The switch from the internal combustion engine to EVs is a revolution for auto manufacturers and already stressed supply chains. What will it mean for investment and M&A in the sector? Jason Sinclair reports.

The automotive industry has been something of a hot political potato this year: the UK government is attempting to navigate a new reality; there are increasing green priorities, changing consumer behaviour; and supply chains are ever more complicated, with many carmakers having operations that straddle the globe.

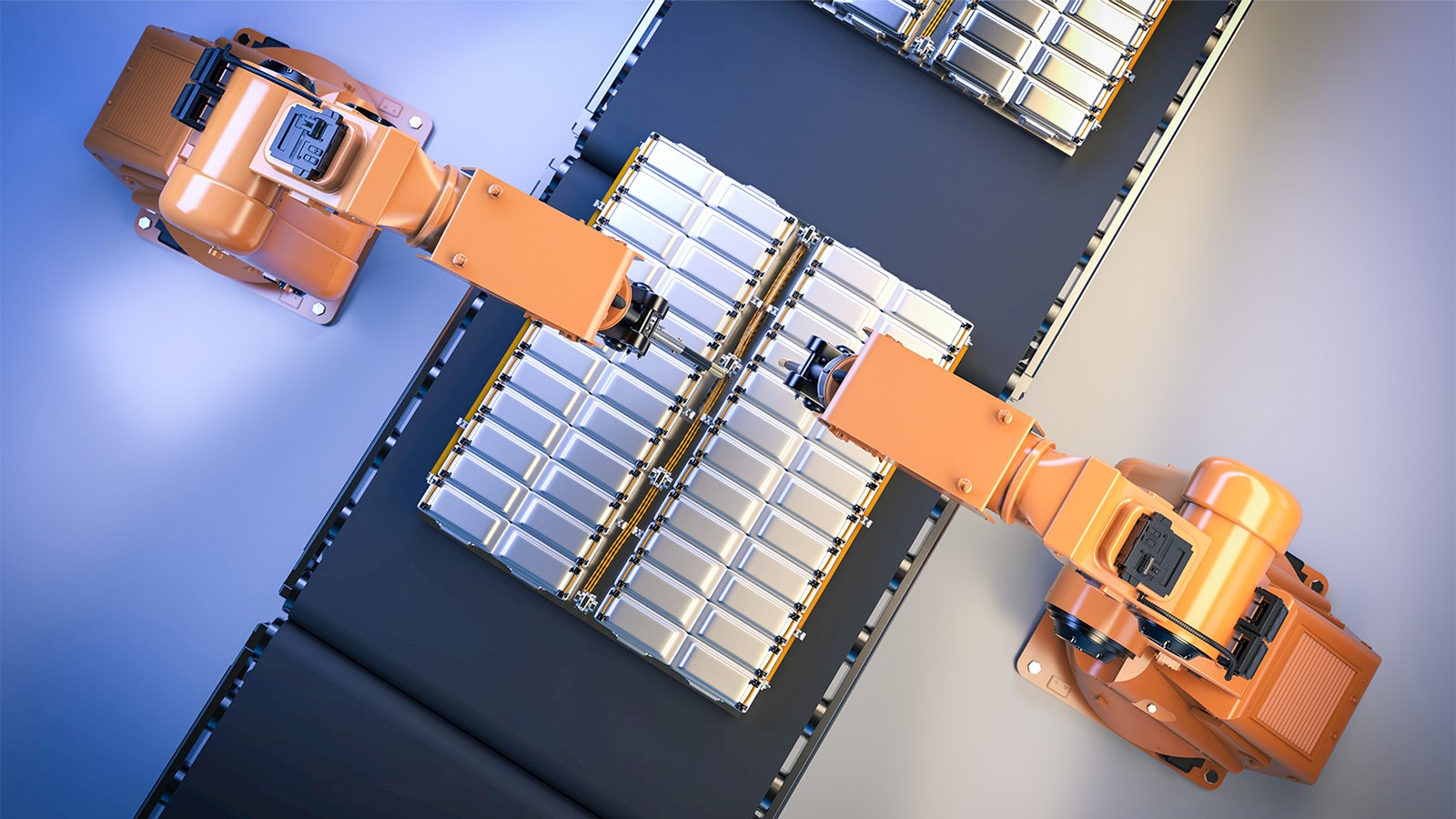

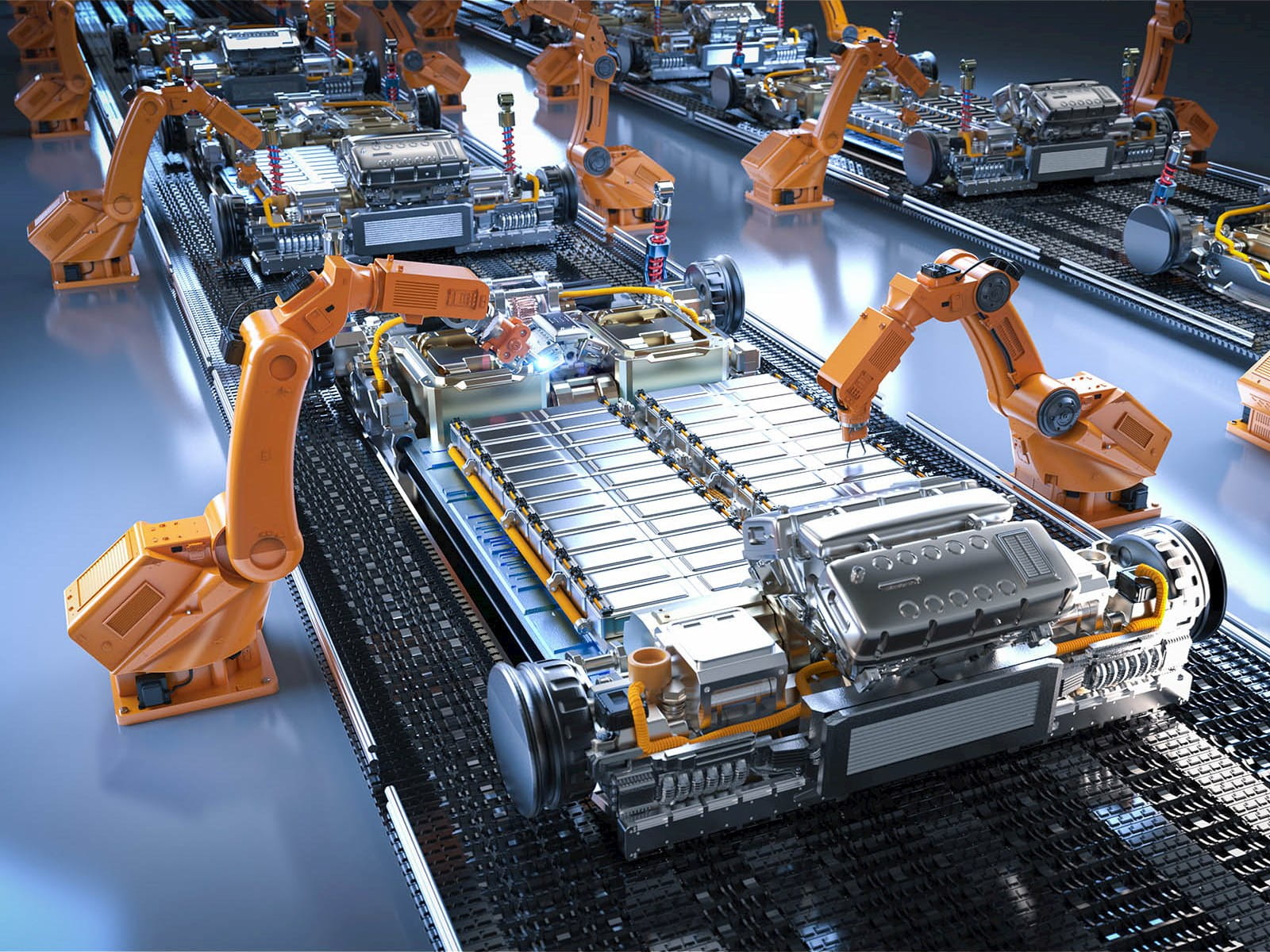

The conundrum becomes more complex and important to solve when you realise that according to the latest figures, from 2023, 780,000 people work in the auto industry across the UK. Some 182,000 of those are employed directly by 25 auto manufacturers and the rest by 2,500 parts-making suppliers, building more than 70 vehicle models. Those models will transition to electric in the next seven years. By 2030 all new cars and vans sold in the UK must be electric. The focus will undoubtedly be on the sourcing of batteries, the roll-out of a nationwide charging point network and new ways of manufacturing, servicing and financing. The industry is replacing a process that for 130 years has been based on the internal combustion engine.

“Every country in the world is desperate for an automotive industry,” says Mike Hawes, chief executive of the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT). “In the UK, we want to retain what we have, but also create the conditions for the industry to grow and attract additional investment because of the massive contribution to local communities, with the jobs that manufacturers create and the multipliers, as well as the contribution to GDP and export. You jeopardise all those benefits at your peril.”

