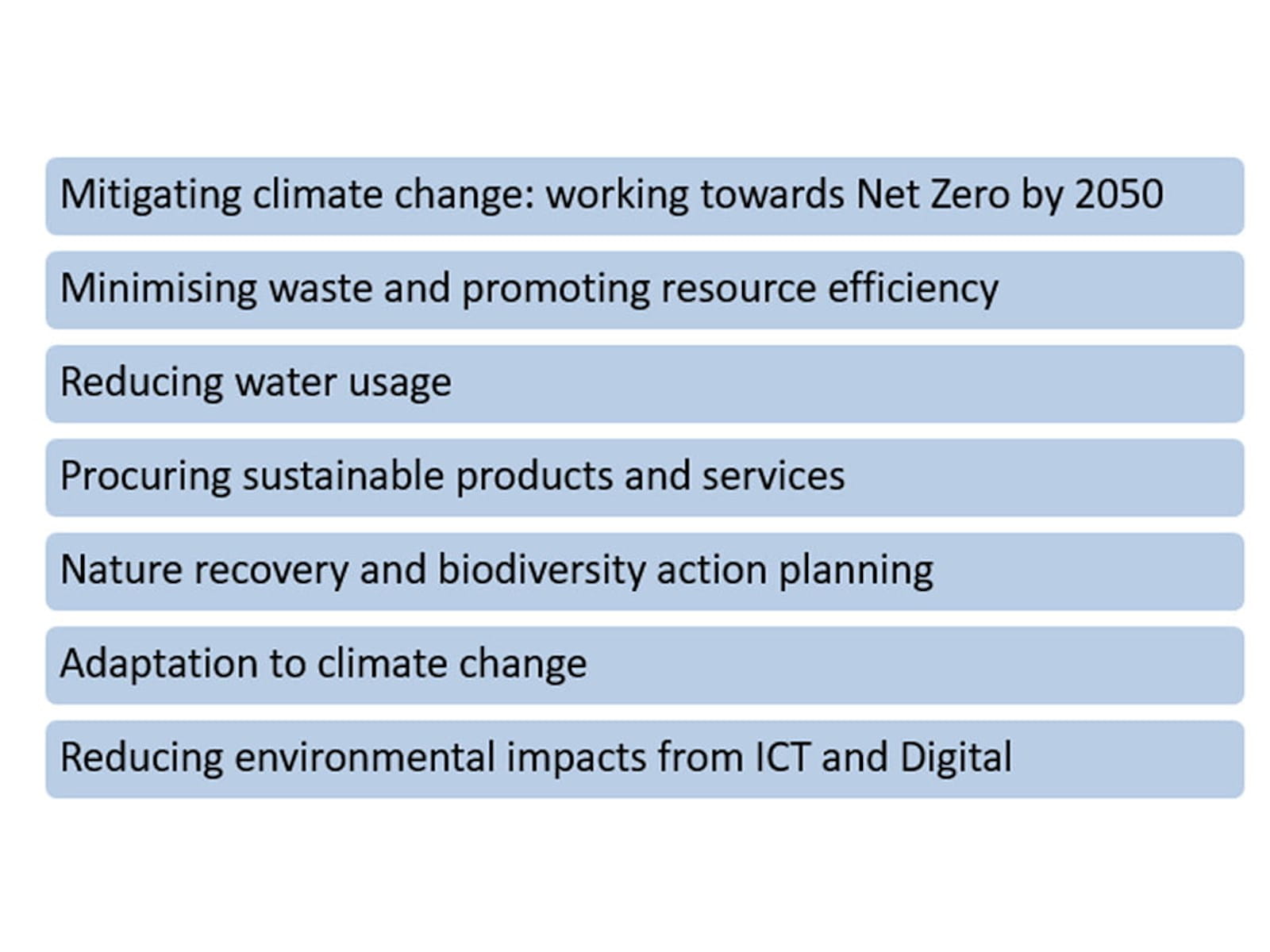

The GGCs set out the targets that central government and their agencies must meet in five-year intervals.. The first five-year period was from 2010 to 2015, followed by 2016 to 2020 and recently, the revised targets for 2021 to 2025 were published. At their heart, the targets contain ambitions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, waste, paper consumption, domestic flights, and water usage. Over time these have been refined by including nature recovery, biodiversity and climate adaption (see table below). The most recent GGCs also updated the baseline target year from 2009-2010 to 2017-2018 which should ensure departments build on progress already made.

