The ability to not only survive but thrive in uncertain conditions is increasingly the understanding of what is meant by organisational resilience1.

While we have all become experts at living in times of uncertainty, Boards of directors are faced with the accountability of attempting to ensure that their organisations are aware of and adequately managing potential threats and opportunities that may or may not materialise.

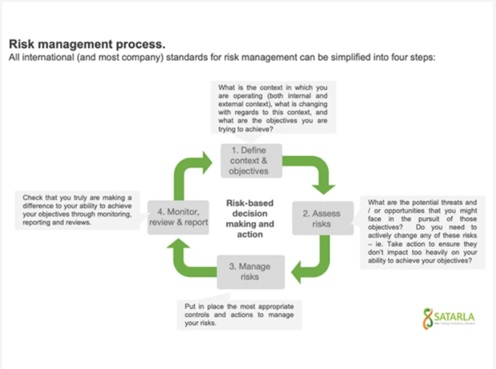

The primary tool that a Board has for gaining insight to an organisation’s ability to predict and proactively manage its future is risk management. Often a tick box exercise, risk management rarely provides the insight needed for the Board to carry out their job of challenging the organisation. So, what should risk management look like within an organisation and what should the Board of directors be doing with this information to support their organisations in becoming more resilient?

1) Accept that risk management will mean something different to every discipline and culture and embrace this diversity. For some it is about trying to stop bad things from happening, such as people being hurt or not complying with a regulation; for others it is about spotting trends in the market before anyone else sees them and creating opportunity. Rather than trying to force everyone into the same way of thinking about risks, the organisation’s approach to risk management should be flexible enough to allow individuals to share their perspectives. This allows all risks that may affect the organisation to be acknowledged.

What does this mean for the Board? Expect to see a very simple form of Enterprise Risk Management that allows for risks to be collated across the organisation. Ideally the Chief Risk Officer should be the voice of conscience working with the CEO and Head of Strategy, constantly refining the direction of the organisation based on their understanding of what the future might hold. Board members should always be welcomed for their input to this process and suggestions for new or evolving risks.

2) Risks exist in a network with one person’s risk often being someone else’s cause or consequence. Risks don’t exist in isolation and rather are interconnected. Ideally this network of risk is dynamic enough to have new or emerging risks added, only to evolve or merge into something a little different as increased understanding of that risk is gained.

What does this mean for the Board? Expect to see risks evolve when presented to you. Challenge them to ascertain what the cascade impact of that risk might be and where in that cascade it should be best managed. Try and move the organisation away from impact v likelihood graphs towards a prioritisation tool such as impact v action. The use of likelihood often leads to game play and a distraction from the most important risks to the resilience of the organisation.

3) Risk appetite and tolerance refers to “how much risk is too much risk” and then sharing these tipping points throughout the organisation. Challenging the organisation to ensure they know exactly what the capacity is for the organisation not just in monetary terms but also regarding e.g. sustainability is very useful, not least for those deeper in the organisation who want to know just how much imagination they can use when achieving the company’s strategy. Ultimately it is this that builds the “risk culture”. However, once these lines are drawn, they need to be constantly reviewed, specifically because they will change giving changing contexts and requirements of the organisation to navigate uncertain conditions.

What does this mean for the Board? Don’t settle for a narrative form of risk appetite that just refers to the organisation being “averse” to taking risk. Push for more detail by asking for examples of what this really means2. When these tipping points are reached, challenge the organisation on what they are doing about those risks and ask what needs to change in order for the organisation to survive.

4) Risk management is the mechanism through which the purpose, virtues and strategy of an organisation is constantly challenged and refined. At its simplest, enterprise-risk management should allow anyone within an organisation to ask: Given the context in which I’m operating and how it is changing, and the risks I face, and my ability to manage them, is it possible to achieve my objectives? If the answer is “yes” – great, everything is in balance. If the answer is “no”, there are only two options: a) pump more time, money and effort into managing that risk; or b) change the objectives (see Fig. 1).

What does this mean for the Board? Be open to challenging the organisation to change its strategy if risks are unable to be managed3. The inability to manage risks is often an early warning signal of times of stress on the organisation.

In conclusion, risk management should enable an organisation to proactively recognise and manage potential threats and opportunities to its success. To do this, it needs to be inclusive, integrated, flexible and transparent. Board members need to use the information to challenge leadership as to their level of resilience.

*The views expressed are the author’s and not ICAEW

1IRM resilience guideline

2Operationalising Risk Appetite

3Simple 4 x step risk management process