Financing a car

Consumer behaviour has switched from buying cars outright to increasing use of short-term leases and subscription models, meaning new models of financing – and new companies – are coming to market. “You don’t necessarily need EVs for some of those new ways of vehicle funding to emerge,” says Maria Bengtsson, “but it has coincided.”

Deloitte’s annual Global Automotive Consumer Study found a clear trend towards leasing cars, says Richard Hopkins-Burton. “The more recent trend is shorter and shorter lease periods as people just don’t want to be tied to a particular brand, or even a particular generation of technology because charge rates and battery range and performance advance at such a rapid pace with each new model that is coming on to the market. And at the moment, second-hand valuations are really volatile, so consumers just don’t want to be locked in – they value flexibility and the ability to jump in one car, jump in another and not be tied down to something.

“That’s creating lots of opportunities around new business models, such as much more flexible leasing, subscription services and car sharing clubs – which can attract really good margins compared to traditional leasing – with consumers effectively willing to pay the flexibility premium. Manufacturers and leasing companies I’ve talked to are all looking at or have already launched new business models along those lines.”

But the industry is facing the greatest period of change since the Model T first came off Ford’s game-changing Detroit assembly lines more than a century ago. Within the industry, talk is about the ‘CASE’ trends – connected, autonomous, shared, electric – that are changing the market. “The CASE trends are clearly the opposite of the traditional auto business model, where cars are privately purchased as a product,” says Richard