As per the 2021 to 2025 GGC targets, departments and their agencies must evaluate their performance against each of the following commitments:

For more detail on each of the commitments above, please see appendix 1.

GGC performance

The 22 central government departments in scope of the GGC currently report on a number of metrics such as greenhouse gas emission, water consumption and recycling rates. Each department has a specific target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, as well as contributing to the aggregate central government targets in other areas.

The latest GGC annual report (the 2019-2020 report) shows that the targets for greenhouse gas emissions, domestic flights, waste sent to landfill and paper consumption were all met. Water reduction is set against internal targets and continues to decrease whilst the procurement and transparency commitments remain more difficult to measure. Departments are responsible for the quality of their own data but checks on the data and calculations are carried out on behalf of DEFRA by BRE, consultants specialising in the built environment.

There is a positive sense of achievement in the latest report, typified in how the 2020 target for greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) was already met in 2016-17 with a further ‘stretch’ target also being subsequently met. DEFRA acknowledges that progress since the baseline year of 2009-10 has benefited from the ‘low hanging fruit’ of tackling the easiest changes first. Achieving the ambitious steps necessary to achieve carbon neutrality and deliver on the government’s other targets will be much more challenging.

The new five-year commitments from 2021 to 2025 have had the base year lifted to 2017-18 and efficiency alone will not be sufficient in meeting the various targets. Greater investment and focus will be required, but it will only be over the coming decade that we will see how realistic the targets are.

Climate Change Act 2008

The GGC fit into a broader sustainability drive, in particular the 2050 target of net zero carbon emissions for the whole of the UK as set out in the Climate Change Act 2008. This will require the government sector, the private sector and households to all play their part.

The path to net zero by 2050 (which actually is 100% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions compared to 1990 levels) will be measured using a series of carbon budgets which set out five early targets for emission reductions.

The first three budget periods and their emission target status are as follows:

- 2008 to 2012 – outperformed by 1%

- 2013 to 2017 – outperformed by 14%

- 2018 to 2022 – prediction to be outperformed by around 3%

It is after the third carbon budget when things start to get interesting. Because the fourth (2023 – 2027) and fifth carbon budget (2028 – 2032) are predicted to fall short by 6% and 10% respectively 1.

Beyond GGC – what next?

UK government reporting needs to address the gaps that exist in the reporting of risks relating to climate and sustainability. The Guidance from an NAO report aimed at Audit and Risk Assurance Committees contains examples of the risks facing government departments and how they can be reported on. The report draws on the TCFD requirements to consider both physical and transition risks that arise from the changing climate as well as in getting to net zero.

Physical risk factors include weather-related events such as floods but will also increasingly include extreme heat events. Gradual rising temperatures will lead to a sea level rise and coastal changes, affecting communities and organisations in those areas as well as increasing the pressure on infrastructure such as flood defences. There are also likely to be indirect consequences including potentially higher insurance premiums or withdrawal of insurance, disruptions to supply chains, or displacement of people.

Transition risks are split into two distinct groups covering adaptation and mitigation risks:

- Adaption: the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects in order to moderate harm or exploit beneficial opportunities. The report identifies adaptation-related risks such as productivity risk (higher temperatures reduce workforce productivity) and financial and valuation risk (deteriorating effect on assets and infrastructure with costly remedies)

- Mitigation: refers to interventions to reduce emissions. Risks include policy and regulatory risks (change in legislation or tax which impact on firms and individuals) and litigation risks (loss or damage due to climate).

There is, however, a real opportunity to make the annual reports much more relevant to a wider set of stakeholders. Holding government entities to account in relation to sustainability will be very important and will only be made possible with a robust reporting framework that yields understandable, timely and comparable disclosures. We would ideally like to see ESG disclosures to be audited – not only would this provide more comfort over the accuracy of the disclosures, but it would also mitigate greenwashing.

Conclusion

Governments are currently lagging behind the private sector when it comes to ESG disclosures but given the important role this sector plays in achieving net zero, they will not be able to stay out of the spotlight for long.