Hopkins-Burton, head of automotive M&A transaction services at Deloitte. “Previously, they were very much hardware-focused, human-driven and powered by the internal combustion engine, so the disruption that’s happening in the change from the old business model to the future business model is fundamental.”

Tech on wheels

This change means that the auto market can be looked at as “the IoT [Internet of Things] market on wheels”, according to EY-Parthenon partner Charlie Simpson, whose brief includes advanced manufacturing, mobility and energy transition – three of the key elements of the modern auto industry. His “IoT on wheels” definition means the market could be prone to “fairly heavy regulation” in what Simpson calls “a pretty lively space” but, he says, “from an investor mobility point of view, the business model around tech and connected data is actually an easier investor story because it’s a derivation of the data and the telecommunications business model, albeit with wheels. So we’re seeing it being investable and the maturity curve of connected vehicles appears likely to mature more quickly at scale.”

The ‘investability’ is important in an industry whose outgoings have to account for two different priorities: the vehicles of today and those of the future. “We’ve got this very interesting double play where there’s going to be a run-down of the legacy internal combustion engine business over the next 15 to 20 years. At the same time, you’ve got the ramping up of a very differently shaped business, which is more about green energy, connectivity and services,” Simpson says.

“We’ve got this transitional play, where you’re seeing both old world and new world colliding, throwing up some really interesting challenges for legacy players and giving an opportunity for new players coming in with less of that legacy asset base.”

Hopkins-Burton warns: “Current financial performance is a red herring to some extent, because auto companies are having to navigate a transition period. They’re having to continue to invest in and support their current existing product portfolio, which is their current source of profits. But at the same time, they have to invest in the future business model and future technologies that will pay back in the long term. Effectively, you have duplicate costs and duplicate investment, and that is causing some short-term pain.”

Much of the M&A Hopkins-Burton has been involved in centres on clients having identified a gap in their portfolio of technologies, capabilities or products and gone out into the market to plug that gap with M&A: “For example, in the supply chain, companies must continue to invest in producing and supplying parts for internal combustion engines, but simultaneously invest in a new product portfolio related to electric vehicles, whether through internal R&D investment or through buying new companies. They need to do both.”

Big players

The current major manufacturers are “best placed to adapt their business model to the future market and thrive”, says Hopkins-Burton. “Of course, that means a lot of change, but they have the capital, the expertise and the experience of what it takes to build and sell cars and set up a supply chain in order to achieve that.”

For smaller companies in the sector, partnerships and joint ventures are providing a path to growth. And, says EY’s electric vehicle lead in the UK, Maria Bengtsson: “There’s a lot of these small, nimble, innovative companies really driving technology and innovation forward.

“We work with smaller players to see how they need to partner to reach critical scale, which is where they need to be. There are often limits to operating as a very small innovator on your own because many or all of your big customers will likely want to engage with a bigger entity and access a more comprehensive solution, so the challenge for the smaller players is what role they can play in the ecosystem and who they can partner with. Meanwhile, the bigger players need to find the right solutions from these smaller suppliers, so connections are being made. We see a lot of transactions as well, but partnerships are a route many companies are taking.”

Cara Haffey is UK manufacturing and automotive lead at PwC. She says: “Corporate players are focused on acquisitions to gain access to new technologies and service capabilities, or to create scale efficiencies through consolidation. A continued focus on building greater resilience into their supply chains is also keeping corporate M&A activity at a stable level.”