The International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board (IPSASB) is due to make an official announcement on their intentions regarding sustainability in Q1 next year (March) which will be a first test to see what appetite there is to formally create public sector specific guidance. In the meantime, governments should be looking at best practice examples being generated in the private sector and determine how some of the TCFD related risks and opportunities could apply to their own entities.

The UK has made a good start with the GGCs which have already led to over ten years of experience in collecting, measuring and reporting on sustainability metrics such as greenhouse gas emissions.

We all know more needs to be done and judging by ICAEW’s public sector conference from December 2021, a lot will be done in the near future and beyond.

1. Source: House of Commons Library

Appendix 1: Greening Government Commitments 2021 to 2025

The Greening Government Commitments (GGCs) set out the actions UK government departments and their partner organisations will take to reduce their impacts on the environment in the period 2021 to 2025.

The key changes compared to 2016 to 2020 are:

- changing the target baseline year from 2009 to 2010 to 2017 to 2018, to more accurately reflect the current government estate and ensure government builds on the progress it has already achieved since 2009 to 2010

- setting more stretching targets on the core areas of emissions, water, waste and domestic flights, and introducing new measures on biodiversity, climate adaptation and food waste

- integrating the transparent reporting requirements into the core GGC targets for biodiversity and climate adaptation

- reorganising the targets into headline commitments and sub-commitments, so that departments can commit to common overall objectives, with sub-commitments which contribute to the overall aims

The GGCs are supported by specific sustainability guidance prepared by HM Treasury which assists preparers in collating and presenting this information. Whilst individual departments report on GGC in their annual report and accounts, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) who owns this process, publish specific GGC reports annually on the progress government departments are making on the targets as outlined below.

Mitigating climate change – working towards net zero by 2050

The overarching mandate is to reduce total greenhouse gas emissions including from estate and operations.

Specific targets include:

- Meet ‘Government Fleet Commitment’ – 25% of government car fleet to be ultra-low emission vehicles by 31 December 2022 and for 100% of the government car and van fleet to be fully zero emissions at the tailpipe by 31 December 2027.

- Reduce emissions from domestic business flights by at least 30%.

- Travel policies to require lower carbon options to be considered first as an alternative to each planned flight.

Minimising waste and promoting resource efficiency

Reduce overall amount of waste generated by 15% from the new baseline, 2017 to 2018.

Specific targets include:

- Reduce amount of waste going to landfill to less than 5% of overall waste.

- Increase recycled waste to at least 70% of overall waste.

- Remove consumer single use plastic from central government office estate.

- Reduce paper usage by at least 50% from the new baseline, 2017 to 2018.

Reducing water usage

Reduce water consumption by at least 8% from the new baseline, 2017 to 2018.

Specific targets include:

- Ensuring all water consumption is measured.

- Provide qualitative assessment to show what is being done to encourage the efficient use of water.

Procuring sustainable products and services

Continue to buy more sustainable and efficient products and services with the aim of achieving the best long-term, overall value for money for society.

Departments will need to embed compliance with the Government Buying Standards which prioritises value for money and streamlining procurement processes. Work to understand and reduce supply chain impacts and risks will also be undertaken.

Nature recovery – making space for thriving plants and wildlife

Departments and partner organisations with the greatest potential to improve biodiversity should develop and deliver Nature Recovery Plans for their land, estates, development, and operations.

By developing and delivering a Nature Recovery Plan, a department or partner organisation will show that it has:

- identified and taken opportunities to integrate biodiversity considerations into all relevant service areas and functions, and ensured that biodiversity is protected and enhanced in line with current statutory obligations at a minimum.

- taken action to deploy nature-based solutions and raise awareness of staff and managers about biodiversity issues.

- Specific commitments where relevant include tree planting, protecting and enhancing peatland, pollinator-friendly habitat and land as a contribution to Nature Recovery Network – which is a government commitment to protect 30% of land by 2030.

Adapting to climate change

The overarching task is to develop an organisational Climate Change Adaptation Risk Assessment and develop a plan to respond to the risks identified.

Departments should establish clear lines of accountability for climate adaptation in estates and operations and provide a summary of how they are developing and implementing a climate change Adaptation Strategy in their annual reports and accounts.

Reducing environmental impacts from Information Communication Technology and digital

Departments should report on the adoption of the Greening Government: ICT and Digital Service Strategy. In summary, this will include delivering an annual ICT and digital footprint, waste and best practice data for each department and their partner organisations.