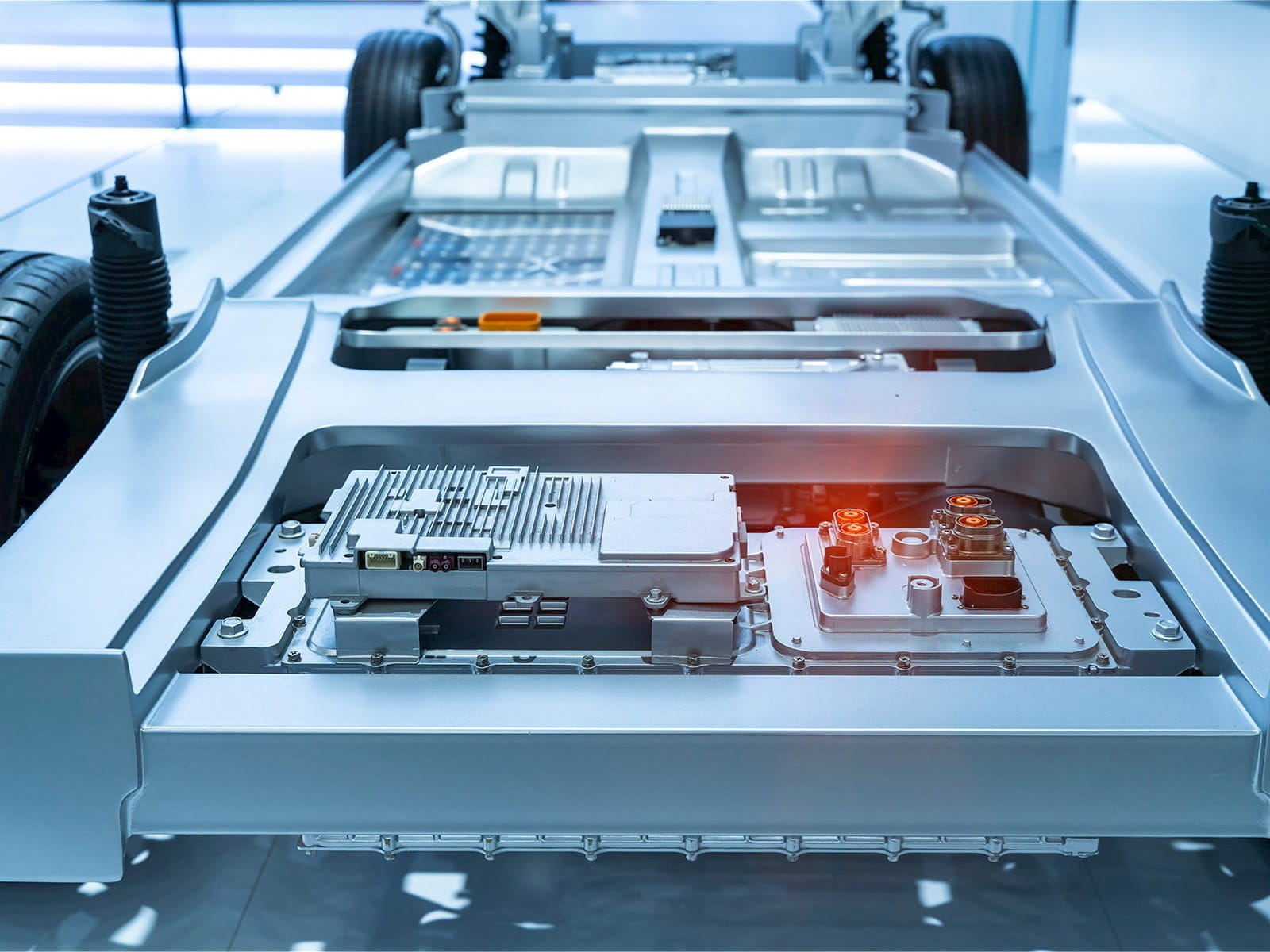

Haffey also sees the trend towards more digitised and software-powered vehicles fuelling further investment in new technologies: “The availability of software engineers will become a key factor, influencing the pace of digital transformation in the sector, and talent will subsequently drive the strategic rationale for many acquisitions.” This, she says, will include ‘acqui-hire’ plays, when one company acquires another to gain skilled workforces, with talent driving the strategic rationale for many deals. “About 100 million lines of code underpin the operation of a modern car,” she points out, “compared to a passenger jet running 14 million lines of code, or a fighter jet, with about 25 million.”

As expensive as chips

If auto manufacture is, as EY’s Charlie Simpson says, “the IoT on wheels” and his colleague, EY automotive leader in the UK David Borland, looks to “key changes around digitalisation of the vehicle and the customer experience”, it points to the auto industry being treated as a road-going offshoot of the tech sector. This has consequences for valuations, and for regulations – particularly bearing in mind protectionist safeguards in the US and their consequences for supply chains.

It also means tech companies – such as chip designer ARM – are moving into the automotive market and gaining profits from the chip-heavy moving computers. “A high-end car is approaching one of the most complex pieces of software you can have in the world at the moment,” ARM’s VP of Automotive, Dennis Laudick, told the Financial Times. “It’s basically a data centre on wheels.”

It is not just about being green – it is about an all-round tech-fuelled driving experience. The UK-based, SoftBank-owned company is facing competition from other tech giants such as Intel and Synopsys to assemble the most powerful intellectual property in the evolving industry, which is no longer dedicated to manufacturing boxes of ‘hardware’. Those 100 million lines of code in a modern car’s software? This is expected to rise to 500 million by the end of the decade.

Hawes accentuates this as a positive for the UK: “From an investment perspective, we have a very productive workforce with good links to academia. And we have a well-established automotive industry, with Rolls-Royce, Bentley, Jaguar Land Rover, Aston Martin, McLaren and so on, as well as German and Japanese brands such as BMW and Toyota, and there are good ecosystems around that.”

From there, however, the picture becomes less positive, as the industrial policies of the US, EU and China mean the UK risks squandering that competitive advantage. “Are we competitive enough to attract that inward investment in new electric vehicles – and particularly in batteries?” Hawes asks. “When you look at the global context, whether it’s the Inflation Reduction Act in the US or the COVID-19 recovery plan in the EU, big money is being put on the table to reshore manufacturing to those respective markets – huge money in the case of the US. What are we doing in the UK? We’re still waiting for a response.”

Lithium rush

In November Trafigura-backed Green Lithium announced it was building a £600m lithium refinery in Teesside, which is of course welcome. Altilium Metals is also building a lithium recycling centre in the region. After the shambles of Britishvolt, there is hope that a gigafactory for Tata and Jaguar Land Rover in Somerset, currently at the ‘advanced talks’ stage, will create 9,000 jobs and bring supply chains closer to home. “The UK should be in the vanguard,” says Hawes. “We’re a relatively affluent market on a global scale. We like new technologies, we’re relatively small and densely populated, so it should lend itself to infrastructure.”

But there are questions as to whether the charging infrastructure for the coming wave of EVs has been built to the scale required. “We’ve seen a lot of capital deployed into the charging network over the past four or five years,” says EY’s Simpson. “We have worked on quite a few of the deals. However, one of the key issues emerging is backlog of projects around connectivity and currently there doesn’t appear to be a joined-up perspective on this. Have we got enough yet? No. Do we have good volumes in the pipeline? Yes. It’s going to get fixed, but it’s likely to be challenging for the next five or six years.”

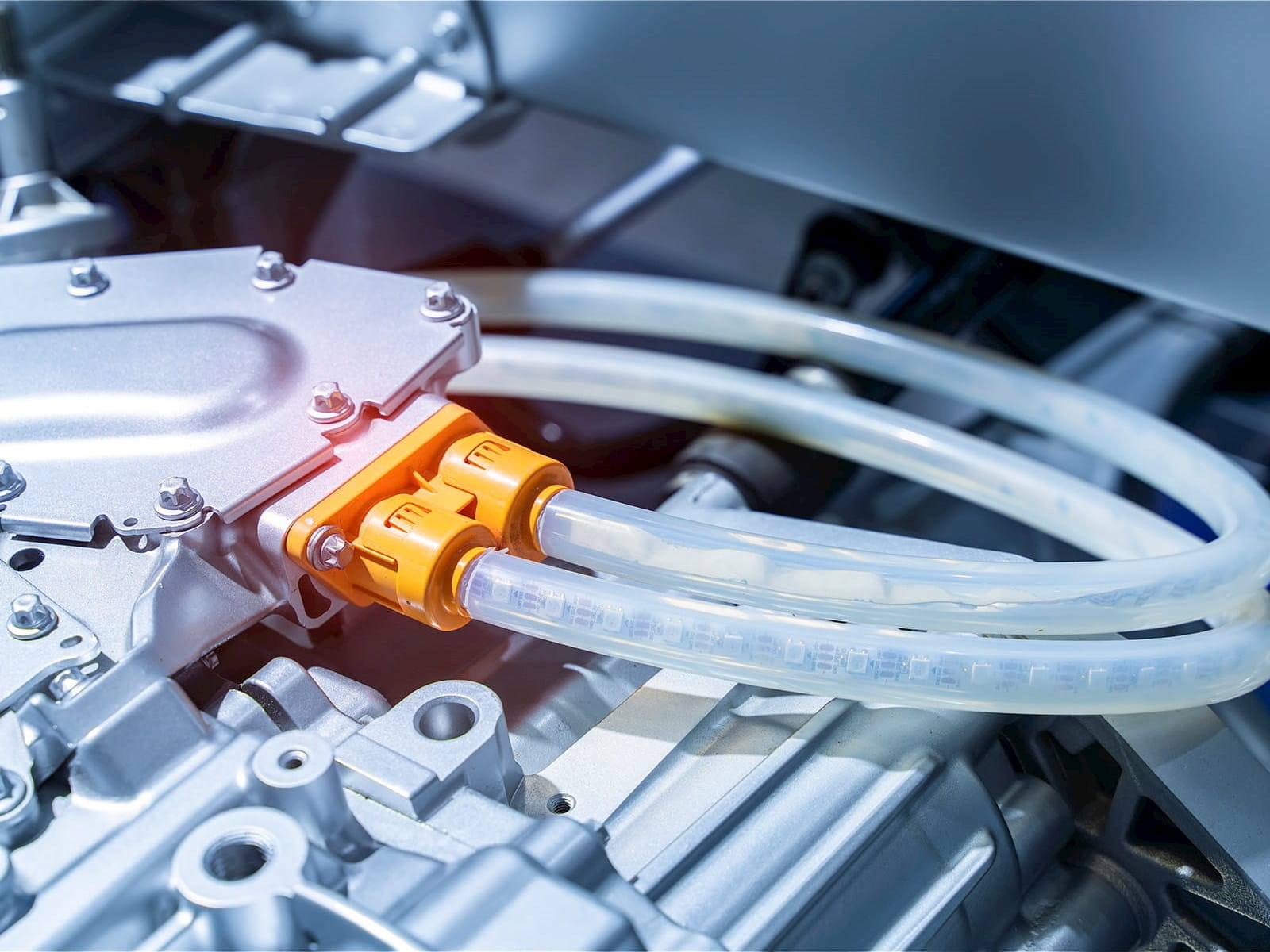

On supply chain issues, Bengtsson says the battery gigafactories being built in Europe and, potentially, the UK are “securing a part of the supply chain going backwards, but there’s only so far back in the chain you can go and most of the materials coming into those factories are still coming from outside Europe”.

The lithium ‘gold rush’ that has been played out in China and the US, as well as resource-rich developing states such as Bolivia, is seeing activity in Germany and Slovenia to secure access to the rare earth metal. “It’s suddenly a viable proposition”, says Bengtsson. Haffey expects this to lead to more cross-sector M&A where “automotive companies are buying into or directly securing product offtake from the miners of critical minerals used in battery production. The original equipment manufacturers are not leaving it to the suppliers to secure these materials.”

The onshoring or ‘nearshoring’ of critical components will build more resilience into supply chains, thinks Haffey. And, says Deloitte’s Hopkins-Burton: “You’ve got the likes of Tesla looking at buying a Canadian battery metals miner, for example, going right into the raw materials and securing the supply chain that way. You’ve got Volvo looking at lithium miners and processors and acquiring equity stakes. That’s the ultimate example of going right into the vertical integration to secure the supply chain. Ultimately, batteries are heavy and they explode. So shipping them densely for long distances is not efficient. Wherever you make cars, it’s probably sensible to have battery factories as well, in the long term.”

Could this leave the UK out in the cold? “The automotive sector is now being heavily impacted by broader geopolitics,” says Simpson. “To understand what’s going on, you can’t just think about what’s happening in that one sector. It’s increasingly influenced by the convergence of auto and transport meets financial services meets technology meets energy meets future retail. That’s really the landscape and it won’t look much like traditional automotive over the next 20 years.”

Of course lithium is not the only way. Toyota and Hyundai are investing heavily in hydrogen technology, which is potentially a far better green solution for larger vehicles.

The challenge for the UK, with the backdrop of its 2040 net zero targets, is not just expansion of EV charging networks. The UK needs to ensure its electricity grid can cope with EV charging demand, fast charging at economical prices, and taking into account peak demand levels.

Power politics

Simpson continues: “The other overlay is the geopolitics around this, which is more tied to energy and technology. We’re seeing very clearly an influence from the likes of China, and of course North America, which has been accelerated by the Inflation Reduction Act. And you’re starting to see the European response, while you also see India powering up through the likes of Tata Motors. These four big geopolitical players are influencing a lot of what we’re seeing while the UK is in a more challenging position.

“Clearly,” he says, “the UK has some great inherent strengths around the scale and innovation of the market, but the reality is that, particularly with this geographic polarisation, being outside one of the big blocks could cause increasing challenges. The convergence of Brexit and some of the fundamental financials leaves the UK in a pretty difficult position and the lack of UK industrial policy to tackle issues that were known about five or six years ago is really starting to have an impact.”